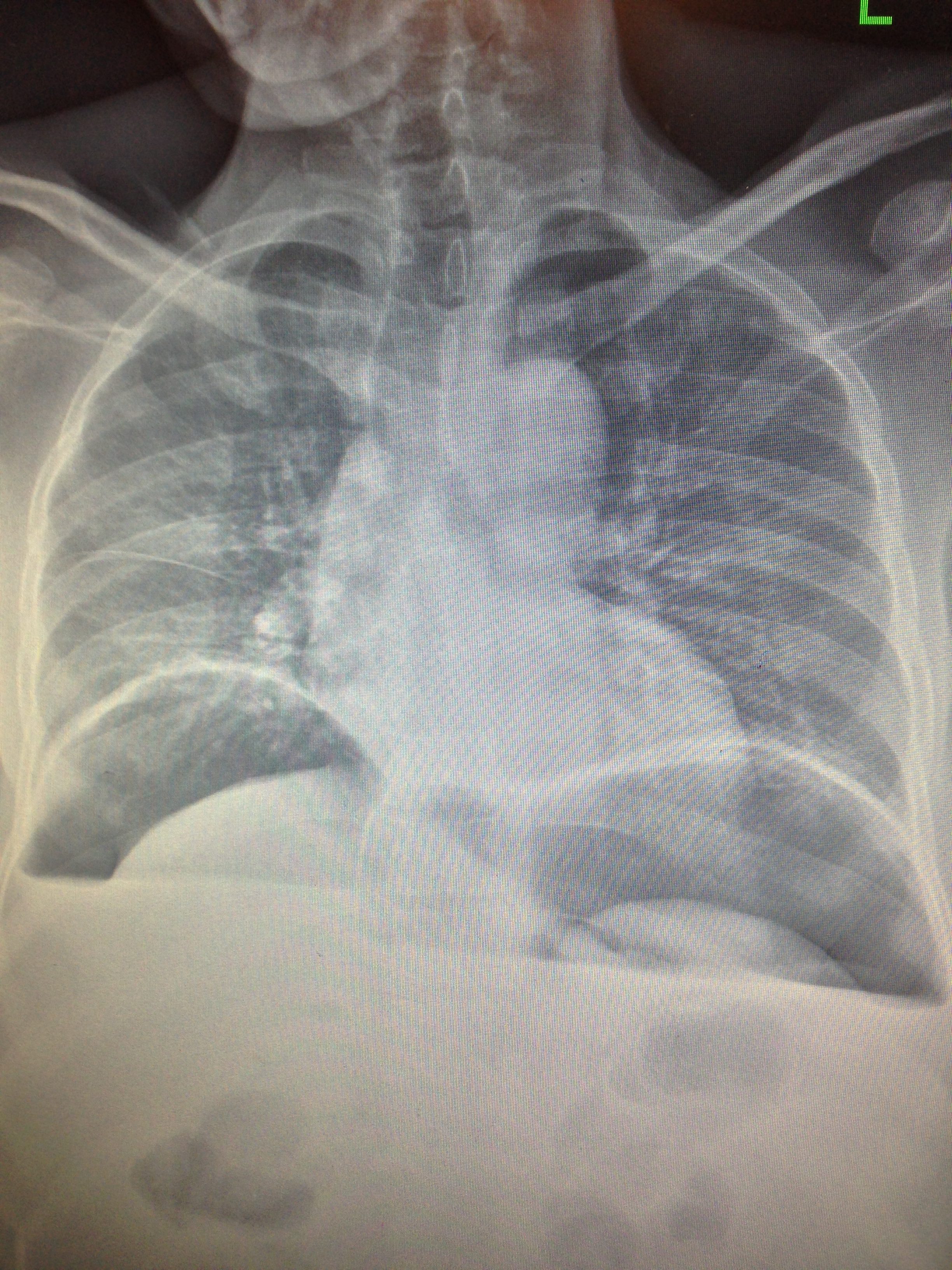

A 64-year-old male with a past medical history of peptic ulcer disease presents to the Tamale Teaching Hospital (TTH) Emergency Department (ED) in Tamale, Ghana, with worsening abdominal pain. He has no fever, nausea, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea, but his abdomen is distended and rigid. Despite an impressive exam, he is lying upside down on the stretcher with one foot in the air and his legs crossed. He smiles at you as he rates his pain a 4/10. He cannot afford a CT, but he can afford an upright chest radiograph (Figure 1). He receives antibiotics and eventually goes to the operating room for his perforated peptic ulcer. Unfortunately, he dies post-operatively.

One of the most astounding things about working in a northern Ghanaian ED was encountering such resilient people. Their tolerance for pain, unwavering support for family members, and gratitude for assistance was unlike anything I have previously come across. Although the system is fraught with limitations due to resources and frustration for the indigent, it highlighted people's ability, even without all of the machines and medications and fancy gadgets, to endure.

Operating with 11 beds, no functioning monitors, and 3 triage spaces, this ED likely sees more trauma than the average American emergency medicine training program on any given day. Due to the sheer volume of motorcycle riders and lack of helmet adherence, road traffic accidents are a regular occurrence. As a result, the TTH ED manages a veritable neurological/surgical ICU patient population, but with far fewer resources.

Since November 2015, the ED has transformed completely due to the presence of 2 brand-new emergency medicine physicians, Dr. Offei and Kwame Ekremet, MD, who trained at the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital in Kumasi, Ghana. The ED was previously staffed by medicine and surgery physicians, and the area was first intended to be a holding bay for pre- and post-op patients.

Emergency medicine residency in Ghana began in 2010, and Drs. Offei and Ekremet graduated from the fourth class. The residency was one of numerous projects funded by a $130 million U.S. National Institutes of Health/Fogarty International Center grant to expand and improve health care in Africa that came into existence thanks to the Ghanaian Emergency Medicine Collaborative with the University of Michigan.

The TTH ED finds itself in a precarious position of having to prove its worth among the other hospital departments. It is still in the beginning stages of collecting visitation data, training nurses and staff, and teaching its medical students and interns the unique field of emergency medicine.

Despite being a large hospital and a tertiary referral center, the ED at TTH struggles to keep the electrocardiogram machine and automated external defibrillator to itself, as they are shared among various departments. If the intensivist goes on vacation, the ICU closes. If a family cannot afford to pay the 270 Ghanian Cedis (approximately $70) for a CT scan, then it will not be done. EMS functions primarily for hospital-to-hospital transfers, and families often take on the role of nurses. The saving grace of this ED is its motivated and intelligent physicians with strong physical examination skills, who truly know the meaning of sick and not sick. It is not uncommon to see disseminated tuberculosis, malaria, and very late presentations of malignancies. The patients themselves also seem to have a good grasp of the system's limitations and an admirable acceptance of their own mortality.

TTH is a convergence of high acuity, interesting pathology, and ingenuity. The utilization of bedside ultrasound helps immensely, as other testing can be delayed while families gather the money to pay for services. It is emergency medicine stripped down to its core, and the department establishment in northern Ghana is an awe-inspiring new frontier for our field.