Ch 10. Funding: Show Me The Money!

Introduction

Finding funding for your global health project may seem like a daunting task, but with a little hunting you will find there are many sources willing to invest in the right match. Funding sources range from local institutions to national foundations that are willing to support initiatives of varying scope, from modest two-week clinical missions to ambitious multi-year campaigns. In this chapter, you will find tips for composing a strong grant proposal and a breakdown of available resources. However, given that opportunities change so frequently, it is impossible to list every possibility. We encourage everyone reading this to take the information learned below and explore yourself.

The Well-Written Proposal

General Format

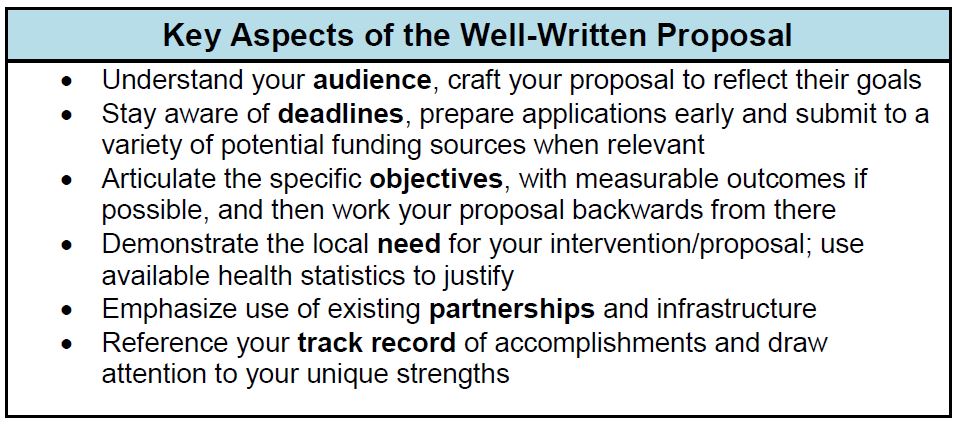

The cornerstone of convincing an organization or institution to provide you with funding is a written proposal of your project. Proposal writing is an art unto itself and our goal in this section is merely to introduce general concepts, to get you thinking, and to provide resources for further study. The style of proposal will vary tremendously depending on the scope of the project and the intended audience; however, a proposal will usually include goals and objectives, methods for meeting these goals, anticipated outcomes, how you will measure these outcomes, and anticipated problems that you may run into along the way.

- Goals/Objectives: The goals of your selected project should be discrete, measurable, and reflect the interests of the organization(s) to whom you are submitting. Quantifiable objectives will appeal to a broad spectrum of potential supporters, rather than nebulous outcomes that can be ambiguous. Be careful to set achievable goals. Make certain that they are appropriate to the scope of your project, the local need/interest, your personal experience, and available resources. When conceptualizing your project, start with these to ensure that your methods and intervention will be described in a clear and focused manner and that their significance will be unambiguous.

- Methods: How will you reach these goals set at the beginning of the proposal? How will you measure/evaluate/analyze this outcome? These should be straightforward, uniform, and as detailed as possible.

- Anticipated Outcome: Be careful not to overstate your potential impact of your proposal. Reviewers are experienced individuals and exaggeration is not appreciated.

- Limitations: The more forthcoming you are with limitations, the more likely you will be funded. It demonstrates that you are realistic and pragmatic as a project lead.

Writing/Submitting Tips

Partnerships

When crafting the description of your intervention, be sure to emphasize any existing partnerships or infrastructure that you will be leveraging. Take advantage of bridges already built to add a sense of achievability for your proposal.

Past Accomplishments

The same applies to emphasizing your personal achievements. Donors will be more inclined to support projects pioneered by applicants who have been able to demonstrate successful outcomes in the past. For those just starting out, draw attention to relevant past accomplishments that have given you the skills you will need in this new endeavor.

Timeliness/Persistence

Submit applications early and often to a variety of groups in order to increase the likelihood of securing timely funding. One of the most important points to consider when writing a proposal for funding is knowing the closing date for grant applications well in advance. Lack of awareness to deadlines, or starting the process too late, may mean a weaker application and missing ideal funding opportunities. You may need signatures from your program leaders, department heads and deans prior to submission.

Research

Consider reviewing successful proposals submitted by peers and mentors to appreciate appropriate tone, content, depth, and breadth.

Expectations

Keep realistic expectations! Understand your selected target and your chances of being funded, and remember that not every proposal will be funded. In addition do not get discouraged by early rejection. Seek feedback from reviewers on missing or weak elements of your application and adjust your applications accordingly.

Locating Funding

When looking for funding, begin with what is closest to you, and work out from there. Although the award may be comparatively smaller, the closer the funding source is to you, the more likely you are to gain funding. So start at the institutional level and work out from there.

Institutional

Residency/Medical School

Begin your hunt for funding closest to home. For residents, this should start with a frank discussion with your chairman, program director, or research director regarding availability of funds within the residency for travel support or international programs. In addition, faculty with global health or research interests can be excellent resources to help you locate sources of funding. Your chairman and program director can help you locate faculty, recent graduates, and fellow residents with global health interests. Similarly, medical students should begin by approaching the appropriate dean’s office for help, but should also consider their affiliated emergency medicine residency leadership as a resource.

Broader Institution

The next step should be an evaluation of funding sources at the institutional level. Many medical schools have grants or memorial funds from alumni or local philanthropic groups that can be used to fund medical student and resident initiatives. These funds are often disbursed as fellowships, grants, and travel awards. These awards may be administered by a global health programs office that can guide students through the application process, so contact your institution’s office or appropriate dean to explore this option. For residents, institutional grants are often administered by individual departments or by the employing hospital. However, these grants may not be restricted to residents within one department. Consider contacting departments outside of emergency medicine who have ongoing partnerships abroad, most commonly internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, or infectious disease.

Local and Regional

Professional Organization Chapters

Most national organizations also have state chapters that may provide access to state-specific funds and grants that can be designated towards a global health project. General medical societies at the state or regional level may also distribute grants for resident projects, so check with organizations in your area. Additionally, regional chapters of national civic organizations receive far fewer applications than their national counterparts - this substantially increases your chances of winning an award. Organizations to consider include, but are not limited to, the Lions Club, Rotary, Jaycees, etc.

Cultural or Religious Organizations

Area-specific ethnic, cultural or religious organizations are often enthusiastic supporters of global health initiatives targeted towards improving care within their respective region or towards a sister congregation internationally.

Corporations

Similarly, regionally-focused corporations may be interested in engagement if you are introducing a training or medical device that might be relevant to their industry, or you have a personal connection to corporate leadership.

National

Finally, and perhaps most important, is the search for grants at the national level. Application numbers for these grants are usually high and competition is fierce. Organizations providing such grants at the national level include major federal government institutions (CDC and NIH), national professional organizations (ACEP/SAEM), national scholarships or fellowships (Fulbright), major philanthropic foundations (Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation), or large national industry partnerships. It is worth noting that certain programs are available only to select participating institutions.

National Resources for Global Health Funding

- Grants.gov: This federal website provides a searchable, central repository for thousands of federal grants, annually. The website also includes a tutorial on grant applications. Registration to apply for grants is complex, however, and can take over 3 weeks.

- Fogarty International Center: Funding Opportunity Directory: Provided by the NIH’s Fogarty International Center, this website includes a comprehensive list of NIH and non-NIH funding sources for trainees at all career stages..

Long Term Grants (greater than 3mo)

- Doris Duke Charitable Foundation – International Clinical Research Fellowship: This year-long fellowship available to medical students at 6 selected institutions provides support for a year off from medical school to conduct mentored clinical research in a developing country.

- Fulbright Fellowship: Sponsored by the state department, this year-long fellowship is available to US graduates (including medical students and residents) pursuing research abroad. Over 1,000 are issued each year. Proficiency in language of host country is a must.

- Albert Schweitzer Fellowship: This fellowship is awarded to four 3rd year medical students who spend clinical 3 months in pediatrics or medicine in Lambarene, Gabon.

- Fogarty Global Health Program for Fellows and Scholars: This one-year program provides mentorship and research opportunities for early-stage investigators (students and residents) in global health over 8-10 months at designated international sites as part of the Global Health Equity Scholars program.

- Fulbright-Fogarty Fellows and Scholars in Public Health: This partnership allows Fulbright applicants to conduct public health research at Fogarty-affiliated institutions. Application is through the Fulbright Program

Short Term Grants (less than 3mo)

- O.C. Hubert Student Fellowship in International Health: Offered by the CDC, this program for 3rd and 4th year medical students includes a brief orientation at the CDC, followed by placement at a CDC partner site in the developing world for 6 to 12 weeks. It includes $4000 towards total costs.

- Be the Change Challenge: $5000 awarded by EMRA for residents or students willing to “dream big” and pursue a project designed to have an impact on EM education, research, practice, or policy.

- EMRA Research Grant: $1000 awarded for residents or students towards completion of a research project.

- James S. Westra Memorial Endowment Fund (Christian Medical and Dental Associations). $500 awarded quarterly to 3rd/4th year students participating in missionary preceptorship. Requires CDMA membership and letter of support from a pastor.

- Yale/Stanford J&J Global Health Scholars Program Available to residents at 7 institutions, awards $3,000 travel award for 6 week clinical rotation at one of several mentored sites.

- CMDA Johnson Short-Term Mission Scholarship: Up to $1000 awarded to a resident to participate in medical preceptorship or clerkship abroad. Requires CDMA membership and pastor letter of support.

- Wilderness Medicine Society Research Grants: Up to $5000 available to medical students and residents for projects pertaining to wilderness medicine, potentially in a global health setting.

- Emergency Medicine Foundation Medical Student Research Grant: The charity arm of ACEP awards medical student research grant, up to $5,000.

- AMA Seed Grant Research Program: Open to medical students and residents with applicant-conceived project. Not specific to global health.

- American Medical Women’s Association Overseas Assistance Grants: Provides travel grants of up to $1000 for member students and residents working in clinics around the world for at least 4 weeks.

- David E. Rogers Fellowship Program: Five awards of up to $5,000 for medical students between first and second year to embark on a research project focused on the needs of an underserved or disadvantaged population..

- Arnold P. Gold Foundation Student Summer Fellowship: This grant awards a $4,000 stipend to medical students for a service project related to community health.

- AAEM/RSA Medical Student Scholarship: Two yearly awards of $500 for medical students with a passion for emergency medicine. Must be AAEM member and nominated by an attending, fellow or resident.