Mindfulness and the Emergency Medicine Mind

Chapter 1 Audio

INTRODUCTION

The emergency department (ED), except on incredibly rare occasions, is a fast-paced, chaotic environment. By name and by design, it expects providers to work quickly, often making snap decisions based on limited information. This act-now-think-later mentality creeps into all aspects of our lives, often creating stress, anxiety, and emotional distress. One could argue that the inability to think in anything but a reactionary mode is harmful to both our wellness and our clinical practice.

How then can the emergency medicine physician overcome this? There have been numerous studies by neurobiologists and cognitive psychologists to investigate how human beings can modulate their emotional responses to stress and anxiety. Overwhelming evidence has demonstrated that practicing mindfulness, focusing on being aware of one’s thoughts, emotions, and sensations, can help with “quieting the mind.” This allows responding, rather than reacting, to the stressful situation at hand.

WHAT IS MINDFULNESS?

Mindfulness is the basic human ability to be fully present, aware of where we are and what we’re doing, and not overly reactive to or overwhelmed by what’s going on around us. Importantly, mindfulness allows us to take in the present moment but without judgment. It allows us to quiet the ego – the combination of judgements, desires, and assumptions whispered by our inner voice – and to focus on simply being aware. Michael Taft, self-described neuroscience junkie and meditation teacher, describes meditation as “paying attention nonjudgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment."1

Buddhist tradition describes achieving mindfulness as being associated with the breath. Modern mindfulness subscribes to these Buddhist ideals and advocates for Vipassana meditation as one of the ways to practice mindfulness. While the concept of mindfulness has its roots in Buddhist tradition, modern mindfulness and meditation has evolved such that it can be practiced without components of spirituality or religion. Devout Christians, Muslims, and Jews point out that mindful meditation has been part of mystical traditions of all major faiths and plenty of meditation techniques teach the methods of mindful meditation in a secular, scientific context.

THE SCIENCE BEHIND MINDFULNESS

Recent neuroscience studies looking at brain scans of meditating subjects have begun to create a model on how mindful meditation is able to extend cognitive and physical effects. Subjects were placed in an MRI scanner while being asked to train their attention on the sensation produced by breathing. Subjects were asked to hit a button when they found their minds wandering, then restore attention to the gradual rhythm of the inhaling and exhaling. During this exercise, scientists were able to identify four phases of the cognitive cycle: mind wandering, becoming aware of distraction, reorienting attention, and resumption of focused attention, all of which activated different brain networks. They found that compared to novices, veteran meditators showed increased activity in the brain networks that allowed for increased attention and focus but paradoxically had less activation, suggesting that continued meditation allowed subjects to maintain a focused state of mind with less effort – what some might call being in “the zone.”2

MRI scans show that after an eight-week course of mindfulness practice, the amygdala, the region of the brain associated with fear and emotion, appears to shrink. As the amygdala gets smaller, the prefrontal cortex, the region of the brain associated with higher order brain functions such as awareness, concentration, and decision-making, becomes thicker.3 With meditation, primal, automatic responses are downregulated in favor of more thoughtful ones.

There is also recent evidence that breathing itself can activate neural pathways that lead to a meditative calm. In 1991, a group of neuroscientists at the University of California, Los Angeles, discovered the pre-Bötzinger complex, an area containing neurons that fired rhythmically in time with each breath, which functions like a respiratory pacemaker. These same scientists then removed part of the neurons that make up this complex in mice such that the mice breathed more slowly than normal mice. They found that the mice with altered breathing were unusually calm. They discovered these neurons regulating breath also formed connections with the locus coeruleus, another area in the brainstem involved in modulating arousal and emotion.4

This evidence, along with recent discoveries that the brain has great neuroplasticity and can be permanently changed through experience, suggest that similar to practicing a technical skill like intubating, we can train our minds to be calmer, quieter, and more focused.

CLINICAL BENEFITS OF MINDFULNESS

Recently, the medical community has increased awareness of burnout, depression, and even suicide of physicians and other medical professionals. There is growing concern that the deleterious effects of stress, such as difficulty with interpersonal relationships, substance abuse, depression, and anxiety, may develop or become amplified in medical school and residency. Uncontrolled stress can also lead to professional difficulties, and may especially impact humanistic qualities that are crucial to optimal patient care.

It is often suggested that implementing skills and techniques, such as mindfulness and meditation, into daily practice may be one mechanism to combat this growing epidemic. Like any new habit, adopting meditation into a daily routine takes time and is likely to be more beneficial if it is incorporated earlier in life. This is not a new concept, as there have been numerous studies examining mindfulness in medical students as a means of stress reduction. A group of psychologists at the University of Arizona studied a cohort of 200 pre-medical and medical students in 1998, and introduced them to a short course on meditation-based stress reduction interventions. At the completion, they noted a significant reduction in self-reported anxiety, in overall psychologic distress, and an increase in overall empathy level scores.5 More recently, researchers in Australia published a similar study this year, but instead they narrowed their subject group to EM interns. After a 10-week intervention, their findings were consistent with the results of the medical student study: participants reported a large and significant reduction in stress and symptoms of burnout.6

A growing number of leaders in the EM community are becoming more intrigued by the practice of mindfulness in everyday life. In a recent talk, Scott Weingart likens the benefits of meditation to those of exercise; instead of working out to live longer, he calls meditation work “to live better.” Per Weingart, one of the key objective benefits to mindfulness is that it offers the practitioner the ability to choose their response to different situations and stimuli. Through the practice of mindful meditation, one develops the ability to create a “space” between the stimuli and the response. This space is a period of decision-making time, which allows the practitioner a brief moment to choose a reaction.7 A practiced meditator may develop an awareness of his/her emotions and thoughts, and prevent them from becoming out of control or creating mental distress. In the ED, providers often face a range of emotions and difficult situations throughout the day. Instead of getting angry at a frustrating situation, for example, a provider may be able to channel those emotions more effectively and respond to the stimulus in a less reactive way.

The beneficial effects of meditation are numerous. Many practitioners describe better stress control, improved insight into one’s emotions and body sensations, heightened concentration, and an overall deeper appreciation of the good things in one’s life. One of the founding principles of meditation is being present and aware, without being judgmental or overwhelmed. After mastering this, normal daily irritants or distractors become less disruptive. This may translate in the ED to something as simple as the ability to ignore a beeping monitor or something more intense like tolerating an angry consultant. Mindfulness has the potential to be an extremely important asset to the daily life and practice of medical providers: It can be easily implemented, can be practiced just about anywhere, and is the most non-invasive form of treatment for psychological distress.

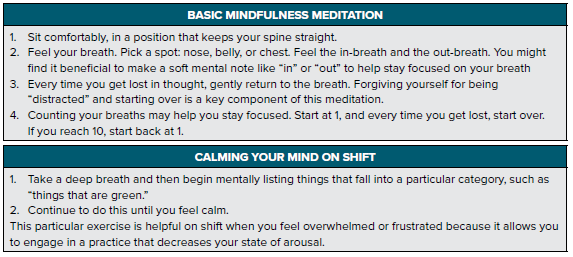

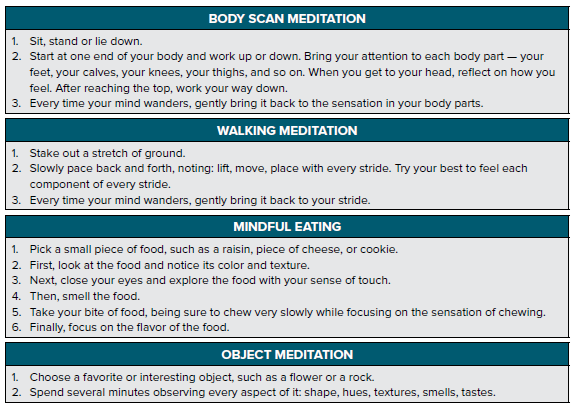

SAMPLE MEDITATION EXERCISES

RECOMMENDED APPS, BOOKS, AND WEB RESOURCES

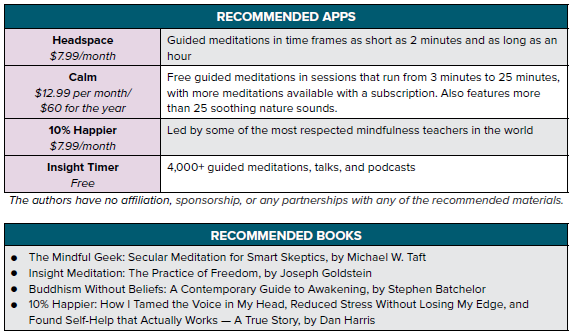

Recommended Apps

The authors have no affiliation, sponsorship, or any partnerships with any of the recommended materials.

Podcasts / Websites

- All It Takes is 10 Mindful Minutes TED Talk by Andy Puddicombe

- Free Guided Meditations from UCLA Mindful Awareness Research Center

- EMCrit - Vipassana Meditation

- The Overwhelmed Brain - a podcast on personal growth, with episodes on meditation and banishing negative thoughts

- Mindfulness in Plain English

The authors have no affiliation, sponsorship, or any partnerships with any of the recommended materials.

REFERENCES

- Taft MW. The Mindful Geek: Secular Meditation for Smart Skeptics. Oakland, CA: Cephalopod Rex Publishing; 2015.

- Ricard M, Lutz A, Davidson R. Mind of the Meditator. Scientific American. 2014;11(5):38-45.

- Taren A, Creswell J, Gianaros P. Dispositional Mindfulness Co-Varies with Smaller Amygdala and Caudate Volumes in Community Adults. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e64574.

- Kwon D. Meditation’s Calming Effects Pinpointed in the Brain. Scientific America. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/meditations-calming-effects-pinpointed-in-brain/. Published March 30, 2017. Accessed August 10, 2017.

- Shapiro SL, Schwartz GE, Bonner G. Effects of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction on Medical and Premedical Students. J Behav Med. 1998;21(6):581–599.

- LeBlanc VR. The Effects of Acute Stress on Performance: Implications for Health Professions Education. Acad Med. 2009;84:S25–S33.

- Weingart S. Podcast 182 – Kettlebells for the Brain – Meditation from SMACC 2016. EMCrit Blog. Published September 19, 2016. Accessed June 1, 2017.

- Harris D. 10% Happier: How I Tamed the Voice in My Head, Reduced Stress without Losing My Edge, and Found Self-Help That Actually Works: a True Story. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers; 2014.