Ch. 6 - Crush Your Clerkships, Secure Your SLOEs

Three years of hard work have flown by and you have earned the opportunity to demonstrate your skills and explore emergency medicine. Two of the most important factors of your application, your clerkship grades and your SLOEs, are a result of your rotation performance. These factors carry a significant weight in how most programs determine interview invitations and rank order list position. You’re about to begin your EM rotation and you have one burning question:

What can I do to really stand out and make a positive impression during my clerkship?

First, remember some basic practices that may seem small but in reality will be the foundation of your performance.

- Be on time. Even better, be early. Showing up late to a shift or didactic session can seem unprofessional and demonstrate a lack of enthusiasm. If you need to miss a day or will be late, notify your clerkship director as soon as possible. During an away rotation, take into account the commute time from your housing to your clinical site before your first day.

- Dress appropriately. Ask how you are expected to dress on-shift (scrubs, business casual, white coat, etc.), during conferences, and in didactic sessions.

- Be enthusiastic. Your enthusiasm for learning will be noticed quickly and much appreciated. It will also help you get the most out of your rotation.

- Come prepared. Bring your stethoscope, trauma shears, pharmacy guide, medical apps (including calculators), or any other pocket EM guide with you for quick references.

Next, understand that you’re an important member of the team. Your evaluations and plans matter, even if at times you feel they don’t. Along with the nursing staff, you will be the first person to meet patients, and your history and physical will be the foundation of the plan moving forward.

IMG Students: Non-native English speakers will need to demonstrate mastery of the English language to show you can communicate well with both patients and other members of the care team.

Preparing for a Successful Clerkship

It’s important to build your fund of EM-specific knowledge. This occurs before, during, and after clinical rotations. Take advantage of the many resources available to you — not only during your clerkships, but also as you prepare for them and after you crush them.

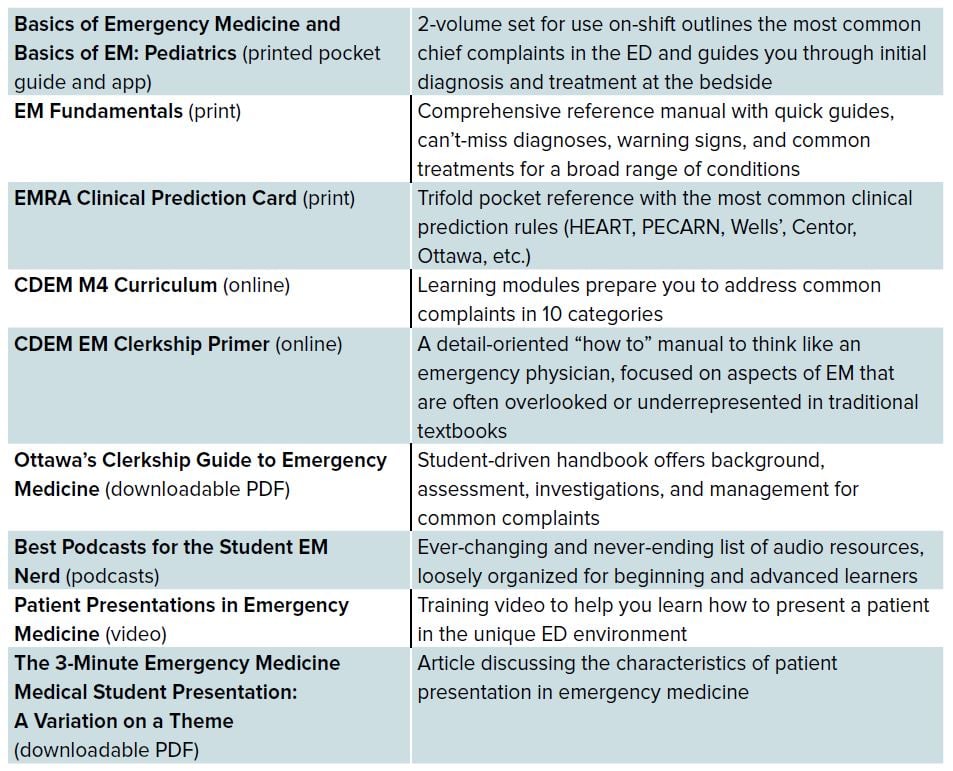

TABLE 6.1. Guidance for EM Learners

You might feel like there’s an overwhelming number of resources; test several of them before your clerkship and use the ones you feel most comfortable with.

Interacting with Patients

While you’re brushing up on the clinical aspects of patient care, don’t forget the patient. It’s important to establish rapport quickly — but that can be challenging when you’re approaching a stranger who’s experiencing a problem grave enough to lead them to the ED. Follow some basic steps:

- Introduce yourself to the patient and explain your role as a medical student.

- Find out who is accompanying them (do not make assumptions).

- Ask why they’re in the ED today (for chronic conditions, find out what made today different than any other day, and research prior treatments).

- Determine if they’ve had any prior work-up relevant to today’s visit and where these records can be located.

- Inquire about their access to follow-up care to help coordinate a safe discharge plan.

- Small things go a long way with patients and their visitors; does the patient need a blanket? A phone to call their loved one? Does their elderly visitor need a chair?

- If your initial impression is the patient is unstable, agitated, or altered, you are probably right, and in such instances it is appropriate to grab your resident or attending immediately to evaluate the patient.

Presenting a Patient

Your oral presentation to your attending is critical in demonstrating your knowledge of patients’ complaints, exams, and management plans. But a patient presentation in emergency medicine is unique. The pace of the ED environment demands extremely succinct presentations that may be interrupted at any given time; be thorough but brief, and be ready to pick up where you left off after any interruptions. Focus your presentation to include the patient’s chief complaint and any information relevant (positive or negative) to the complaint, also noting relevant exam findings. Then present your differential diagnosis, prioritizing the most emergent diagnoses, and discuss your anticipated management plan. While presenting your plan, you may also consider including any consultations you may need, and anticipated final disposition if it is apparent. Be ready to answer any additional questions about the history and physical exam, but this does NOT mean you need to present every detail initially; stick to what you know is relevant to the chief complaint.

Developing a Strong DDx and Plan

Your differential diagnosis should be based on your history and physical exam. Do not rattle off a random assortment of diagnoses, as this reflects poorly on your H&P and on your medical decision-making. Do include all emergent diagnoses in your differential, even those that are less likely or don’t require further work-up, to demonstrate to your evaluator that you’ve considered all possibilities. A good framework to organize your differential is SPIT:1

- Serious

- Probable

- Interesting

- Treatable

Utilize your differential to decide which labs, imaging, and interventions are needed. Familiarize yourself with the clinical prediction rules that your supervising resident or attending will be considering when determining what work-up is needed, such as the HEART Score for ACS, the Wells’ Score and PERC for PEs, Canadian CT Head rule for trauma, etc. Be ready to discuss your anticipated disposition for the patient, including what type of follow-up they might need. If you don’t verbalize your thinking, your supervisor won’t be able to know what you have or haven’t thought about, and won’t be able to give you as meaningful feedback on your presentations. Expect to be quizzed after you present your differential and plan. These questions are not casting doubt on your competence, but rather they enable your evaluator to understand your thought process and provide an opportunity to strengthen or modify your plan.

NEVER LIE. If you didn’t ask a question about a patient’s history, forgot to check for something during your physical exam, or didn’t consider a specific diagnosis when generating your differential, absolutely do not lie! It takes time to gain the trust of your supervisor, but that trust can evaporate quickly. When you are open and honest about what you did or didn’t do, it provides assurance that the rest of your presentation is honest and accurate. You can always go back into a patient’s room to collect the missing information. But if there is even a hint that your presentation was not honest, it creates more work for your supervisors because they must start with a blank slate.

DON'T OVERREACH. There’s a first time for every procedure, and when that’s the case, simply let your supervising physician know you’ve never performed the procedure but you would like to learn and practice. Similarly, if you are asked a question you cannot answer, just say you don’t know, and then go find an answer. Admitting you don’t know something doesn’t show incompetence, it demonstrates humility — and patients and attendings alike will respect this.

"OWN" YOUR PATIENTS. Depending on your rotation and electronic chart access, this can be difficult. In general, you should stay on top of lab/imaging results and recognize their relative impact on care. For example, if a UA comes back suggesting UTI, reporting this to the resident/attending and suggesting an appropriate antibiotic choice and disposition would be excellent care. Remember — anyone can report abnormal findings, but the real question is what to do with those findings.

Ownership also includes updating patients with plans, results, and managing their expectations of their visit. This is easier for you as a student, simply because you’ll have more time than your resident/attending. Show ownership by reassessing after interventions (eg, is the nauseous patient no longer vomiting after receiving antiemetics) and re-evaluating physical exams as needed (serial abdominal exams). Furthermore, inform your attending of any status updates with your patients, reassessments, or results. You are often the best eyes and ears for your attending. Recognizing a critical change or “sick” patient and immediately alerting the ED team of this will always garner respect.

If given tasks to complete (notes, consults, procedures) do them promptly and inform your supervising resident or attending when you’re finished. If you encounter difficulty, that’s OK — just let the team know. If you have completed all tasks for a patient, you can demonstrate initiative by asking to pick up another patient. However, be sure not to pick up so many that you fall behind. You will impress your attending far more by providing thorough, complete care to fewer patients than by superficially involving yourself with a lot of patients.

GROW. As you become more comfortable in the ED, challenge yourself to pick up one more patient than your prior shift, still being sure not to get overloaded. Set an alarm or timer for your history and physical exams to practice becoming more efficient — without cutting corners. For patients undergoing procedures, familiarize yourself with the steps of the process, the supplies needed, and express an interest in performing or assisting whenever possible. Lastly, recognize that managing a patient in septic shock will require more attention than some other patients, and that not carrying “more patients” does not reflect your effort or ability.

TALK TO YOUR TEAM. Check in with your supervisor at the start of every shift. Introduce yourself and identify expectations and responsibilities for each shift. Expectations may change from attending to attending, shift to shift, and it’s important to recognize these differences. Examples of these are: Should you assign yourself to the next patient or should you ask permission before assigning yourself to new patients? Should you present before or after writing your note? Are you responsible for writing your orders?

Lastly, communicate with the entire team (attendings, residents, nurses, consults, secretaries, transportation techs, etc.) respectfully and pleasantly. Learn names. Let them you are there and eager to be a part of patient care. This allows them to show you interesting cases, teach procedures, and be included throughout the course of your shift.

ASK QUESTIONS. If you are unsure about something, ask! Asking questions reflects an interest in learning and demonstrates that you are thinking about your patient’s presentation. Remember, we know you’re a medical student and you’re here to learn. It’s our responsibility to educate medical students, and most teaching departments work to foster learning. Of course, there is a balance — before asking a question, consider looking up the answer to your question and be ready to discuss possible management strategies. A good way to phrase this (and demonstrate self-motivation) is “I have a question regarding management of X. I’ve read that we can do Y, however, was wondering if that’s the appropriate course in the setting of...” Also, unless your question involves an emergent issue, certain times in the ED may not be appropriate for discussions and feedback (sign-outs, critical patients, etc.).

If you are unsure about something (how to call a consult, discharge a patient, etc.), ask your attending or team members. In general, we recommend asking residents first, as sometimes the attending is managing multiple other tasks.

ACE THE FINAL EXAM. Depending on your rotation site, you may take an exam created by that department or by a national organization. Be sure to inquire about what resources are recommended for preparation (readings, practice questions, etc.). Free and fee-based question banks are widely vailable.

Do some reading, flashcards, and practice questions each day to build your knowledge base and prepare for the exam.

ATTEND CONFERENCE. Many sites integrate this into your clerkship schedule. However, if not, ask if you can attend weekly resident conferences. Your interest will be noticed, and it will give you an opportunity to see what’s new in EM, get to know some of the residents, and see what your weekly educational experience would look like if you match at that program.

BE KIND. Think of your clerkship as a month-long interview, remembering that your interactions with everyone, from attendings and residents to ED staff to the residency coordinator, will be noted. Be unfailingly kind, courteous, and professional.

LOOK AHEAD. Clerkships are the perfect chance to build your professional network, not only by meeting attendings, residents, and administrators, but also by connecting with other students who are rotating with you — because they could be your fellow resident next year. Along the same lines, get to know the city where you’re rotating; can you see yourself living there? Finally, find out up front whether an interview will be offered at the end of your clerkship; this data is available in EMRA Match.

Remember that while you’re continually being graded during your clerkship, this is also your opportunity to evaluate the program. Do you like the atmosphere, the residents, the attendings, the opportunities? These rotations will be the basis for how you evaluate each and every program where you interview.

Demystifying the SLOE

Now, let’s look at the criteria you will be evaluated on from that dreaded (mysterious?) SLOE. Why is this important? Program directors have ranked SLOEs (and rotation grades) as some of the most important criteria when looking at selecting potential residents.2 Therefore, understanding the SLOE provides insight into how you will be formally evaluated.

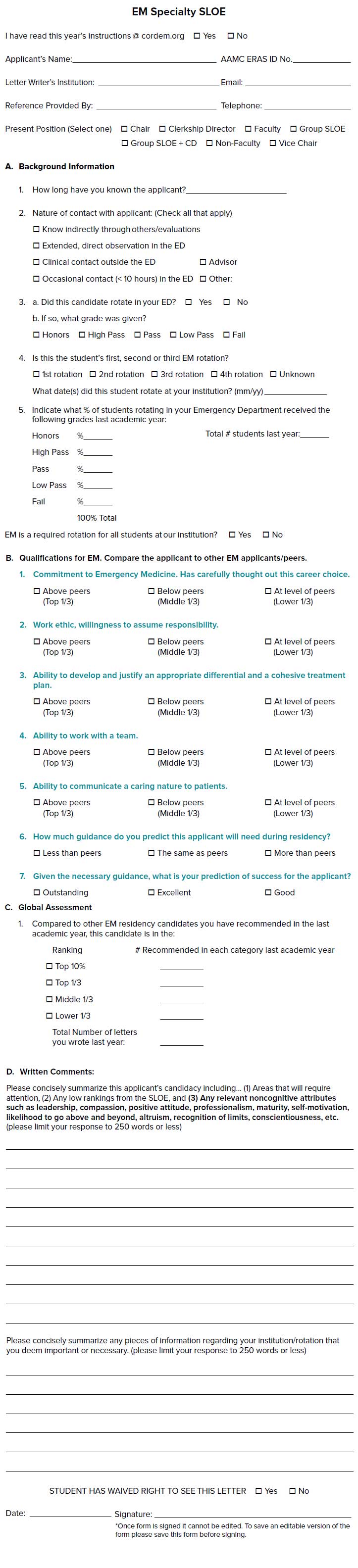

The SLOE has 4 sections: Background Information, Qualifications for EM, Global Assessment, and Written Comments. The first section includes background information on the applicant including which number EM rotation this is, what grade was given, and how the student’s grade compares to others in the past academic year. The “Qualifications for EM” reflect the areas you are likely be evaluated on throughout each shift. These 7 criteria broadly are: commitment to EM, work ethic, differential diagnosis and treatment development, teamwork, caring nature toward patients, potential future (residency) required guidance, and a prediction of success for applicants. These are answered in comparison to your peers. The third section is the “Global Assessment.” This has been cited as a significant predictor in rank order list position.3 This is where the letter writer is asked to rank the applicant in the top 10%, top third, middle third, or bottom third compared to other emergency medicine residency candidates. Further, the “Written Comments” section of the SLOE solicits writers to reflect on your non-cognitive attributes, such as self-motivation, altruism, attitude, maturity, compassion, etc. This part highlights areas that will require attention, addresses low rankings from the SLOE, and mentions the applicant’s strong attributes or characteristics. It is highly recommended that medical students review the SLOE form before beginning their emergency medicine rotation to understand the characteristics by which they will be judged.

At the end of the day, the SLOE provides readers insight into your perceived professional and personal strengths, and it enables writers to highlight both as they feel necessary.

Whom do I ask for my SLOE?

Most programs have a plan in place for rotators to obtain a SLOE. Some rotations will say who will handle the SLOE at the clerkship orientation, whereas others will have students formally ask. Typically you will ask the clerkship director to complete your SLOE. However, some clerkships will ask you to obtain a SLOE from the faculty who knows you best. If this is the case, try to identify a faculty member early on in the rotation, especially if your rotation is late in the cycle. Many academic departments are now creating a “departmental SLOE” — a jointly signed letter from the clerkship director, program director, and associate program directors.

Clarify the process by which you will obtain your SLOE on the first day of your rotation.4 Importantly, it is expected that you will have a SLOE from each site at which you rotated. Not having a SLOE will be perceived as a red flag and may require explanation if you are invited for an interview. An exception to this is rotations that are scheduled later in the application cycle. If you have already submitted 2 SLOEs and you are completing a third EM rotation later in the year (ie, December), you do not need to obtain a SLOE from this rotation.

IMG Students: Make it known to the medical student director very early on in your rotation, or even prior to starting, that you hope to obtain a SLOE from them.

FIGURE 6.2. Official CORD SLOE

End-of-Shift Feedback/Evaluations

While the SLOE is a summary evaluation of your performance for your entire rotation, it is crafted based upon the cumulative feedback/evaluations you receive for each individual shift. Students should determine who will be evaluating them at the end of each shift, will it be an attending, a senior resident, or both?

While you are being evaluated and graded continually by the faculty and upperlevel residents during your clerkship, you should not be a passive bystander. Seek feedback early and often — even if that means waiting for your supervising resident or attending to finish signing out (while being respectful of their time). Be prepared to explain what you think you did well, what you would do differently, and how you plan to improve on the next shift. Clear communication at the beginning of each shift also enables you to show that you are engaged with specific goals: for example, “Today my specific goal is to work on (insert X), and I’d love feedback on it.” At the end of the shift follow up on this goal and seek constructive criticism.

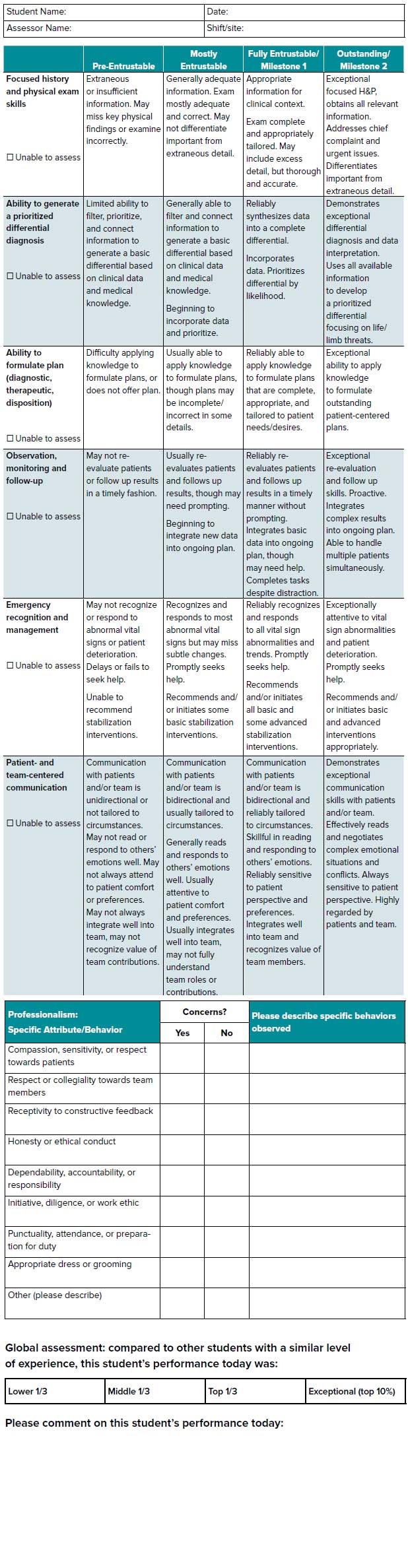

In addition to familiarizing yourself with the contents of the SLOE, you should also familiarize yourself with the end-of-shift evaluation tool that will be used to judge your performance. Many clerkships have adopted the “National Clinical Assessment Tool” to provide standardized evaluation across institutions, calculating a final grade by averaging NCAT-EM scores from 5 shifts.2 The group identified 6 clinical performance domains to evaluate, along with an assessment of your professionalism during a shift.2

FIGURE 6.3. National Clinical Assessment Tool

The Bottom Line

- Performing well on your EM rotation requires knowing the differential diagnosis for common chief complaints, being able to synthesize and succinctly present patients to your attending or supervising resident (including your plan), “owning” and re-evaluating your patients, and being a great team player and communicator.

- Ask for feedback! Familiarize yourself with the tools that will be used in your evaluation so you can focus on demonstrating behaviors that will give you a competitive SLOE and grade from your rotation.

- Make use of the Patient Presentations in Emergency Medicine instructional video to learn how to effectively and efficiently tell your patient’s story.

- Do not under any circumstances lie about the patient history you take or about an exam finding. Your supervisors know that you’re learning, and they don’t expect perfection. They do expect honesty — and it will take a long time, if ever, to earn back trust if you lie.