The etiologies of small bowel obstructions may vary between underdeveloped and developed nations, but the presenting signs and symptoms of an acute bowel obstruction are similar. When it occurs in a remote area of Eastern Honduras, management becomes more complex - making it an alarming finding.

Small bowel obstruction (SBO) is a common gastrointestinal condition often warranting acute surgical intervention in developed nations because digested material is prevented from passing through the bowel normally. Patients may present with abdominal bloating, constipation, inability to pass stool, nausea, vomiting, or diffuse abdominal pain, typically with guarding. It is estimated that more than 300,000 laparotomies per year are performed in the United States alone for adhesion-related obstructions.1 Common risk factors for SBO in developed countries include prior abdominal/pelvic surgeries, abdominal wall or groin hernias, intestinal inflammation, prior radiation, or history of foreign body ingestion.

In underdeveloped countries, where access to surgical capabilities and other modern health care technologies are limited, the risks for acute intra-abdominal pathologies are shifted toward environmental exposures, such as parasitic infections.

Case Report

A 15-year-old indigenous female presented to a medical missionary clinic in the remote territory of La Moskitia in eastern Honduras with a 3-month history of poor appetite, nausea, worsening epigastric pain, and new onset of vomiting. The patient had been seen recently at a health clinic in her local village, where she was diagnosed with gastritis. After achieving no relief with antacids, her mother brought her to the transient medical clinic established by a team of health care professionals from the United States.

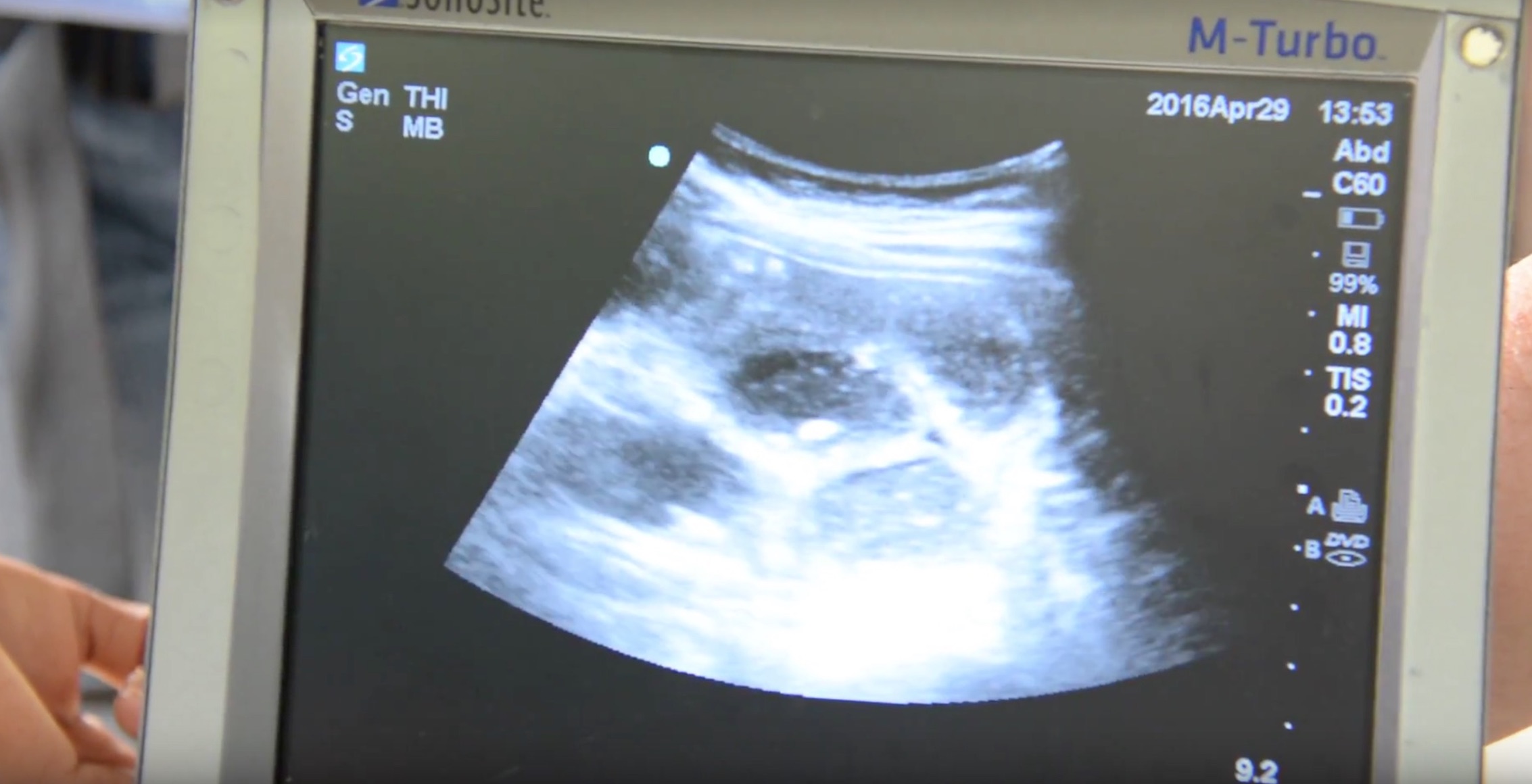

On initial examination, the patient had diffuse abdominal tenderness with generalized guarding. She appeared weak and uncomfortable. Further investigation with a portable ultrasound revealed a small bowel obstruction of unknown etiology (Figure 1).

The patient had not had any previous abdominal surgeries and the cause of her evident bowel obstruction remained unknown. With a quick urge to vomit, the patient quickly ran outside and began expelling roundworms that were greater than a foot in length within her emesis (Figure 2).

It was logically assumed that the cause of this patient’s SBO was a parasitic infection. In such a remote area, this patient was at best 2 hours by boat and 4 hours by car to the nearest hospital with surgical capabilities, located in La Ceiba, Honduras. Her transfer was prepped and she was quickly sent on a long journey to reach the medical care she required (Figure 3).

Discussion

Ascariasis is a common parasitic infection in underdeveloped nations. It is caused by the roundworm Ascaris lumbricoides, which lives in the intestines of its infected hosts and transmits eggs through the feces of its hosts.2

The most common routes of entry for roundworms include oral ingestion from drinking water in which the parasite’s eggs are present, or subcutaneously through bare feet that come in contact with infected feces. Ascariasis is common in locations where there is poor hand hygiene, poor sanitization, and use of human feces as soil.

The eggs of the parasite first hatch in the intestines of its infected host and the larvae move into the bloodstream, where it establishes residency in the lungs.3 After a process of maturing, the roundworms leave the lungs and travel into the trachea, where they are expectorated or swallowed into the esophagus. The worms that are ingested travel back into the intestines, where they continue to grow, mate, and produce additional eggs. The cycle continues as eggs are either excreted through the feces or hatch in the intestines and travel to the lungs via the bloodstream.

An uninterrupted progression of the parasitic infection can lead to small bowel obstruction as the roundworms reproduce in the intestines to a level that impedes the normal flow of digestive material through the GI tract.

As the digestive tract becomes obstructed, the patient will begin to experience generalized abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and poor appetite. If left untreated, the condition can lead to death as the patient becomes dehydrated or the bowels are perforated by a worsening obstruction.

Treatment

Ascariasis infections can typically be treated by common anthelmintic drugs, such as albendazole, ivermectin, and mebendazole.4 In advanced cases causing SBO, surgical intervention requiring enterotomy or resection may be necessary if the complete obstruction does not improve within 24-48 hours.5

Case Conclusion

Although our patient was young, she lived in an undeveloped location where hand hygiene and sanitization are poor, and exposure to human feces is common. There has also been a well-established relationship between malnutrition and intestinal helminth infection, which is common in such a remote area.2

The medical capabilities available within her surrounding location were minimal, and our medical missionary teams’ yearly travel to this territory is the only access many of these individuals have to modern health care. Given the widespread prevalence of helminthic infections, our team treats all patients empirically with albendazole during our visit.

However, in the case of this 15-year-old girl with a small bowel obstruction, her infection was too advanced for this treatment. She was transferred to the closest hospital with modern health care capabilities in La Ceiba, Honduras, where she was admitted and monitored closely. Her ascariasis-associated intestinal obstruction was managed conservatively with appropriate anthelmintic therapy and did not require enterotomy or resection.

References

1. Bordeianou L, Yeh DD. Epidemiology, clinical features, and diagnosis of mechanical small bowel obstruction in adults. In: W. Chen, MD, PhD, ed. UpToDate. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

2. Bethony J, Brooker S, Albonico M, Geiger SM, Loukas A, Diemert D, Hotez PJ. Soil-transmitted helminth infections: ascariasis, trichuriasis, and hookworm. Lancet. 2006;367:1521–1532.

3. Dold C, Holland CV. Ascaris and ascariasis. Microbes Infect. 2011;13(7):632-637.

4. Ortiz JJ, Chegne NL, Gargala G, Favennec L. Comparative clinical studies of nitazoxanide, albendazole and praziquantel in the treatment of ascariasis, trichuriasis and hymenolepiasis in children from Peru. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2002;96(2):193-196.

5. Teneza Mora NC, Lavery EA, Chun HM. Partial small bowel obstruction in a traveler. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(2):256-258.