Case Report

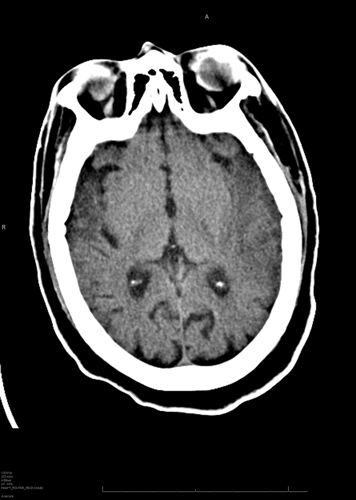

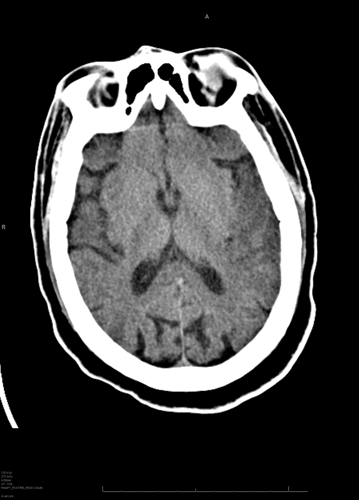

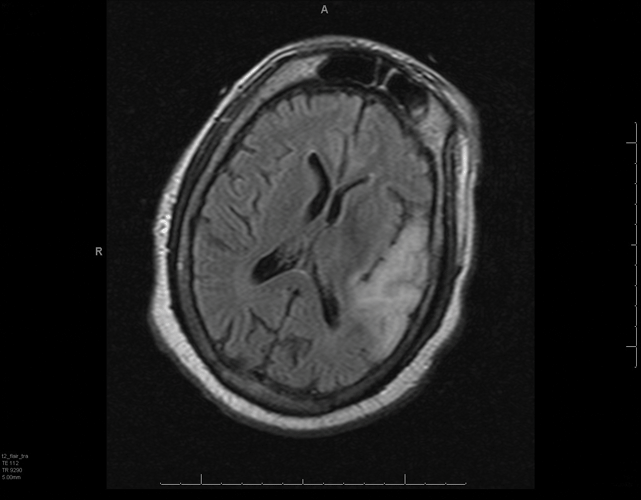

A 49-year-old male presents to the emergency department with two days of confusion, agitation, and speech abnormalities. His vital signs are normal. Physical examination reveals a disoriented and agitated man who does not follow commands, but a neuro exam is non-focal. A CT of the head is shown (Figure 1, Figure 2). An LP was performed, and empiric acyclovir, vancomycin, ampicillin, and ceftriaxone were started. An MRI after admission to the ICU (Figure 3) showed temporal lobe enhancement; a CSF analysis, with cryptococcus antigen, HIV, bacterial and fungal cultures, and HSV PCR, were all negative.

Viral encephalitis, in particular herpes simplex encephalitis, though rare, should remain on the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with altered mental status.

Discussion

Altered mental status is a very common presentation to the emergency department with an extremely broad differential that includes toxins, infections, metabolic and electrolyte disturbances, vascular events, trauma, seizures, and neoplasms. One uncommon, but potentially fatal, cause that is often overlooked is viral encephalitis. In the United States, the most common etiology of viral encephalitis remains herpes simplex virus (HSV), type 1, the diagnosis in this case scenario. Herpes simplex encephalitis has an annual incidence of approximately 1-2 per 500,000 and a mortality rate of around 11%.1 It has a bimodal distribution with approximately one-third of cases occurring in those under 20 years of age and one-half of cases in those over 50. In the United States, approximately 95% of cases are seen in Caucasians.1 Early recognition is essential as prognosis is directly related to early administration of antivirals; prior to the introduction of antiviral treatment, mortality rates were around 70%.2 Current mortality rates are six times higher in the immunocompromised.3

Encephalitis may be differentiated from the other etiologies of altered mental status by the presence of fever (92%), headache (81%), personality changes (85%), and dysphasia (76%), and the absence of nuchal rigidity and photophobia.1 The altered sensorium of encephalitis usually takes the form of cognitive impairment with behavioral disturbances, agitation, disorientation, anterograde amnesia, and occasionally symptoms of loss of inhibition and hypersexuality. Other symptoms can include seizures, focal neurologic findings, speech abnormalities, and obtundation.1

Initial management of encephalitic patients includes appropriate stabilization and fever control, in conjunction with routine blood work, neuroimaging, and cerebrospinal fluid analysis. The gold standard for diagnosis remains a brain biopsy, though this carries a high risk of adverse events.4 Traditionally, serologic studies for herpes simplex virus have been used, but titers are positive in only about 50% of patients at four weeks post-onset, rendering this test only retrospectively informative at best. The most useful test has become cerebrospinal fluid analysis with PCR for HSV. HSV PCR has a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 98%.1,5 CSF analysis is normal in 3%-5% of biopsy-proven cases of HSV encephalitis, but clinical outcome is correlated with viral load; therefore, positive cases with negative results tend to fall on the less critical end of the spectrum.1,2

Neuroimaging is important for the diagnosis, as well as for ruling out other etiologies. Computed tomography (CT) is readily available in most EDs, though it is only moderately sensitive and specific for viral encephalitis.6 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is both much more sensitive and specific.7,8 Classic findings include hypoattenuation of the bilateral temporal lobes and limbic areas on CT, as seen in the image from the patient scenario (Figures 1 and 2), and corresponding hyperintensities on T2 or FLAIR (fluid attenuated inversion recovery) sequences on MRI.2

Optimization of long-term outcomes of herpes encephalitis depends upon early administration of antivirals. Depending on the patient, empiric antibiotics may also likely be indicated. First-line recommendations include acyclovir 10 mg/kg IV every eight hours for 14-21 days.9,10 Initiation of treatment should not be delayed for diagnostic testing. Early initiation has been defined as: before loss of consciousness, within 24 hours of the onset of symptoms, and when the Glasgow Coma Score is 9-15.11 The role of adjunctive steroid therapy is controversial. Some studies have shown increased viral replication secondary to immune suppression with the addition of steroids.12,13,14 Unfortunately, even with early initiation of treatment, nearly two-thirds of patients will still have long-term sequelae and 1% will be in a persistent vegetative state.9 Memory problems, verbal and cognitive deficits, visual problems, and anosmia have all been described as complications.15

Conclusion

Viral encephalitis, in particular herpes simplex encephalitis, though rare, should remain on the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with altered mental status. When the diagnosis is suspected, treatment should begin immediately without delay for results of confirmatory testing.

References

- Whitley RJ. Herpes simplex encephalitis: adolescents and adults. Antiviral Research; 71:141-148, 2006.

- Stahl JP, Mailles A, Dacheux L, et al. Epidemiology of viral encephalitis in 2011. Med Maladies Infect; 41(9):453-64, 2011.

- Tan IL, McArthur JC, Venkatesan A, et al. Atypical manifestations and poor outcomes of herpes simplex encephalitis in the immunocompromised. Neurology; 79(21):2125-32, 2012.

- Whitley RJ, Gnann JW. Viral encephalitis: familiar infections and emerging pathogens. Lancet; 359:507-514, 2002.

- Whitley RJ, Cobbs CG, Alford CA et al. Diseases that mimic herpes simplex encephalitis: diagnosis, presentation, and outcome. JAMA; 262(2):234-239, 1989.

- Schroth G, Gawehn J, Thom A, et al. Early diagnosis of herpes simplex encephalitis by MRI. Neurology; 37:179-83, 1987.

- Steiner I, Budka H, Chaudhuri A, et al. Viral encephalitis: a review of diagnostic methods and guidelines for management. Eur J Neurol; 12:331-43, 2005.

- Hindmarsh T, Lindqvist M, Olding-Stenkvist E, et al. Accuracy of computed tomography in the diagnosis of herpes simplex encephalitis. Acta Radiol Suppl; 369:192-6, 1986.

- Whitley RJ, Kimberlin DW. Herpes simplex encephalitis: children and adolescents. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis; 16(1):17, 205.

- Tyler KL. Herpes simplex virus infections of the central nervous system: encephalitis and meningitis, including mollaret's. Herpes; 11 Suppl 2:57A, 2004.

- Whitley RJ, Soong SJ, Linneman C et al. Herpes simplex encephalitis: clinical assessment. JAMA 247(3):317-320, 1982.

- Nakano A, Yamasaki R, Miyazaki S et al. Beneficial effect of steroid pulse therapy on acute viral encephalitis. Eur Neurol; 50:225-9, 2003.

- Ramos-Estebanez C, Lizarraga KJ, Merenda A. A systematic review on the role of adjunctive corticosteroids in herpes simplex virus encephalitis: Is timing critical for safety and efficacy? Antivir Ther; Sep 6. doi: 10.3851/IMP2683. [Epub ahead of print], 2013.

- Musallam B, Matoth I, Wolf D, et al. Steroids for deteriorating herpes simplex virus encephalitis. Pediatr Neurol; 37(3):229-32, 2007.

- Gordon B, Selnes OA, Hart J et al. Long term cognitive sequelae of acyclovir treated herpes simplex encephalitis. Arch Neurol; 47(6):646, 1990.