Transitioning from Medical Provider to Medical Student

Matthew Carvey MSIV, EMT-P, FP-C, TP-C - St. George’s University

EMRA MSC International Representative, 2021-2022

Medic-1 is responding to an assault in a rural location. Dispatch notifies EMS that the patient

has a fever and was put on mandatory self-isolation for 14 days. On arrival, EMS dons a sterile

cap, goggles, an N95 mask, face shield, gown and gloves. The patient, belligerent and

intoxicated on alcohol and psilocybin, yells at EMS ‘I have the COVID!’. She rushes EMS,

removes the practitioner’s mask, and coughs in his face. Police arrest the woman under the

Mental Health Act, and EMS transports, only for her to spit and verbally abuse them the entire

length of transport. EMS unloads the patient and awaits triage. One of the practitioners displays

signs of COVID-19 three days later. This case summarizes the all-too-familiar circumstances

many healthcare practitioners face while on the job. The primary purpose of this article is to

highlight the difficulties these previous providers have during medical school.

The COVID-19 pandemic has united the medical community – physicians, nurses, respiratory

therapy, and EMS (among many other examples) – in the singular purpose of containing the

virus. With this comradery comes shared challenges, such as fear of contracting the virus,

overwhelming PPE shortages and frontline staff burnout. Because of these concerns facing

society, a unique population of medical providers, as listed above, have taken on the trials of

becoming a medical student to pursue their vision of becoming a physician. This is not an easy

adjustment, with many challenges not typically found in your average student. Below are a few

of those issues that may arise, and some advice on how to deal with them.

- The difficulty of becoming a backseat driver in patient care after being the primary

provider. A major struggle of those with previous lead experience in medicine is that of

now becoming the one learning rather than doing. A way to overcome this is

remembering why you decided to pursue medical school in the first place, to seek a

higher level of knowledge. The diagnostic pathways assumed during your previous career

were geared towards a certain threshold, and thinking beyond this into continuity of care

is now your prime motive. For example, as a paramedic we are taught to stabilize a

patient to the best of our ability; however, we have minimal concern about the

longitudinal outcome of the patient. As an aspiring physician, you are also thinking in the

here and now, but also the long-term effects that can result directly from your actions. - Utilizing your skills in a previous profession to better yourself as a medical student.

What many former practitioners don’t realize as medical students is that they are still an

integral part of the team, where they can use their experience of the past to assist in ways

those without prior applicable skills cannot. However, you must understand that your

actions are not under your licence, but under the licence of the resident, fellow and/or

attending. Just because you may have placed chest tubes and central lines in the past

doesn’t mean you will during clinical rotations based on the previous fact. Showing your

confidence and familiarity with certain skills will inspire preceptors to allow you to go

beyond the medical students “scope of practice”, but this should not be expected. Utilize

your abilities to assist your team wherever they may need it, and this might mean cleaning

up the stool once in a while regardless of your practical history. - How to defuse after being pushed to the sidelines during patient care when you

know what needs to be done next. The most notable issue facing those with past

experience is knowing what needs to be done next, but your input being essentially

thwarted. The best example of this for paramedics will be during resuscitations. It is

difficult to watch a tube being misplaced, or an IV being done when an IO is indicated,

but the primary purpose of your transition to medical school was to understand the next

steps (thinking beyond just the resuscitation). Defusing after these situations is important,

as frustrations can build if you continue to concern yourself with these circumstances.

Talk with a resident you are comfortable with, as they may have similar feelings. Chat

with an old co-worker who you can comfortably convey your thoughts to. They may be

able to offer further insight, especially into affairs you may not have considered, such as:

“What is the definitive care for this patient?” Maybe it’s ECMO for that massive PE, or

bronchoscopy for an FBO that can’t be visualized. These are all steps you may be less

familiar with, and are being thought of at the time by the primary team, rather than the

basics such as IVs and intubation.

As previous healthcare practitioners you have transitioned to a very difficult time in your life,

becoming a student once again. With this, issues will arise that are not common to the average

medical student who goes directly from undergraduate studies to medical school. However,

remembering why you decided to become a physician in the first place is key. Not only can you

bring a distinct level of understanding to your clinical studies, but your prior experience can be

beneficial to the primary team while you simultaneously strengthen your knowledge in becoming

a future physician.

Related Content

Jun 11, 2021

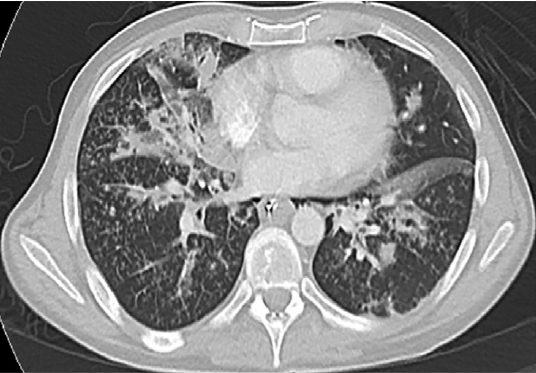

Pulmonary Manifestations Following IV Injection of Crushed Suboxone: A Case of Excipient Lung Disease

Include excipient lung disease (ELD) in the differential diagnosis when evaluating and treating a patient with a history of intravenous drug use presenting with respiratory failure and typical findings on chest imaging.