Traumatic splenic injury and hemorrhage is a diagnosis familiar to most emergency physicians. However, a condition that some may not be familiar with is atraumatic splenic rupture.

Although an uncommon diagnosis, atraumatic splenic rupture is a critical diagnosis that should be included on the differential for abdominal pain, especially in the setting of associated undifferentiated hypotension, as it can quickly lead to instability and life-threatening intra-abdominal hemorrhage.

Case

A 52-year-old female presented to the emergency department late one evening by ambulance with complaints of sudden onset, intense, left-sided abdominal pain. On arrival, EMS reported that they could not obtain a blood pressure but that she was tachycardic, diaphoretic, pale, and almost passed out while they were helping her to the stretcher. On our initial evaluation, her vitals were: heart rate 130 bpm, systolic blood pressure 60 mmHg with an undetectable diastolic pressure, respiratory rate 25 breaths per minute, temperature 97.4F, and SpO2 96% on room air. She was in significant distress and demonstrated notable pallor, significant abdominal tenderness with guarding, rebound, and distention, as well as a fluctuating level of alertness.

A brief history obtained from the patient revealed that the pain had woken her from sleep, was primarily in the left upper quadrant, and was associated with nausea, weakness, and an episode of near syncope. There were no reports of trauma to the abdomen, and she had never experienced symptoms like this before. She denied fever, chills, or recent illness. She provided the additional pertinent information that she was currently undergoing workup of a large pelvic mass by gynecologic oncology in the outpatient setting, but otherwise she did not have any significant past medical or surgical history.

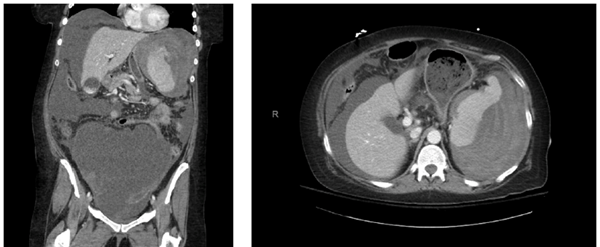

Large bore IV access was immediately established, and an initial liter of normal saline was given rapidly via pressure bag, with minimal improvement in her vitals and mentation. Point of care ultrasound was performed to identify a potential source of the hypotension and abdominal pain, which revealed a significant amount of free fluid within the abdomen. This was presumed to be hemoperitoneum of unknown etiology, but initially thought to be potential hemorrhage from the aforementioned pelvic mass. Upon identification of this free fluid, emergency release blood was requested, as well as an emergent surgical consult. The patient was stabilized after receiving the initial fluid bolus and 2 units of emergency release blood. She was then taken to the CT scanner, where she was found to have a ruptured subcapsular splenic hematoma with active extravasation (Image 1 and 2). The pelvis mass was again identified and was unchanged from prior imaging. Additionally, workup in the ED showed a BMP within normal limits, normal PT/INR, EKG with sinus tachycardia, and a negative UA and pregnancy test. CBC revealed a leukocytosis of 19.4, Hgb 6.5, Hct 21.5, and platelets 476.

| FIGURE 1. Coronal CT scan demonstrating hemoperitoneum, large ruptured subcapsular splenic hematoma, and large pelvic mass |

FIGURE 2. Axial CT again showing hemoperitoneum and large subcapsular splenic hematoma |

Atraumatic Splenic Rupture

The first documented case of atraumatic splenic rupture was recorded by Rokitansky in 1861, and the condition was specifically defined by Weidemann in 1927 as “rupture resulting from an incident without external force”.1 This definition was further delineated in 1966 to distinguish atraumatic rupture of a pathologic spleen from true “spontaneous splenic rupture” of a normal, healthy spleen.1 Atraumatic splenic rupture is quite rare, so there is a significant lack of information regarding its typical clinical presentation, general pathophysiology, and guidelines for management.

Currently the majority of descriptions within the literature are in the form of case reports with only a handful of published retrospective reviews.

Additionally, due to its rarity, the exact incidence of atraumatic splenic rupture is unknown, however, one retrospective review looked at 251 cases of splenic rupture, and found a total of 8 cases identified as atraumatic rupture with an estimated incidence rate of around 3.2%.2 Atraumatic rupture tends to occur more commonly in males and has an estimated associated mortality rate of around 12.2-20%.2,3

The majority of cases of atraumatic splenic rupture involve a spleen with some form of underlying pathology. There are many conditions associated with its occurrence; however, a systematic review found that the most common associated conditions are hematologic malignancies, viral infections, and systemic or local inflammatory conditions[3]. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, acute leukemia, mononucleosis, CMV, amyloidosis, and chronic pancreatitis were the most common specific conditions.3 Further literature review found that anticoagulation use and active malaria infections are additional conditions that can lead to atraumatic splenic rupture.4,5

ED Management of Splenic Injury and Hemorrhage

The majority of splenic injury and hemorrhage presenting to the ED will be of traumatic etiology, specifically blunt abdominal trauma most commonly from an MVC.6 Therefore, initial management is to perform a primary survey to address any issues with airway, breathing, and circulation following ATLS protocol.

Concurrently, large bore IV access should be established, and resuscitation initiated. Following the primary survey and initial interventions, the next step is to determine stability of the patient. If the patient is unstable, FAST exam should be performed to identify sources of hemorrhage. An unstable patient with signs of significant abdominal injury with associated peritonitis or positive FAST exam should undergo an emergent surgical evaluation and be taken to the operating room for laparotomy.7 Additionally, these patients should receive resuscitation with emergency release blood products, and any anticoagulation that may be present should be reversed. Ultimately, in the unstable patient, splenic rupture will most likely be identified during laparotomy and managed via splenectomy.7

Conversely, patients who are stable may undergo further workup in the ED with CT imaging to identify the grade and severity of the splenic injury. Once identified, surgical consultation will be needed to determine operative versus nonoperative management. Nonoperative management focuses on less invasive and conservative treatments such as embolization or close observation with repeat abdominal exams and trending of hemoglobin and hematocrit.

Some indications for when to consider embolization include: Grade III injuries or greater, presence of contrast blush, active extravasation, or moderate to severe hemoperitoneum.7 The decision to perform operative versus nonoperative management may vary depending on additional injuries or complications, surgeon preference, local resources, and facility practice.

The management of atraumatic splenic rupture is not too dissimilar to that of traumatic splenic injury. Initial focus should be on ABCs and establishing IV access to begin blood product resuscitation and management of any hemodynamic instability. Surgical management via splenectomy does seem to be the most common treatment of atraumatic splenic rupture, especially in cases of hemodynamic instability or underlying malignancy.8 Patients with low grade rupture or those who are hemodynamically stable tend to be managed with less invasive measures similar to the treatment of traumatic injuries. This includes embolization or even conservative management with close observation, especially in the cases of atraumatic splenic rupture in pediatrics with an underlying infectious etiology.8 Regardless of the underlying cause of atraumatic rupture, the role of the emergency physician is to accurately make the diagnosis, stabilize patients with significant hemorrhage, and make the appropriate consultation for definitive management.

Case Conclusion

Upon stabilization of the patient in the emergency department, the emergency surgical team promptly took the patient to the OR where an exploratory laparotomy was performed. Approximately 6 liters of blood and clot was present within the abdomen and removed throughout the operation. Additionally, the operative report described the removal of the spleen which demonstrated a complete rupture of the splenic capsule. The patient tolerated the surgery well and post-operatively she was resuscitated in the surgical ICU with several more units of blood products. She received her post-splenectomy vaccinations and was ultimately discharged from the hospital on postoperative day four with general surgery and gynecological-oncology follow up. Pathologic examination of the spleen did not show any evidence of metastatic disease and the spleen appeared grossly normal. The patient tested negative for mononucleosis and did not have any associated underlying hematologic malignancy. The exact cause of rupture in this case was of undetermined etiology.

References

- Weaver H, Kumar V, Spencer K, Maatouk M, Malik S. Spontaneous splenic rupture: A rare life-threatening condition; Diagnosed early and managed successfully. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:13-15. doi:10.12659/AJCR.883739

- Jian Liu, Yanyu Feng, Ang Li, Chunqing Liu, Fei Li, "Diagnosis and Treatment of Atraumatic Splenic Rupture: Experience of 8 Cases", Gastroenterology Research and Practice, vol. 2019, Article ID 5827694, 5 pages, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/5827694

- P Renzulli, A Hostettler, A M Schoepfer, B Gloor, D Candinas, Systematic review of atraumatic splenic rupture, British Journal of Surgery, Volume 96, Issue 10, October 2009, Pages 1114–1121, https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.6737

- Kocael PC, Simsek O, Bilgin IA, et al. Characteristics of patients with spontaneous splenic rupture. Int Surg. 2014;99(6):714-718. doi:10.9738/INTSURG-D-14-00143.1

- Gedik E, Girgin S, Aldemir M, Keles C, Tuncer MC, Aktas A. Non-traumatic splenic rupture: report of seven cases and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(43):6711-6716. doi:10.3748/wjg.14.6711

- Akoury T, Whetstone DR. Splenic Rupture. [Updated 2020 Aug 21]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-.

- Stassen, Nicole A. MD; Bhullar, Indermeet MD; Cheng, Julius D. MD; Crandall, Marie L. MD; Friese, Randall S. MD; Guillamondegui, Oscar D. MD; Jawa, Randeep S. MD; Maung, Adrian A. MD; Rohs, Thomas J. Jr MD; Sangosanya, Ayodele MD; Schuster, Kevin M. MD; Seamon, Mark J. MD; Tchorz, Kathryn M. MD; Zarzuar, Ben L. MD; Kerwin, Andrew J. MD Selective nonoperative management of blunt splenic injury, Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery: November 2012 - Volume 73 - Issue 5 - p S294-S300 doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182702afc

- Tonolini M, Ierardi AM, Carrafiello G. Atraumatic splenic rupture, an underrated cause of acute abdomen [published correction appears in Insights Imaging. 2016 Aug;7(4):647]. Insights Imaging. 2016;7(4):641-646. doi:10.1007/s13244-016-0500-y.