From the December 2013 issue of Emergency Medicine Practice, “An Evidence-Based Approach To Acute Aortic Syndromes.” Reprinted with permission. To access your EMRA member benefit of free online access to all EM Practice, Pediatric EM Practice, and EM Practice Guidelines Update issues, go to www.ebmedicine.net/emra, call 1-800-249-5770, or email ebm@ebmedicine.net.

- “The D-dimer was negative, so I assumed the patient did not have an aortic dissection and sent him home.”

While D-dimer has shown promise in the evaluation of possible acute aortic dissection, there have been no large prospective studies to validate this strategy. Unfortunately, no biomarkers currently have been validated to rule out an aortic dissection. Intramural hematoma or aortic dissections with a thrombosed false lumen can have a false negative D-dimer. If there is sufficient clinical suspicion for an acute aortic dissection, advanced imaging is indicated. - “The patient didn't have tearing chest pain, a pulse or blood pressure differential, or a widened mediastinum on chest x-ray; therefore, he couldn't have an aortic dissection.”

While studies have shown a decreased probability for an aortic dissection when none of these features are present, this strategy has not been validated to safely rule out an aortic dissection. Approximately 5% of acute aortic dissections will not have any associated pain, and 38% will not have a widened mediastinum on chest x-ray. - “The patient was only 28 years of age and had reproducible chest pain. I thought the patient had costochondritis, so I sent him home with NSAIDs. I didn't know he could have had an aortic dissection!”

While acute aortic dissections usually occur in those who are older, they can occur at any age. Patients with a history of (or suspected) Marfan syndrome, another connective tissue disorder, or a history of a bicuspid aortic valve should always have aortic dissection in the differential. A thorough history and physical examination should be performed to evaluate for all possible risk factors. - “She was 56 years of age, with chest pain and a slightly elevated troponin. I thought it was acute coronary syndromes, and I anticoagulated her while waiting for the cardiologist to see her.”

Although acute coronary syndromes are more common than acute aortic dissection, aortic dissection should always be considered in anyone who presents with chest pain, even with elevations in cardiac biomarkers. History of connective tissue disorder, bicuspid valve, or illicit drug use (such as cocaine) should increase suspicion. Studies have shown missed aortic dissections to be more likely diagnosed as acute coronary syndromes. Evaluation of the chest x-ray and a good history and physical examination can help risk stratify patients for possible aortic dissection. - “She was 65 years old and presented with syncope without chest pain or shortness of breath. I thought it might have been an arrhythmia, so I just admitted her to a telemetry bed.”

Approximately 12% of patients with aortic dissection will have syncope. Elderly patients may not have classic symptoms associated with aortic dissection. - “The patient had an inferior wall STEMI on ECG and the cardiologist was unavailable to take the patient emergently to the heart catheterization lab. I gave thrombolytics because that is what I was told to do.”

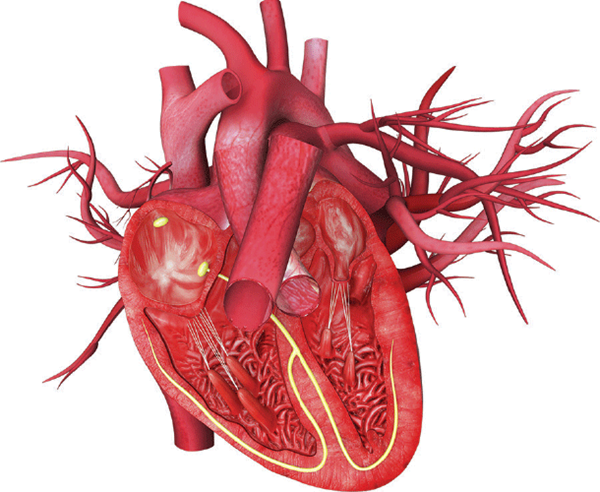

Two percent to 5% of patients with aortic dissections will have concurrent myocardial ischemia. Proximal aortic dissections can dissect into the right coronary artery, causing occlusion, and can present with a STEMI. If clinical suspicion for aortic dissection is present, other diagnostic modalities should be used to evaluate for proximal aortic dissection prior to anticoagulation or thrombolytics. - “The patient was 28 years old and had Marfan syndrome. I was concerned about an aortic dissection, but he couldn't get a CT scan due to a contrast allergy. I got a TEE and it didn't show an aortic dissection, so I sent him home and told him to follow up with his primary care provider.”

Advanced imaging such as TEE, CT, and MRI are all very sensitive and specific; however, no modality is 100%. If there is a high clinical suspicion for an aortic dissection, a second modality should be obtained to rule out aortic dissection. - “The patient presented within an hour, had right hemiparesis, and was unable to speak. He was having a stroke and was within the window for thrombolytics.”

Acute neurological deficits can be found in up to 30% of acute type A aortic dissections, as the dissection extends into the internal carotids or to the spinal arteries. Thrombolytics in the setting of an acute aortic dissection can be fatal. Consider aortic dissection in patients who present with stroke symptoms, especially when patients have concurrent chest or back pain.