Ch. 2 - Migraine

David H. Cisewski, MD, MS | Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Benjamin W. Friedman, MD, MS | Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Current estimates suggest more than 1 million patients visit the ED annually for acute migraine attacks.1 Not only are these attacks debilitating, but the management is also complicated by a wide range of analgesic regimens, none of which offer guaranteed relief.

More than 20 different migraine medications are currently used. Yet, less than 25% of patients achieve sustained headache relief (> 48 hrs), indicating we still fall well short of optimal management.2 Additionally, many of the analgesic options we currently use cause debilitating side effects such as drowsiness, dizziness, restlessness, akathisia, and dry mouth. What we need is an analgesic regimen that is not only quick and efficacious but also contains minimal side effects to return the patient to their baseline quality of life.

DEFINING MIGRAINES

Migraine is a clinical disorder that lacks definitive laboratory or neuroimaging findings. Migraines are defined as recurrent headaches (at least five life-time headaches), not associated with another disease pathology, lasting 4-72 hours with at least 2 of the following characteristics:3

- Unilateral location

- Pulsating quality

- Moderate/severe intensity

- Aggravated by physical activity

Additionally, the diagnosis of migraine must include either photophobia/phonophobia or nausea/vomiting.3

To effectively manage pain, we must recognize the individual, subjective nature of each patient's pain presentation and treat it safely and effectively using available research data. Additionally, an accurate diagnosis will allow patients to access appropriate care as an outpatient and at future ED visits. A common question is whether there is a need to distinguish migraine-specific headaches from alternative headache subtypes in the emergency setting. Though migraine is not synonymous with "severe headache," patients with moderate to severe headaches often respond to a similar analgesic regimen. When the diagnosis is unclear and severe causes of headache have been safely ruled out, a migraine regimen may be considered for all moderate to severe headaches.

MIGRAINE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Although anchoring bias may focus attention on a classic migraine presentation, particularly in patients with a history of migraines, consideration must be given to other benign and life-threatening causes of migraine-mimics.

Benign: Along with migraines, benign causes of headache include tension headaches, cluster headaches, trigeminal neuralgia, post-lumbar puncture headaches, sinusitis, coital headaches, medication overuse headache, and low/ high CSF pressure headaches such as post-dural puncture headache.

Deadly: More dangerous and potentially life-threatening causes of headaches (along with associated can't-miss red flags) include: carbon monoxide toxicity (family with headaches), temporal arteritis (temporal tenderness, jaw claudication, age > 50 years), subarachnoid and other forms of intracranial hemorrhage ('worst headache of my life,' maximal at the onset, anticoagulant use), cervical artery dissection (neck trauma, unilateral face pain, ptosis & miosis), cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (thromboembolic risk factors, recent brain/ face surgery), idiopathic intracranial hypertension (obesity, transient visual obscurations, papilledema), preeclampsia (current/recent pregnancy), meningitis/encephalitis (fever and neck stiffness, altered mental status, immunocompromised state, and space-occupying lesion such as malignancy (weight loss, history of malignancy).

TREATING MIGRAINES

A migraine is often a debilitating form of headache. It may be resistant to first-line oral medications used for mild/moderate pain such as acetaminophen (975 mg PO) and ibuprofen (400 mg PO). For migraines resistant to oral acetaminophen/ibuprofen combinations, several non-opioid alternatives exist. The optimal migraine medication should have a safe, quick-onset, maximal efficacy, limited side effects, and allow for sustained headache relief. To date, this optimal combination does not exist. Of the 1 million patients presenting to the ED each year for migraine treatment, opioids are still being used in the majority of treatment plans, with hydromorphone being the analgesic of choice in approximately one-fourth of the cases.1 However, research has demonstrated superior analgesic relief with non-opioid alternatives4, and several other alternatives have been shown to treat migraines safely and effectively. The following is an evidence-based list of migraine treatment options that may be utilized in the emergency setting:5,6

Standard first-line migraine treatment options for moderate to severe pain include metoclopramide (10 mg IV), prochlorperazine (10 mg IV), chlorpromazine (12.5 mg IV), haloperidol (5 mg IV), or droperidol (2.5 mg IV or IM). Though the specific frontline analgesic depends on the patient's past success and current presentation, metoclopramide (10 mg IV) is considered an optimal, evidence-based first-line agent.7,8 Prochlorperazine has also demonstrated superiority over opioids for acute migraine relief but should be administered with 25 mg diphenhydramine to avoid extrapyramidal side effects.9,10 Both metoclopramide and prochlorperazine should be administered slowly over a 15-minute infusion to avoid akathisia.9 Chlorpromazine (12.5 mg IV) has also been shown to be as effective as metoclopramide. It should also be administered slowly over 20-30 min.11,12 Among patients with a normal cardiac QT length, the antidopaminergics haloperidol and droperidol may also be considered first-line options. Droperidol (2.5 mg IV) has been shown to be at least as effective as prochlorperazine for acute pain reduction of benign acute headaches in the emergency setting.13,14 Haloperidol (5 mg IV) has also been shown to be as efficacious as metoclopramide (10 mg IV) for acute headaches in the emergency setting though with increased restlessness.8

Dexamethasone (10 mg IV) reduces headache recurrence within 72 hours of ED discharge (NNT = 9)15, as well as decrease the need for repeated analgesic use during the emergency presentation.16 Additionally, magnesium (1 g IV) may offer similar effect to decrease current and repeat migraines, though the evidence is mixed and most suggestive in treating migraine with aura.17,18

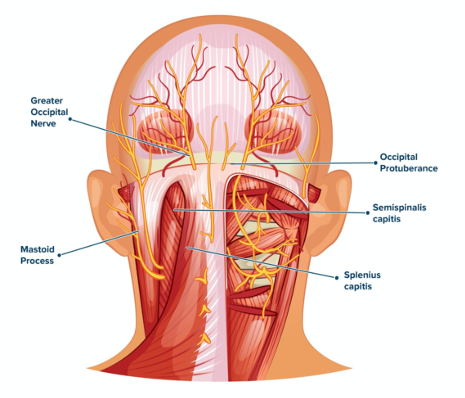

A nerve block may also be considered in patients with moderate to severe occipital headaches. Nerve blocks have been used for migraines for years with the greater occipital nerve (GON) being a major target.19,20 The GON is composed of sensory fibers that derive from the C2 spinal nerve, providing cutaneous innervation to the majority of the posterior scalp.21 The theoretical rationale for the GON block (GONB) for migraines derives from the convergence of its neurons with trigeminal nerve fibers, which have been implicated in migraine.21,22 (Note: This convergence pattern also accounts for the location of pain distribution with migraines, which often includes both anterior and posterior regions of the head/upper neck.) The greater occipital nerve innervates the posterior scalp bilaterally. The following 3-step landmark technique can be used to identify the greater occipital nerve on each side of the scalp:23

- Place index finger on the occipital protuberance.

- Place thumb on the mastoid process (either right or left side).

- Measure one-third the distance between two points extending from the occipital protuberance.

This is the approximate location of the greater occipital nerve as it extends up from its exit from the semispinalis capitis muscle at approximately the C1/C2 position (*GON often noted as the point of maximal tenderness).

Once identified, 3–5 mL of 1% to 2% lidocaine or 2–4 mL of 0.25% to 0.5% bupivacaine is injected using a 27-gauge needle to infiltrate the GON.21 The optimal technique involves a "fanning technique" in which 1 cc of anesthetic is injected immediately adjacent to the GON, 1 cc medial to the GON, and 1 cc lateral to the GON for maximal infiltration. The "fanning technique" can be repeated bilaterally to cover both GONs.17,18 If continued symptoms, despite 1 hour of assessment, proceed to step five.

Among patients with an unremitting headache following a 30- to 60-minute reassessment, full consideration should be given to alternative diagnoses, particularly the deadly can't-miss diagnosis. For further analgesic relief, consider an alternative first-line analgesic option from those listed above. Additionally, ketorolac (15-30 mg IV)may be added among patients who do not have contraindications to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories.7 Intravenous fluids may be considered among patients who appear dehydrated or who have been vomiting but have not been shown to increase migraine relief when used as an adjunct with other first-line regimens.24

Among patients who show refractory migraines following repeated attempts at the first-line options, second-line alternatives may be considered, such as valproate, sumatriptan, and acetylsalicylic acid. Valproate (1 g IV) may be considered among patients who have previously had a favorable response. However, research has shown decreased efficacy compared to other first-line options (metoclopramide).7 Sumatriptan may also be considered. Although sumatriptan is considered a first-line migraine treatment option in the outpatient setting, it causes many adverse effects (chest tightness, flushing, potentially worse headache) and an increased rate of short-term headache recurrence.25 Additionally, the first-line antidopaminergics have increased efficacy and improved tolerability compared to triptans.26,27 Nevertheless, sumatriptan (6 mg SQ) may be considered among patients who do not have cardiovascular risk factors and who have received a benefit from it during previous migraine attacks. Although ketamine (0.15-0.3 mg/kg IV, 15 min infusion) is not recommended for migraine headaches as it has been shown to be ineffective,28 and also inferior to prochlorperazine for benign headaches,29 it may be considered as a non-opioid alternative for refractory headache pain. If available, addition of acetylsalicylic acid (0.5-1 g IV) may also be considered with efficacy comparable to sumatriptan but with less of a side effect profile.30,31

Propofol (sub-anesthetic dosing – 30–40 mg IV) with repeat boluses of 10 mg every 3-5 min up to 120 mg may be considered as a last resort for refractory migraines.32 The use of propofol is limited by the need for cardiac monitoring and provider observation to avoid over-sedation.

MIGRAINE DISPOSITION

It is essential to set realistic expectations for patients presenting for migraine management. Though many patients will have a defined analgesic regimen that works best for their migraine flairs, most will not and will require trial periods of the above stepwise approach. Dexamethasone (10 mg IV) may assist with prevention, yet up to two-thirds patients will still have migraine relapse in the days following ED visit.2 Be sure to establish outpatient primary care follow up for management and ensure close ED return precautions for warning signs that may suggest an alternative diagnosis such as continued headache suffering, fever, or vomiting with an inability to tolerate oral fluids. Among patients without contraindications, naproxen (500 mg PO) or sumatriptan (100 mg PO) may be prescribed to treat a short-term recurrence of headache after ED discharge.33 A sumatriptan auto-injector (Imitrex) is also available as an easy-to-use administration during an acute headache attack.34 Additionally, acetaminophen or acetaminophen/aspirin/caffeine combination (Excedrin) may be effective in treating the pain and associated side effects of migraine headaches.35,36 The combination acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine (Fioricet) should be avoided due to the increased adverse effect profile, medication overuse headaches, and rebound headaches.37

References

- Friedman BW, West J, Vinson DR, Minen MT, Restivo A, Gallagher EJ. Current management of migraine in US emergency departments: an analysis of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(4):301-309.

- Friedman BW, Hochberg ML, Esses D, et al. Recurrence of primary headache disorders after emergency department discharge: frequency and predictors of poor pain and functional outcomes. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52(6):696-704.

- International Headache Society Classification ICHD-3: Migraines Without Aura. 2018 [cited 2018; Available from: https://www.ichd-3.org/1-migraine/1-1-migraine-without-aura/.

- Friedman BW, Irizarry E, Solorzano C, et al. Randomized study of IV prochlorperazine plus diphenhydramine vs IV hydromorphone for migraine. Neurology. 2017;89(20):2075-2082.

- Orr SL, Friedman BW, Christie S, et al. Management of Adults With Acute Migraine in the Emergency Department: The American Headache Society Evidence Assessment of Parenteral Pharmacotherapies. Headache. 2016. 56(6):911-940.

- Friedman BW. Managing Migraine. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69(2):202-207.

- Friedman BW, Garber L, Yoon A, et al. Randomized trial of IV valproate vs metoclopramide vs ketorolac for acute migraine. Neurology. 2014;82(11):976-983.

- Gaffigan ME, Bruner DI, Wason C, Pritchard A, Frumkin K. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Intravenous Haloperidol vs. Intravenous Metoclopramide for Acute Migraine Therapy in the Emergency Department. J Emerg Med. 2015;49(3):326-334.

- D'Souza RS, Mercogliano C, Ojukwu E, et al. Effects of prophylactic anticholinergic medications to decrease extrapyramidal side effects in patients taking acute antiemetic drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Emerg Med J. 2018;35(5):325-331.

- Vinson DR, Drotts DL. Diphenhydramine for the prevention of akathisia induced by prochlorperazine: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37(2):125-131.

- Cameron JD, Lane PL, Speechley M. Intravenous chlorpromazine vs intravenous metoclopramide in acute migraine headache. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2(7):597-602.

- Bigal ME, Bordini CA, Speciali JG. Intravenous chlorpromazine in the emergency department treatment of migraines: a randomized controlled trial. J Emerg Med. 2002;23(2):141-148.

- Miner JR, Fish SJ, Smith SW, Biros MH. Droperidol vs. prochlorperazine for benign headaches in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8(9):873-879.

- Weaver CS, Jones JB, Chisholm CD, et al. Droperidol vs prochlorperazine for the treatment of acute headache. J Emerg Med. 2004;26(2):145-150.

- Colman I, Friedman BW, Brown MD, et al. Parenteral dexamethasone for acute severe migraine headache: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials for preventing recurrence. BMJ. 2008;336(7657):1359-1361.

- Latev A, Friedman BW, Irizarry E, et al. A Randomized Trial of a Long-Acting Depot Corticosteroid Versus Dexamethasone to Prevent Headache Recurrence Among Patients With Acute Migraine Who Are Discharged From an Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;73(2):141-149.

- Delavar Kasmaei H, Amiri M, Negida A, Hajimollarabi S, Mahdavi N. Ketorolac versus Magnesium Sulfate in Migraine Headache Pain Management; a Preliminary Study. Emerg (Tehran). 2017;5(1):e2.

- Bigal ME, Bordini CA, Tepper SJ, Speciali JG. Intravenous magnesium sulphate in the acute treatment of migraine without aura and migraine with aura. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Cephalalgia. 2002;22(5):345-353.

- Gawel MJ, Rothbart PJ. Occipital nerve block in the management of headache and cervical pain. Cephalalgia. 1992;12(1):9-13.

- Caputi CA, Firetto V. Therapeutic blockade of greater occipital and supraorbital nerves in migraine patients. Headache. 1997;37(3):174-179.

- Ashkenazi A, Levin M. Greater occipital nerve block for migraine and other headaches: is it useful? Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2007;11(3):231-235.

- Bartsch T, Goadsby PJ. Stimulation of the greater occipital nerve induces increased central excitability of dural afferent input. Brain. 2002;125(Pt 7):1496-1509.

- Friedman BW, Mohamed S, Robbins MS. A Randomized, Sham-Controlled Trial of Bilateral Greater Occipital Nerve Blocks With Bupivacaine for Acute Migraine Patients Refractory to Standard Emergency Department Treatment With Metoclopramide. Headache. 2018; 58(9):1427-1434.

- Jones CW, Remboski LB, Freeze B, Braz VA, Gaughan JP, McLean SA. Intravenous Fluid for the Treatment of Emergency Department Patients With Migraine Headache: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;73(2):150-156.

- Akpunonu BE, Mutgi AB, Federman DJ, et al. Subcutaneous sumatriptan for treatment of acute migraine in patients admitted to the emergency department: a multicenter study. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25(4):464-469.

- Friedman BW, Corbo J, Lipton RB, et al. A trial of metoclopramide vs sumatriptan for the emergency department treatment of migraines. Neurology. 2005;64(3):463-468.

- Kostic MA, Gutierrez FJ, Rieg TS, Moore TS, Gendron RT. A prospective, randomized trial of intravenous prochlorperazine versus subcutaneous sumatriptan in acute migraine therapy in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(1):1-6.

- Etchison AR, Bos L, Ray M, et al. Low-dose Ketamine Does Not Improve Migraine in the Emergency Department: A Randomized Placebo-controlled Trial. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19(6):952-960.

- Zitek T, Gates M, Pitotti C, et al. A Comparison of Headache Treatment in the Emergency Department: Prochlorperazine Versus Ketamine. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;71(3):369-377 e1.

- Diener HC. Efficacy and safety of intravenous acetylsalicylic acid lysinate compared to subcutaneous sumatriptan and parenteral placebo in the acute treatment of migraine. A double-blind, double-dummy, randomized, multicenter, parallel group study. The ASASUMAMIG Study Group. Cephalalgia. 1999;19(6):581-588; discussion 542.

- Taneri Z, Petersen-Braun M. [Double blind study of intravenous aspirin vs placebo in the treatment of acute migraine attacks.]. Schmerz. 1995;9(3):124-129.

- Moshtaghion H, Heiranizadeh N, Rahimdel A, Esmaeili A, Hashemian H, Hekmatimoghaddam S. The Efficacy of Propofol vs. Subcutaneous Sumatriptan for Treatment of Acute Migraine Headaches in the Emergency Department: A Double-Blinded Clinical Trial. Pain Pract. 2015;15(8):701-705.

- Friedman BW, Solorzano C, Esses D, et al. Treating headache recurrence after emergency department discharge: a randomized controlled trial of naproxen versus sumatriptan. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(1):7-17.

- Landy SH, Tepper SJ, Wein T, Schweizer E, Ramos E. An open-label trial of a sumatriptan auto-injector for migraine in patients currently treated with subcutaneous sumatriptan. Headache. 2013;53(1):118-125.

- Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Ryan Jr RE, Saper J, Silberstein S, Sheftell F. Efficacy and safety of acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine in alleviating migraine headache pain: three double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Arch Neurol. 1998;55(2):210-217.

- Lipton RB, Baggish JS, Stewart WF, Codispoti JR, Fu M. Efficacy and safety of acetaminophen in the treatment of migraine: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(22):3486-3492.

- Feeney R. Medication Overuse Headache Due to Butalbital, Acetaminophen, and Caffeine Tablets. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2016;30(2):148-149.