Babesiosis is a rare infectious disease caused by unicellular intraerythrocytic protozoan parasite belonging to the Babesia family.1

Most human cases of babesiosis are caused by B. microti, which is transmitted by the Ixodes scapularis ticks. The first documented case of babesiosis in the United States occurred in California in 1966; however, the causative species was never determined. It was not until 1969 that the first documented case of babesiosis caused B. microti was recorded on Nantucket Island, Massachusetts.2 Since 1966, the number of babesiosis cases in the United States has been increasing. Therefore, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) started to conduct surveillance for babesiosis in the United States in 2011.2 The data shows the number of documented cases of babesiosis has been steadily increasing, from roughly 1,100 cases in 2011 to approximately 2,400 in 2019. The highest incidence of these cases is found in the northeast region of the U.S.

Babesiosis can present with a varied clinical presentation, which can make it difficult to diagnose. Most people remain asymptomatic or experience mild symptoms. On the other hand, there are documented cases where the intraerythrocytic parasite can lead to severe complications. These complications are often seen in patients with certain risk factors, such as immunocompromised immune system, asplenic individuals, or the elderly. Symptoms develop over 1-4 weeks after exposure to the parasite.1 Early signs of an infection present with fever, malaise, joint paints, decreased appetite, sweats.1

Case

The patient is a 73-year-old Caucasian male who resides in New York with a past medical history of atrial fibrillation (on apixaban for anticoagulation) who presented to the emergency department with intermittent palpitations of 1 week in duration. Patient reports that his atrial fibrillation is under control and has been able to maintain normal sinus rhythm prior to the onset of palpitations. He associates the palpitations with mild-to-moderate fatigue and decreased appetite that have left him unable to complete his activities of normal living. He denied any recent travel and sick contacts.

Upon further questioning, the patient reported that he spends a lot of time in his garden, which also contains a small fishpond. He mentioned that he has been bitten by ticks multiple times in the past, but does not recall any known recent tick bites.

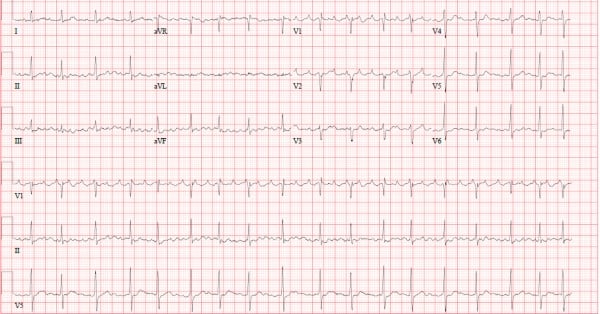

At presentation, the patient was febrile to 100.4F with an elevated heart rate of 104 bpm. His heart rate was noted to be irregularly irregular. EKG showed atrial flutter with a variable block (Figure 1).

Labs, two sets of blood cultures, chest X-ray, tick panel, malaria/babesia smear, and urinalysis were obtained since the vague symptoms did not localize to a specific source. Patient was given lactated ringers upon initial exam. Antibiotics were delayed until a source was identified.

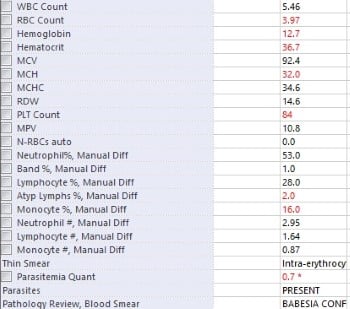

Initial labs showed evidence of acute kidney injury, elevated B type Natriuretic Peptide (BNP), mild elevation in total bilirubin, thrombocytopenia, mild anemia (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Chest X-ray did not reveal any acute cardiopulmonary processes.

In the end, the patient’s parasite panel resulted positive for parasites in the blood. Follow-up pathology smear confirmed the presence of B. microti in the patient’s bloodstream. Upon re-assessment, the patient remained intermittently tachycardic, but the patient noted clinical improvement after intravenous fluid administration. The patient was notified of these results and was promptly started on antibiotic regimen of azithromycin 500 mg and atovaquone 750 mg. The patient was referred for follow-up with infectious disease and cardiology.

The documentation from the outpatient infectious disease evaluation indicated improvement in symptoms after the course of antibiotics. Repeat EKG from cardiology outpatient visit shows normal sinus rhythm.

Discussion

B. microti is an apicomplexan parasite that infects the red blood cells of its human hosts. It belongs to the family Babesiidae. The main vector for B. microti is the Ixodes scapularis tick, which is seen prominently in the northeastern United States. The main reservoirs include the white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus), short-tailed shrews (Blarina brevicauda), and eastern chipmunks (Tamias striatus).

The clinical presentation of babesiosis is varied and depends on the patient and his/her comorbidities.1 The presentation ranges from asymptomatic infection to severe illness with multiple complications. Early stages of the infection can include generalized systemic symptoms such as fever, lethargy, decreased appetite, sweats, headaches. As the disease progresses, one could start to see hepatosplenomegaly, impaired renal function, jaundice, and hematologic manifestations.1

The hematologic manifestations of anemia and thrombocytopenia are well-documented in cases of babesiosis. The anemia is progressive and worsens with continued untreated infection as the parasite lyses red blood cells (RBC) upon exiting them.3 Otsuka et. al studied babesiosis within dogs. The research showed that RBCs with the parasite had higher production of superoxide, resulting in increased lipid peroxidation and cell membrane rupture causing the eventual cell death.3 There also may be a component of immune thrombocytopenia as well, but no definitive evidence exists to date.

On the other hand, thrombocytopenia relates to the hypersplenism that leads to increased platelet sequestration and destruction. In more severe cases, the thrombocytopenia can be secondary to disseminated intravascular coagulation.3 Early antibiotic administration helps to reduce the risk of more severe hematologic and multi-system complications.

Diagnosis & Management

The diagnosis of babesiosis is made upon history of exposure to tick bites in areas known to have increased risk of babesiosis along with pathognomonic lab results. Physical examination is limited, as most patients have a vague presentation. The diagnosis is ultimately made with analysis of thin smear of peripheral blood using Giemsa or Wright staining. Ring forms are commonly seen within RBCs. Tetrad formations, otherwise known as Maltese crosses, are occasionally seen. PCR testing and serology testing with indirect immunofluorescent antibody testing can be done at reference laboratories and can help confirm the diagnosis.

As per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, symptomatic patients should be treated with atovaquone 750 mg orally twice daily for 7-10 days and azithromycin 500 mg orally for 7-10 days. Alternative regimen includes clindamycin 600 mg orally three times daily for 7-10 days with quinidine 650 mg orally three times daily for 7-10 days. The latter is reserved for severe babesiosis infections.

The multi-organ involvement of babesiosis is well-documented; however, babesiosis affecting the cardiovascular system is not well-documented and appears seemingly rare. Two case reports of cardiac manifestations related to babesiosis based on the literature search are listed in Table 1. There have been no documented case reports of babesiosis triggering tachy-dysrhythmias.

The pathophysiology on how this unicellular intraerythrocytic protozoan causes atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter is unclear, thus warranting further investigation. With case reports showing the connection of myocarditis and CHF related to babesiosis, there could be a potential pathophysiological mechanism for underlying cardiac manifestations.

Lyme Disease is a tick-borne spirochetal infection that is well known in the northeastern United States and has many well-documented cases of causing reversible heart block in affected individuals. Perhaps babesiosis affects the electrical conduction system of the heart in a similar manner, but causes elevated heart rates and arrhythmias. As mentioned, more investigation is warranted before any conclusions can be made.

As the number of documented babesiosis cases rises, this case emergency physicians another rare cause of tachy-dysrhythmias. Prevention of tick bites by avoidance and immediate removal of ticks remains the best approach for prevention of the illness. Ticks require at least 36-48 hours of attachment to transmit the disease. Thus, immediate removal is the best way to prevent babesiosis.

Table 1: Case reports on cardiac manifestations due to babesiosis

|

Babesiosis associated myocarditis |

An 83-year-old male with coronary artery disease (CAD) presents to the hospital with complaints of chest pain and pyrexia. Labs were significant for thrombocytopenia, transaminitis, and elevated troponin. EKG showed ST depressions globally. Tick serology was positive for babesiosis. |

|

Case of Babesiosis in the South Bronx |

A 66-year-old male with HTN, DM, HLD, CKD presented to the ED with CHF exacerbation that was triggered by his underlying babesiosis. |

References

- NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Babesiosis. 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Babesiosis surveillance - United States, 2011–2015. 2019.

- Akel T, Mobarakai N. Hematologic manifestations of babesiosis. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2017;16(1):6.

- Yabsley MJ, Shock BC. Natural history of Zoonotic Babesia: Role of wildlife reservoirs. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. 2012;22(2):18-31.