Treat Your Body Right

Chapter 5 Audio

IMPACT OF SHIFT WORK ON OVERALL HEALTH

In the United States, 1 in every 5 working men and women are shift workers. Considerable research has studied the deleterious effects of this schedule on general health and wellness – and emergency physicians are not spared.1 There is a negative impact on diet and exercise and the consequences of shift work could even account for the reduction in average life span among shift workers compared to the general population.2

Studies have shown that variable working hours have led to changes in eating patterns and the effect of food on the body. From a physiologic perspective, endocrine changes can account for many of these behaviors. Night workers have shown a decrease in melatonin and other hormonal changes that account for the disruption of quality sleep, a higher rate of diabetes, and an increase in weight gain.3 Furthermore, shift workers tend to eat more than those who work a regular day schedule.4 The long-term consequences of these changes contribute to an increased rate of metabolic syndrome.

DIET

As discussed, dietary changes are common in shift workers, and the reasons behind them are multi-factorial. First, changes in secretion of hunger hormones account for an increased desire to consume more food at night. The lack of available options during overnight shifts means fewer healthy food alternatives. To exacerbate matters, emergency physicians are constantly busy, with limited or no break time – which incentivizes snacking on food that is nutritionally sparse. We explore how to combat these poor dietary habits many shift workers are predisposed to.

Establishing Eating Habits

Residents often feel guilty for taking time during a shift to eat. This leads to increased hunger and possibly decreased performance. Enforcing dedicated meal times can increase productivity during the shift and improve long-term wellness.

Preparing your meals in bulk on off-days before a string of consecutive shifts is time-efficient and means you would not have to cook every night. Most cooked food, particularly meat and vegetables, can be stored up to 4 days in the refrigerator without risk of contamination. Food stored in the freezer can last several months.

An alternative is subscribing to a meal-delivery service. Local and national companies offer a range of options. Meals are usually delivered cooked and prepared and only require re-heating, ideal for residents on busy schedules.

Meal Kit / Delivery Services

Meal Kit Services

Prepared Delivered Meals

The authors have no affiliation, sponsorship, or any partnerships with any of the recommended materials.

Hospital Cafeteria

Most hospital cafeterias offer healthy options as well as an abundance of nutritionally suboptimal options (“comfort food” for patients’ family members in times of stress). Avoid the quick, less healthy options (eg, pizza, fries, etc.) in favor of more nutritionally dense alternatives. Many may find it to be beneficial to purchase food before work and store it in the physician lounge refrigerator for mid-shift consumption.

Food-Based Beverages and Meal Replacements

Alternatives to sitting down and eating a full meal include meal replacement shakes and beverages (eg, Soylent www.soylent.com, Ample www.amplemeal.com). Many of these products can vary significantly in nutrition; carefully read the nutritional profile so you obtain the adequate amount of micro- and macronutrients each day. This is a good option for particularly busy shifts when you do not have time to sit for a full meal.

Nutrition

The field of nutrition science is inherently complex and extremely difficult to study; randomized-control trials are difficult to conduct because of the prevalence of many confounders. Most studies are epidemiological and expert dietary recommendations seem to change year to year. Depending on your needs and goals, current body weight/composition, and general activity level, your ideal total caloric intake and macronutrient (carbohydrate/fat/protein) ratios may vary widely from another individual.

The AHA, Academized, and USDA recommend diets high in fruits and vegetables and low in fat, especially trans-fat and saturated fats.5 However, this conventional evidence has been challenged by recent epidemiological studies showing low carbohydrate-high fat diets may actually contribute to more weight loss and a decrease in metabolic syndrome.6,7 The well-regarded Mediterranean diet is high in monounsaturated fats (eg, olive oil, legumes) and has been suggested to lower cardiovascular events and mortality.8,9

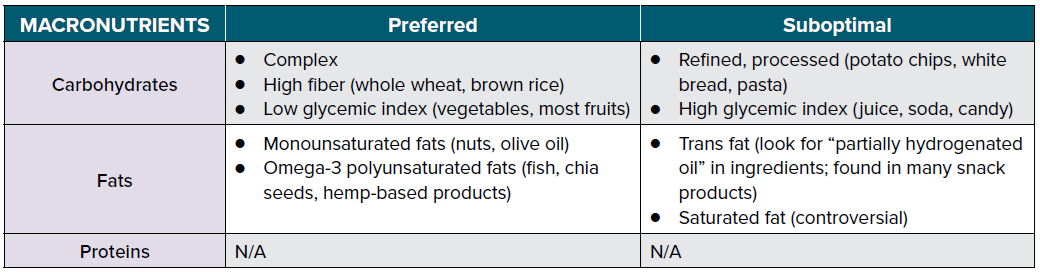

Despite these differences among various recommendations, there is some consensus: the total number of calories matter, but so do the type of calories.10 Macronutrient ratios play a strong role, as do the attributes of each macronutrient. Refined, processed, and high glycemic index carbs are harmful because they contribute to insulin resistance. Trans-fats are deleterious because they can lead to elevated cholesterol and triglyceride levels. The majority of experts recommend eating a diet consisting of complex, low glycemic index carbohydrates and non-trans fats.

EXERCISE

If there is one “drug” that can be deemed a miracle drug, backed by extensive research for its multitude of health benefits, it is exercise. However, keeping up with a consistent regimen is particularly challenging for busy EM residents with variable schedules from week to week. The most obvious and well-known benefit of exercise is its effect on physical fitness, but its value surpasses that. Here, we discuss the importance of physical activity for body, brain, and sanity.

Benefits of Exercise

It has been well-documented that consistent aerobic exercise is associated with reduction in mortality from heart disease, cancer, and all-cause mortality.11,12 That in itself should be enough reason to exercise regularly during residency.

However, there is also a large body of evidence to support aerobic activity’s benefits on both short-term and long-term cognition.13-16 Consistent cardiovascular activity can increase your focus during work and can potentially improve your performance. If possible, go for a jog, cycle, or swim before your shift as you may be more exhausted after work. There is no evidence of any cognitive benefit from anaerobic exercise (eg, lifting weights).

Epidemiologic studies suggest that aerobic exercise may also reduce anxiety and rates of depression.17 Because physicians have high rates of these mood disorders, those who conduct steady physical activity may find enormous benefits. Those who exercise regularly also report enhanced mood and greater overall happiness.18 This can especially helpful during periods of burnout.

Create an Exercise Plan and Stick to It

The first step in designing an exercise plan is reflecting on your goals. Your objectives may be to gain or lose weight, increase muscle mass, decrease fat composition, prevent the onset of metabolic syndrome, improve cognitive performance, or combat mental illnesses.

A strict exercise regimen is especially difficult for shift workers as working hours vary from week to week. Therefore, it is critical to plan your workouts in advance so you adhere to a schedule. Here are some tips to stick with your exercise plan throughout residency:

- Sign up for a workout class on your weekly protected day to better adhere to attendance.

- Schedule your workout sessions in your calendar for the entire week at the beginning of the week, with exact times.

- Pair with a co-resident on a similar schedule each month to exercise together.

- Find a gym that is open late so you do not skip workouts during a series of overnight shifts.

- Consider incorporating exercise in your commute to work by walking or biking if feasible.

Exercise on Shift

No time to work out during residency? Well, there is evidence showing decreased fatigue, increased vigor, and improved cognitive function just by taking 5-minute walks intermittently throughout the day.19 Here are some tips to sneak in some physical activity on shift:

- Use the stairs instead of the elevator.

- Take frequent brisk walks between prolonged bouts of sitting and documentation.

- Fidget at your workstation to burn more calories and increase blood circulation in the extremities.20

- Download the “7 Minute Workout” app.

References

- Smith-Coggins R, Broderick KB, Marco CA. Night shifts in emergency medicine: the american board of emergency medicine longitudinal study of emergency physicians. J Emerg Med. 2014;47(3):372-8.

- Machi MS, Staum M, Callaway CW. The relationship between shift work, sleep, and cognition in career emergency physicians. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(1):85-91.

- Ulhôa MA, Marqueze EC, Burgos LG, Moreno CR. Shift work and endocrine disorders. Int J Endocrinol. 2015;2015:826249.

- Mirick DK, Bhatti P, Chen C, Nordt F, Stanczyk FZ, Davis S. Night shift work and levels of 6-sulfatoxymelatonin and cortisol in men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(6):1079-87.

- Mozaffarian D, Ludwig DS. The 2015 US Dietary Guidelines: Lifting the Ban on Total Dietary Fat. JAMA. 2015;313(24):2421-2.

- Mansoor N, Vinknes KJ, Veierød MB, Retterstøl K. Effects of low-carbohydrate diets v. low-fat diets on body weight and cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Nutr. 2016;115(3):466-79.

- Tobias DK, Chen M, Manson JE, Ludwig DS, Willett W, Hu FB. Effect of low-fat diet interventions versus other diet interventions on long-term weight change in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(12):968-79.

- Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(14):1279-90.

- Bloomfield HE, Koeller E, Greer N, MacDonald R, Kane R, Wilt TJ. Effects on Health Outcomes of a Mediterranean Diet With No Restriction on Fat Intake: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(7):491-500.

- Ludwig DS. Lowering the Bar on the Low-Fat Diet. JAMA. 2016;316(20):2087-2088.

- Lee DC, Pate RR, Lavie CJ, Sui X, Church TS, Blair SN. Leisure-time running reduces all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(5):472-81.

- Ladenvall P, Persson CU, Mandalenakis Z. Low aerobic capacity in middle-aged men associated with increased mortality rates during 45 years of follow-up. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23(14):1557-64.

- Raichlen DA, Bharadwaj PK, Fitzhugh MC. Differences in Resting State Functional Connectivity between Young Adult Endurance Athletes and Healthy Controls. Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:610.

- Nokia MS, Lensu S, Ahtiainen JP. Physical exercise increases adult hippocampal neurogenesis in male rats provided it is aerobic and sustained. J Physiol. 2016;594(7):1855-73.

- Kodali M, Megahed T, Mishra V, Shuai B, Hattiangady B, Shetty AK. Voluntary Running Exercise-Mediated Enhanced Neurogenesis Does Not Obliterate Retrograde Spatial Memory. J Neurosci. 2016;36(31):8112-22.

- Morris JK, Vidoni ED, Johnson DK. Aerobic exercise for Alzheimer's disease: A randomized controlled pilot trial. PloS One. 2017;12(2):e0170547.

- Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Sui X. Are lower levels of cardiorespiratory fitness associated with incident depression? A systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Prev Med. 2016;93:159-165.

- Lathia N, Sandstrom GM, Mascolo C, Rentfrow PJ. Happier People Live More Active Lives: Using Smartphones to Link Happiness and Physical Activity. PloS One. 2017; 12(1):e0160589.

- Bergouignan A, Legget KT, De Jong N. Effect of frequent interruptions of prolonged sitting on self-perceived levels of energy, mood, food cravings and cognitive function. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13(1):113.

- Morishima T, Restaino RM, Walsh LK, Kanaley JA, Fadel PJ, Padilla J. Prolonged sitting-induced leg endothelial dysfunction is prevented by fidgeting. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016;311(1):H177-82.