Anaphylaxis is under-recognized and undertreated.

This seems counterintuitive, as it’s hard to imagine the stereotypical anaphylaxis patient being difficult to diagnose. This is likely influenced by pop-culture portrayals of the classic anaphylaxis patient with respiratory distress, rash, and the TV physician who nails the diagnosis immediately. Anaphylaxis is also commonly discussed in the media, and many schools have policies to limit potential exposures. This highlights the prevalence of public awareness of the diagnosis.

In reality, anaphylaxis is much more complex than commonly portrayed.1,2,3

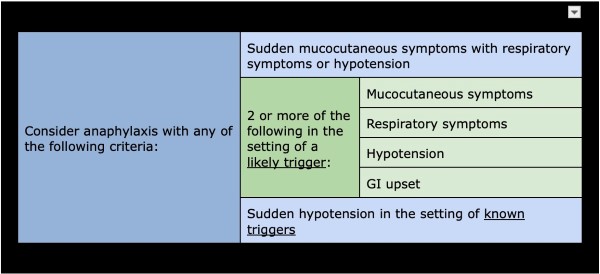

In 2004, a multidisciplinary group developed the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network (NIAID/FAAN) criteria to define anaphylaxis. This criteria has since been widely adopted and prospectively validated.2 A summary of the criteria is in Figure 1. To summarize for the emergency physician: If a patient has skin, GI, or respiratory symptoms or hypotension after a known or possible exposure, consider anaphylaxis.

Figure 1

Unsurprisingly, with such a broad definition, anaphylaxis can go unrecognized by health-care providers and is often undertreated, especially in children with predominantly GI symptoms.4,2 The severity of this presentation can vary widely, with loss of airway and hemodynamic collapse at the most severe end to the spectrum.

Case

“Code urgent, ED lobby” is called overhead, prompting half the department to rush to the lobby where a young man is found in a private vehicle, unconscious in the passenger seat. He is breathing spontaneously, but cannot be aroused; there is mild edema to his lips, but no audible stridor. He receives a dose of intranasal narcan as he’s being transitioned to a stretcher with minimal effect. The driver of the vehicle is frantic and crying, but mentions that he had antibiotics for his ear that he took earlier today. The patient is emergently transitioned back to a resuscitation bay.

He groans as the team brings him to the trauma bay, but otherwise has no change in mental status. On exam, he has bilateral breath sounds and is tachypneic without stridor or wheezing, has a palpable femoral pulse, and has equal, midside pupils. Additionally, he is noted to have mild edema of the lips with generalized diaphoresis, piloerection, and trackmarks. Initial blood pressure is 54/28, heart rate is 120, and oxygen saturation is 100% on 2L via nasal cannula. With the reported antibiotic exposure, therapeutic interventions pivot and the patient is given 0.3mg of intramuscular epinephrine, with improvement in blood pressure and mental status.

Eventually, this patient was able to provide further history, describing symptoms including lip swelling, pooling of secretions in his mouth, stridor with difficulty breathing, fatigue, and eventual loss of consciousness. He remained stable after his initial resuscitation in the emergency department. He was weaned off nasal cannula 9 hours after arrival. He received additional H1 and H2 blockers, as well as intravenous steroids and nebulized albuterol-ipratropium every 6 hours with marked improvement of his angioedema. At discharge, he was counseled extensively regarding avoidance of all medications in the penicillin class, and his allergy status was updated.

Developing a Differential, Initial Management

In patients presenting with a decreased level of consciousness, it is important to develop an appropriate differential diagnosis. Overdose of prescription medications, recreational drugs, or alcohol is high on the differential, especially in young patients. Inadequate perfusion of the brain secondary to hypotension covers a range of disease states including hemorrhage, sepsis, and arrhythmia. Other considerations include, but are not limited to, neurologic pathology like stroke or seizure, endocrine emergencies such as diabetic ketoacidosis or myxedema coma, and environmental exposures such as hypothermia and heat stroke. In many cases, the history and initial assessment will guide your evaluation toward one of these diagnoses.

Mainstays in Management

The mainstay management of anaphylaxis is early administration of epinephrine and supportive care, including management of the patient’s airway and hemodynamics.2 Administration of epinephrine in the prehospital setting decreases the likelihood of hospitalization,4 while delayed administration is linked in increased risk of mortality.3

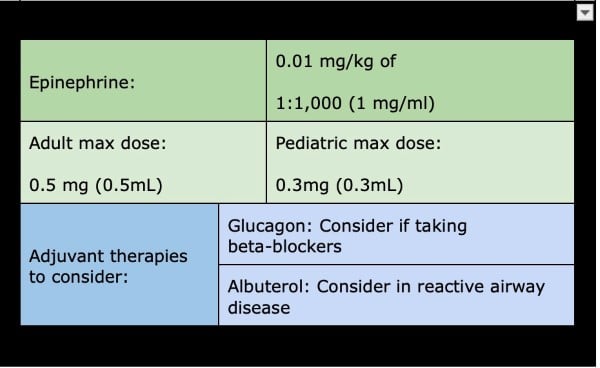

Epinephrine should be given intramuscularly at 0.01 mg/kg of 1:1,000 solution with a max dose of 0.3mg in children and 0.5 mg in adults.2 For patients with refractory symptoms despite repeated intramuscular doses, an intravenous epinephrine infusion should be considered.5

Epinephrine works by combating cardiovascular collapse by increasing chronicity of the heart and causing peripheral vasoconstriction; it also addresses airway compromise by triggering the relaxation of smooth muscles in the airways and attenuating the activation of mast cells, thereby decreasing airway edema.4

Supportive measures can include fluid resuscitation for hypotension, oxygen supplementation, and placement of a definitive airway.1,4 Glucagon may be considered in hypotensive patients taking beta-blockers, as it can increase heart rate and contractility independent of beta-adrenergic receptors,6 and inhaled beta-2 agonists may be considered in patients with reactive airway disease.4 However, determining their use will be on a case-by-case basis. See Figure 2.

Figure 2

While adjuvant medications such as antihistamines and glucocorticoids are often administered, they are unlikely to benefit in the acute phase. Evidence for their use is weak and largely based on expert consensus versus RCTs.4,1

The 2020 practice parameter update by the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology recommends against the use of glucocorticoids for the prevention of biphasic reactions,2 while the 2021 European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) describes glucocorticoids as potentially deleterious in children, but states that there is insufficient evidence regarding their utility for preventing biphasic reactions.1,7

Antihistamines, especially combined H1 and H2 blockers, can provide improvement of cutaneous symptoms. They have not been proven to address the life-threatening sequelae of anaphylaxis — angioedema and shock — or the prevention of biphasic reactions.1,4,8

Biphasic reactions occur in 1%-20% of patients presenting with anaphylaxis, which is why observation in the emergency department remains important and why patients should be counseled about this possibility, given reports of biphasic reactions as delayed as 78 hours after initial exposure. 2 With that being said, the amount of time necessary for observation remains a topic under investigation, and the length of observation will often vary by severity of reaction and patient factors. Features that increase likelihood of a biphasic reaction include severe reaction, wide pulse pressure, cutaneous symptoms, drug reactions in children, unclear trigger, and multiple doses of epinephrine.2 Patient factors that warrant prolonged monitoring include limited access to health care, history of severe asthma, and prior biphasic reaction.1

Anaphylaxis Airway Pearls

Some patients require establishment of a definitive airway and mechanical ventilation; however, airway edema increases the likelihood of a difficult airway. Many societies have recommended algorithms for addressing the difficult airway, and early recruitment of support is essential.9 This is not always possible, and providers may have to proceed on their own. Use of direct or indirect laryngoscopy with a bougie near at hand is a familiar technique that many physicians would choose to start with, while fiberoptic intubation, either orotracheally or nasotracheally, can be considered if a fiberoptic scope can be obtained within the necessary timeframe — that is, if it is in the department and the provider already knows how to use it.9 In adults and older children (5-12 years or older), depending on which reference is being used10, a surgical cricothyrotomy can be considered. In infants and younger children, or those on whom a surgical cricothyrotomy cannot be performed, a needle cricothyrotomy can be used instead. If using a needle cricothyrotomy, it is imperative to remember that this will provide oxygen, but will not adequately ventilate the patient and requires definitive airway due to worsening hypercarbia.10,11

Discharge Considerations

In up to 20% of patients, the causative agent is not identified4 and may represent either idiopathic anaphylaxis or the patient may not realize that they encountered a trigger. When a patient presents with anaphylaxis, it is important to provide close follow-up recommendations. Patients generally follow up with their primary care provider; however, they can also be offered follow-up with an allergist. This may be particularly beneficial for a patient with no identified trigger. In addition to outpatient follow-up, patients should be prescribed epinephrine IM and provided with counseling on recognizing anaphylaxis. Patients should be informed about the importance of early use of epinephrine and ensuring they have the means to activate EMS in case of possible exposure.4,1

Anaphylaxis is a true and potentially life-threatening emergency. Understanding that this condition has broader diagnostic criteria than are commonly recognized will help with early recognition and treatment. The mainstay of treatment is with IM epinephrine, as well as provision of appropriate supportive care. The patient must be monitored for biphasic reactions. Administration of common adjuvants has not been demonstrated to decrease the likelihood of recurrence. Ultimately, extended observation of high-risk patients and thorough counseling of all patients on discharge, as well as a prescription for epinephrine, remain important aspects of anaphylaxis management.

Key Points

- Early recognition of anaphylaxis, even in the absence of cutaneous symptoms, and early treatment with epinephrine is potentially life-saving.

- Know what difficult airway tools and resources you have available and how to use them.

- Adjuvant medications have not been proven to prevent biphasic reactions, but they can help with symptoms.

References

- Muraro A, Worm M, Alviani C, Cardona V, DunnGalvin A, Garvey LH, Riggioni C, de Silva D, Angier E, Arasi S, Bellou A, Beyer K, Bijlhout D, Bilò MB, Bindslev-Jensen C, Brockow K, Fernandez-Rivas M, Halken S, Jensen B, Khaleva E, Michaelis LJ, Oude Elberink HNG, Regent L, Sanchez A, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, Roberts G; European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Food Allergy, Anaphylaxis Guidelines Group. EAACI guidelines: Anaphylaxis (2021 update). Allergy. 2022 Feb;77(2):357-377. doi: 10.1111/all.15032. Epub 2021 Sep 1. PMID: 34343358.

- Shaker MS, Wallace DV, Golden DBK, et al. Anaphylaxis-a 2020 practice parameter update, systematic review, and Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(4):1082-1123. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2020.01.017

- Turner PJ, Jerschow E, Umasunthar T, Lin R, Campbell DE, Boyle RJ. Fatal Anaphylaxis: Mortality Rate and Risk Factors. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017 Sep-Oct;5(5):1169-1178. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.06.031. PMID: 28888247; PMCID: PMC5589409.

- Pflipsen MC, Vega Colon KM. Anaphylaxis: Recognition and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2020 Sep 15;102(6):355-362. PMID: 32931210.

- Fujizuka K, Nakamura M, Tamura J, Kawai-Kowase K. Comparison of the efficacy of continuous intravenous infusion versus intramuscular injection of epinephrine for initial anaphylaxis treatment. Acute Med Surg. 2022;9(1):e790. Published 2022 Oct 20. doi:10.1002/ams2.790

- Peterson CD, Leeder JS, Sterner S. Glucagon therapy for beta-blocker overdose. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1984;18(5):394-398. doi:10.1177/106002808401800507

- Sheikh A, Ten Broek V, Brown SG, Simons FE. H1-antihistamines for the treatment of anaphylaxis: Cochrane systematic review. Allergy. 2007;62(8):830-837. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01435.x

- Lin RY, Curry A, Pesola GR, et al. Improved outcomes in patients with acute allergic syndromes who are treated with combined H1 and H2 antagonists. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36(5):462-468. doi:10.1067/mem.2000.109445

- Kollmeier BR, Boyette LC, Beecham GB, et al. Difficult Airway. [Updated 2022 Jul 11]. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- McKenna, Peter, et al. Cricothyrotomy. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf.

- Mittal, Manoj K. “Needle Cricothyroidotomy with Percutaneous Transtracheal Ventilation.” 2022.