Ch 15. Traveler Health and Weallness

Introduction

With hundreds of destinations around the world that you can travel to, it is impossible and imprudent to try to describe the variety of potential illnesses that you might encounter. Not all illnesses are preventable, but with appropriate precautions, many are avoidable. Having an understanding of the health risks and setting of the destination is invaluable for preparation. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) offers an excellent resource on Traveler's Health with country-specific recommendations. They also offer an app version.

The following are health and safety recommendations that provide additional considerations and resources specifically for travel, but do not ignore or suspend normal practices or health advice. Many people who travel abroad may be more worried about contracting a rare infectious disease, but accidents or injuries are the leading cause of death in travelers. Be aware of your surroundings and use helmets, seat belts, and drive at reasonable speeds. The Association of International Road Travel provides country-specific risks.

Additionally, the CDC website offers information on other personal health-related resources including, but not limited to topics such as pregnancy, motion sickness, altitude sickness, extreme temperatures, deep vein thrombosis, and mental health.

If you have a chronic illness, plan to carry medications that will be required for the duration of trip and leave them in the original container. With some medications, verify that they are not illegal in the country you are entering (e.g. narcotics). Carry a letter from the prescriber that states your medical condition and medications prescribed. Be wary of counterfeit drugs or the unavailability of specific medications in some countries.

Vaccinations

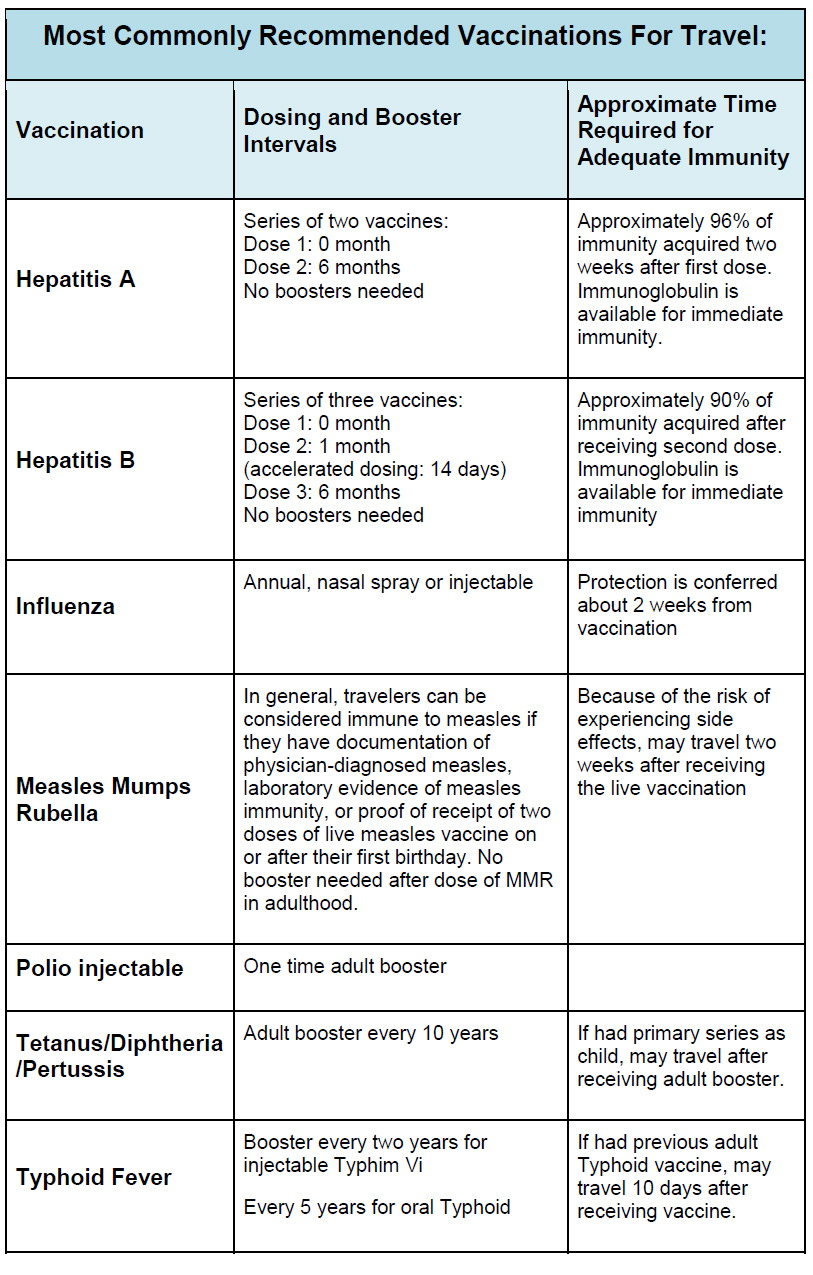

Vaccinations are an important part of any pre-travel preparation. Routine vaccinations should be up-to-date prior to any travel and should include immunization against measles, mumps, rubella, polio, varicella, meningococcal spp, hepatitis A and B, human papilloma virus, influenza, tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis depending on the age of the traveler. The Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention (CDC) publish routine vaccination schedules. Any traveler should ensure compliance with these prior to departure.1 Additional vaccines might also be recommended depending on your travel destination. CDC has country specific information available online and is an invaluable resource.

Importantly, proof of certain vaccinations, e.g. yellow fever and meningococcus, may be required by immigration in specific countries. Other vaccines, e.g. for cholera, have been developed but are not currently available in the United States. The recipient of any vaccine should be counseled regarding the risks and benefits of receiving the vaccine. An analysis of the recipient’s risk tolerance should also factor into decision-making, as should specific risk associated with the traveler’s itinerary. In addition, vaccinations do not negate the need for other protective measures.

Hepatitis A

Infection with Hepatitis A is often self-limited, although, fulminant hepatitis with coagulopathy and encephalopathy can occur.4 The vaccine is composed of a live inactivated virus. Two doses are recommended per CDC. The first dose can be given after one year of age.5 The booster is recommended 6-18 months later, although excellent protection occurs with just one dose. Those with cirrhosis are more susceptible to the

severe form and must be vaccinated. Immunoglobulin is recommended for immunocompromised individuals or travelers over 40 years of age who are not previously immunized and will provide 3-6 months of protection.5

Hepatitis B

Most people who contract HBV are asymptomatic and become chronic carriers. Cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma are serious complications.4 Risk is increased with sexual contact, sharing contaminated needles, receiving blood products, adventure travel, and in health care workers.6 Risk is more behavior driven than destination specific. The vaccine is also an inactivated live virus. A 3-dose schedule will provide up to 90% protection.6

Typhoid

Salmonella typhi is the causative agent of typhoid fever, and is an important cause of waterborne illness in resource-poor settings. Complications of typhoid fever include bowel perforation, severe GI bleed, meningitis, and hepatitis. A chronic carrier state can lead to cholangiocarcinoma.4 The vaccine is recommended for travel to Africa, SE Asia, India, South America.2 Transmission is fecal-oral through ingesting contaminated food or water. There are two vaccines available. Both only provide 50-70% protection and can be overwhelmed by a high burden of Salmonella typhi. There is no protection for Salmonella paratyphi. The live-attenuated oral vaccine (Ty21a) provides up to 7 years of protection and can be given to children over six years old. It requires taking a dose every other day for four doses.7 It does require refrigeration and the live bacteria are sensitive to antibiotics if the recipient is taking them concurrently. The purified Vi-polysaccharide single dose injection provides up to 3 years protection and can be given to children 2 years or older.7 The manufacturers recommend repeating the injectable form every 2 years and the oral form every 5 years if there is continued exposure.7

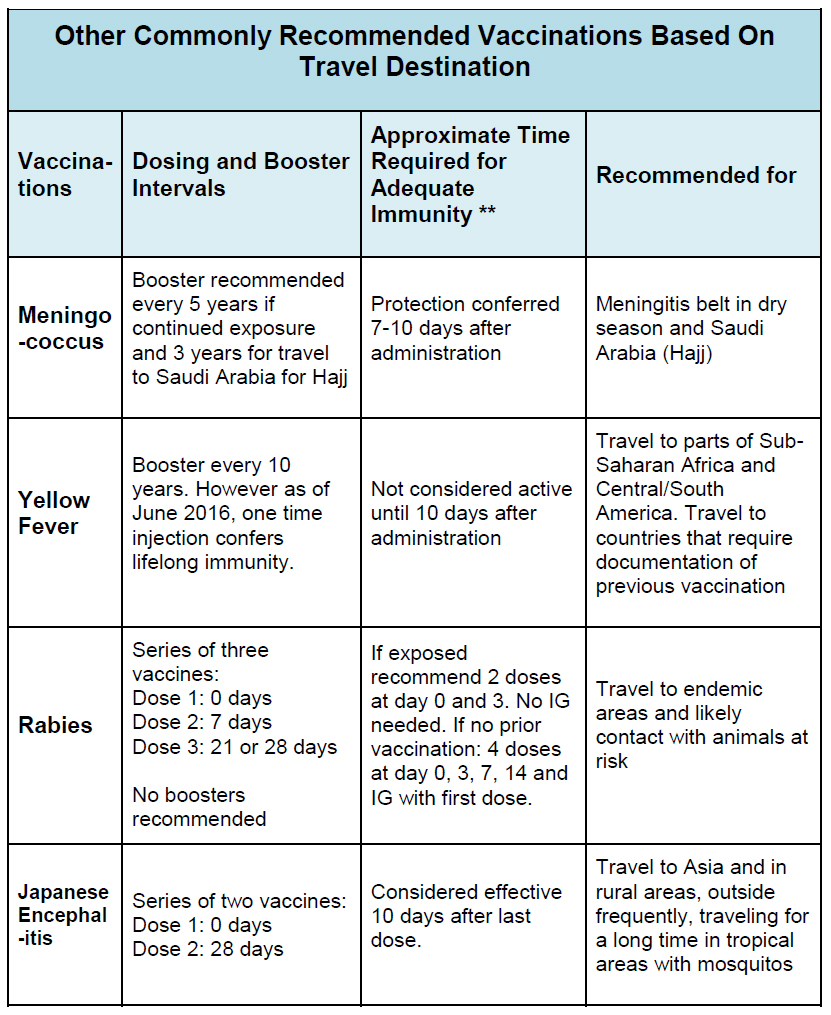

Japanese Encephalitis

JE has high morbidity and mortality without pre-exposure prophylaxis. This is a mosquito-borne flavivirus prevalent in SE Asia. Ten to fifteen thousand people die every year and many more are left with permanent neurological disability.4 The vaccine is expensive. The primary series requires vaccinations at 0 and 28 days. For short-term travelers (<1 month) to endemic countries, it is recommended only if going to rural areas or doing extensive outdoor activities. It is recommended for anyone going to endemic areas long-term, defined as >1 month.10

Meningococcus

The “Meningitis Belt” runs across equatorial Africa, especially during the dry season, December through June. Health care workers should be vaccinated if going to any of these countries.11 It is also required for travelers going to Saudi Arabia to the Hajj and recommended for all travelers going to endemic areas during the dry season.11 In the U.S., all adolescents from age 11 now receive it as part of their routine series, however, a booster is recommended at 5 years.12

Rabies

Rabies has one of the highest case fatality rates in the world. It is highly endemic in Africa, Asia and parts of Latin America. Rabies is uncommon in travelers, however animal bites are relatively common.8 Finding reliable post-exposure prophylaxis when traveling can be difficult to access, expensive and there are issues with counterfeits. Therefore it is recommended to have pre-exposure prophylaxis before going to endemic areas, especially if one has an occupational risk of exposure, an extended stay, outdoor travel plans or is traveling with children.9 The pre-exposure vaccine series involves 3 doses of 1.0 mL given IM (0,7,21-28 days). Once pre-vaccinated, no booster is needed and you are covered for life. If bitten, 2 post-exposure vaccine doses are required. If you have not had pre-exposure prophylaxis, treatment requires Rabies IG and 4 doses of vaccine (0,3,7,14 days) per Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) guidelines.9

Yellow Fever

Most commonly a flu-like illness that resolves, however 15% of patients will develop severe disease including hemorrhagic fever, fulminant hepatitis and renal failure. If severe, mortality approaches 50%.4 There are an estimated 30,000 deaths per year mainly in the South American Amazon and Africa.13 The vaccine is live-attenuated and thus contraindicated in patients with primary immunodeficiencies, transplant recipients, those taking immunomodulatory drugs and those with thymic disorders.13 If entry into a country requires a YF card (ICVP card), the vaccine must be given at least 10 days prior to entry. If you have a contraindication to vaccination, or you and your travel health care specialist decide that the risks of vaccination outweigh the benefits, you may get the vaccination card, date it and sign it with “NI” written on it to indicate “Not Indicated”. This will avoid unnecessary hassle at the border. WHO in 2013 stated that one dose is good for life however countries may still require the 10 year booster as part of regulations.14 The vaccine can be given at one year of age. There have been 32 vaccine-related deaths (out of approximately 50 million doses). The very rare and severe adverse effects are viscerotropic disease and meningoencephalitis in young infants. As such it should only be given if needed based on CDC guidelines.13

Other Vaccines

There are other vaccines that have been developed but are not currently available for commercial use in the U.S., including Tick-borne Encephalitis (TBE), Plague, Smallpox, Cholera and Anthrax. Decision to start these vaccines should be made with your personal physician and/or the organization you are working with.

Travel Medications

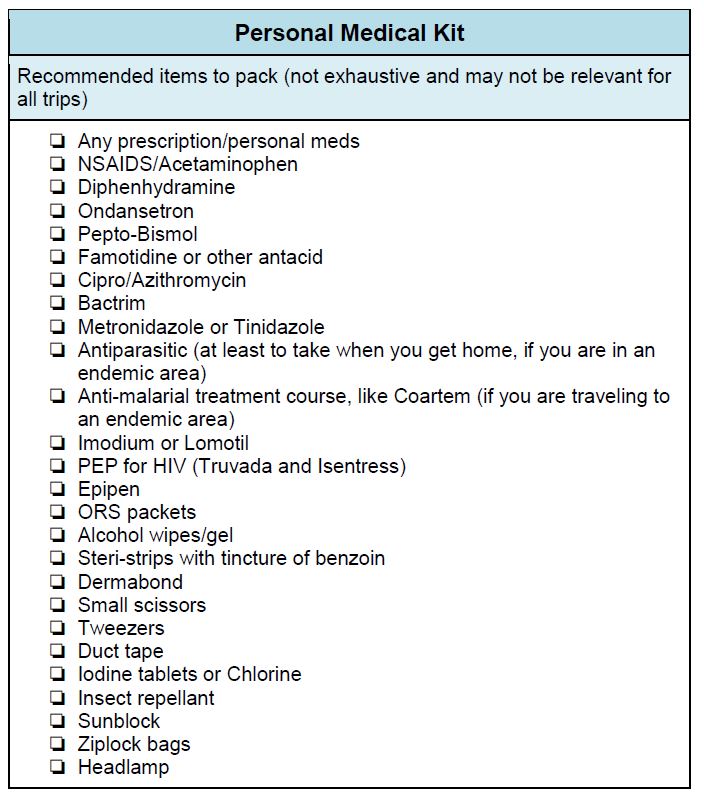

A priority in any medical trip is the health of you as the provider. An understanding of diseases common to travelers is essential for determining which medications are necessary for prevention and treatment. Without appropriate preparation, your trip of a lifetime might be tragically cut short by an illness that is otherwise preventable or easily treated.

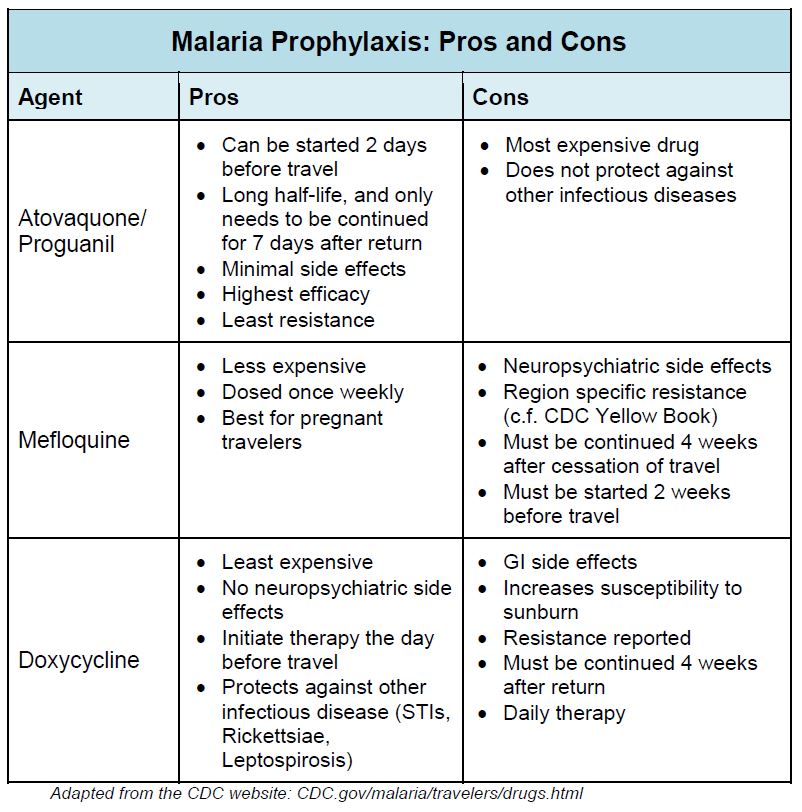

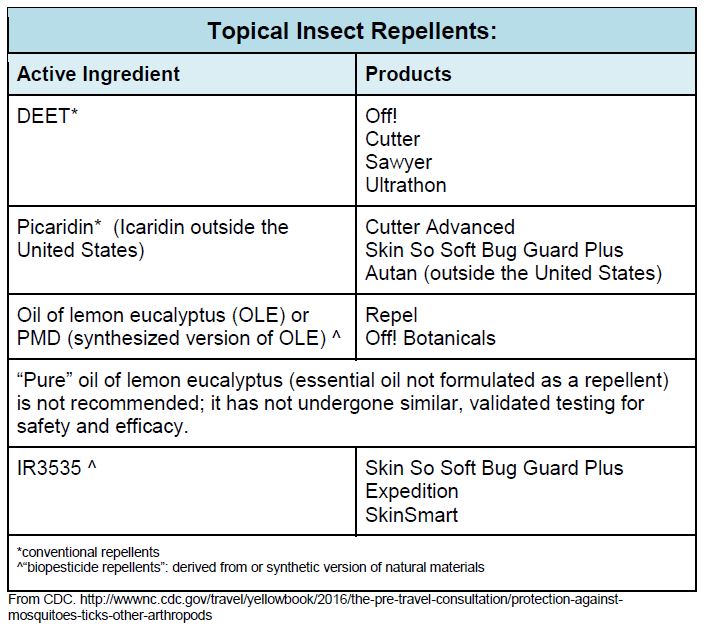

Malaria Prevention

Malaria is the most common cause of fever in the returned traveler in cases where an etiology for systemic febrile illness is identified.1 It is a parasitic infection transmitted by female Anopheles mosquitoes and is endemic throughout the tropical and subtropical regions of the world. While chemoprophylaxis is highly effective against the transmission of malaria, the first step in prevention is avoiding exposure to mosquito bites. Permethrin-impregnated clothing, DEET containing skin spray, and chemically-treated bed nets are essential to the prevention of malaria and other mosquito-borne illnesses.

Despite meticulous care to avoid mosquito bites, they are inevitable, and malaria chemoprophylaxis is of paramount importance for travelers to endemic regions. Choosing the appropriate medication depends both on the traveler and the destination. Detailed, country-specific resistance patterns are accessible via an online resource published by the CDC called the Yellow Book.

Atovaquone-proguanil (Malarone) is the drug of choice with regard to efficacy, resistance, and convenience. Mefloquine and Malarone have similar, near 100% efficacy when used as prescribed. However, due to its neuropsychiatric side effects, mefloquine therapy is often discontinued prematurely.2 Doxycycline, another efficacious chemoprophylactic agent,3 is the least expensive option, and can protect against other common infectious diseases like leptospirosis, Ricketssiae and some sexually transmitted diseases. There is some emerging resistance to doxycycline, however, and its side effect profile may also inhibit compliance with the full necessary course. It is useful for you if you are on a budget, or an adventure traveler who will be exposed to water or rural areas.

Regardless of your choice of anti-malarial agent, compliance with initiation, dosing and duration of therapy is crucial in preventing infection with plasmodium species. Most “treatment failures” of malarial prophylaxis occur due to noncompliance, missed doses or self-discontinuation. You should be aware of the potential side effects of the medicine you plan to take.

Diarrheal Illness

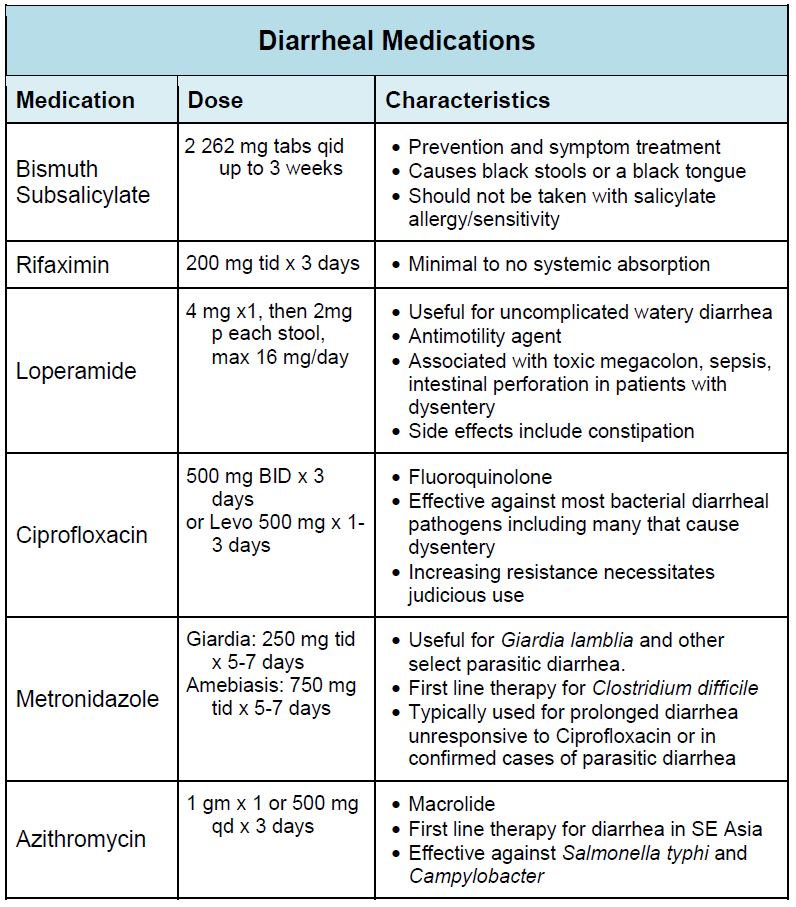

Diarrheal illness is the most common syndrome affecting travelers to the developing world. Traveler’s diarrhea (TD) is a syndrome with many causative agents including bacteria (90%), viruses, and parasites,1 and may occur in as many as 70% of travelers.4 Since bacteria found in food and undertreated water make up majority of cases, medical therapy is directed primarily at these agents. Medications for traveler’s diarrhea fall into two categories: prevention and treatment.

Prevention

The mainstay of prophylaxis should be water and food hygiene. Medications cannot replace good dietary decisions, and boiling water is far more effective at killing the myriad of causative organisms than any prescription. Candidates for chemoprophylaxis should be carefully selected, since effective agents have significant side effects, and may be poorly tolerated. Prophylactic medications are best for short trips and travelers who cannot afford a day or two of diarrhea (VIPs, athletes, etc.). Two drugs have been shown to decrease the incidence of traveler’s diarrhea are bismuth subsalicylate (BSS) and rifaximin. BSS is a salicylate-containing compound available in pill and liquid form, but must be dosed 4 times daily as it has short term antimicrobial effects.5 While it is efficacious in preventing up to 90% of traveler’s diarrhea, BSS has many side effects as listed in Table 2.6 Rifaximin, an antibiotic that is not absorbed through the gut, has also been shown to be effective in reducing traveler’s diarrhea. Its efficacy is limited to non-invasive bacterial pathogens.7 Moreover, its long-term side effects due to changes in gut flora are poorly understood and most experts recommend against using this medication. “Probiotics” such as lactobacillus formulations remain controversial.4 Previously effective antibiotics (e.g. Bactrim and Doxycycline) are no longer recommended due to high resistance profiles.6

Treatment

Whereas prophylaxis for traveler’s diarrhea is poorly studied and should be limited to special populations, the incidence and morbidity associated with TD necessitate most travelers to have a treatment plan. The main causative organisms include bacteria (E. coli, Shigella, Salmonella, Campylobacter) and protozoa (Giardia and others). Many cases of traveler’s diarrhea are self-limited with minimal morbidity. Travelers with less than 3 stools per 8 hours, who are well-appearing without signs of dehydration or dysentery likely require no therapy. For those with diarrhea of longer duration, but without signs of dysentery (fever, severe cramping, bloody stool) may benefit from antimotility agents such as loperamide. Due to concerns for intestinal complications, loperamide and other antimotility agents are not recommended in patients with any signs of dysentery.3 Patients with severe or prolonged diarrhea (in our opinion greater than 2 days), or with dysentery while traveling should be treated with an antimicrobial agent. Ciprofloxacin remains effective against most bacterial diarrheal infections and is recommended by most experts as first line antibacterial therapy due to its price.6 However, there is increasing resistance among strains of Salmonella typhi (the causative agent of typhoid fever) and Campylobacter in the Middle East and much of Asia.8 If you travel to these regions, consider the use of Azithromycin. Ciprofloxacin is also not effective against amoebic or other parasitic dysentery. Metronidazole is first line therapy for giardiasis and is a cheap medication that is a reasonable inclusion in the traveler’s medication kit. Most protozoan and other parasitic infections have longer incubation periods (1-2 weeks), compared to bacteria (2-5 days). Thus the need for metronidazole as a treatment modality while traveling is limited to longer duration trips and prolonged diarrheal cases.

You should seek prompt medical care for severe diarrheal cases with marked dehydration, prolonged high fevers, bloody diarrhea, or abdominal pain. IV fluids or more intensive antibacterial therapy may be required for severe infections or infections with invasive or toxigenic pathogens.

Other Medications

You should have other medications available for other purposes as well. Prescription medications for pre-existing conditions should be continued. Consider drug-drug interactions between anti-malarials or anti-diarrheals and prescription medications, especially antidepressants or other psychiatric medications.

Sleep interruption can cause significant morbidity in travelers. Jet lag, a new environment, and the stress of the practice of medicine in an unfamiliar context all contribute to poor sleep. Good sleep hygiene should be practiced when possible. However, it is common for the international traveler to require pharmacological help. Antihistamines like diphenhydramine are useful as sleep aids and are doubly useful for unexpected allergen exposures. Zolpidem (Ambien) can also be used if there are no contraindications, but it is best to have tested it prior to any trip as it can be associated with significant side effects. The use of benzodiazepines or alcohol as sleep aids, although common, is associated with the risk of dependence and impaired decision-making and should be avoided.

When you travel you often endure long periods of inactivity during transport, restricted water intake, and changes in diet. Thus, in addition to infectious diarrhea, you are also at risk for constipation. Stool softeners such as docusate sodium can prevent the discomfort of constipation. Adequate clean water intake is always encouraged. Additionally anti-emetics like ondansetron may be considered, as nausea and vomiting are common and can limit antimalarial compliance.

Common over-the-counter medications may be limited in low-resource settings. Include commonly used medications such as ibuprofen, acetaminophen and antihistamines for treatment of mild illnesses in your medical kit. If you have a history of anaphylaxis, bring at least one injectable unit of epinephrine in the event of an episode, as this may not be available where you travel to.

If you will be working in a clinical setting and are at risk for HIV exposure, prompt post-exposure prophylaxis is essential. The current recommendation for HIV post-exposure prophylaxis is tenofovir + emtricitabine (Truvada) once a day plus raltegravir (Isentress) twice a day for 28 days as the preferred initial PEP regimen because of excellent tolerability, proven potency in established HIV infection, and ease of administration.9

Diet and Hygiene

In addition to vaccinations and medications, several practices and precautions can minimize exposure to potential illnesses and conditions.

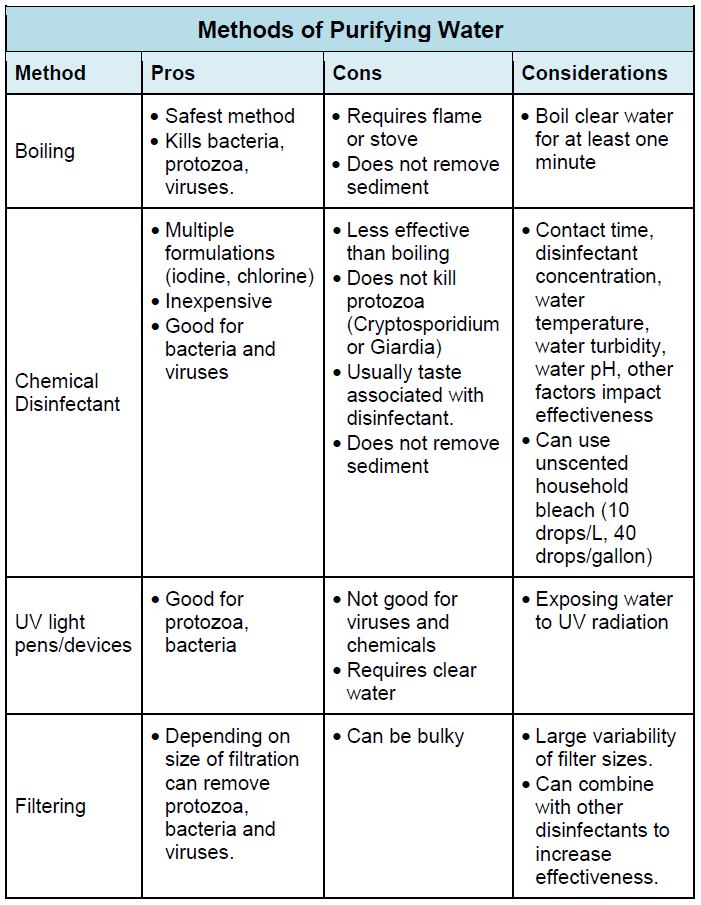

Hand Hygiene and Water

Hand hygiene is important to minimize the spread of infectious agents. Bring alcohol gel or wipes when clean water is not available. Clean water is sometimes a limited commodity. If clean water is not available, there are several ways to purify tap or natural water. The method used will depend on location and available resources and time.

If you do get sick and do not have rehydration salts available (you should ideally bring some with you), you can make your own basic solution. In one liter of water, dissolve roughly one tablespoon of table sugar/honey/corn syrup and a half a teaspoon of table salt. Check out WHO’s published (2013) formulation for oral rehydration salts.

Food

Without access to your normal food routines, diets often times need to be adapted to the location and environment you travel to. While some people are flexible and adventurous and “eat as locals do”, there are food and food safety considerations every traveler should keep in mind.

If you can’t “cook it, wash it, peel it, forget it”. Consume cooked food that is served hot, fruits and vegetables that you have peeled or have been rinsed in clean water, and pasteurized dairy. Avoid beverages with ice (as it is usually made from tap water; at a minimum, ask how ice is prepared). CDC has a downloadable app with country-specific guidance called “Can I Eat This” .

When eating out, be wary of street vendors. Be sure dishes are served hot. Look at the condition of the cart or kiosk before ordering. Is it clean and well kept? Is it busy? The fewer the customers, the longer the food may sit before being served and the quicker it may make you sick. Eat at your own risk.

Same thing with restaurants: go where the people are. Busy restaurants typically serve fresher, cleaner, and safer food. Apps like Yelp or TripAdvisor may help. Regardless, ask that food is cooked well-done. It is also a good idea to have a phrasebook handy to help translate items on the menu. Again, eat at your own risk.

Always remember to wash your hands before you eat and to use “safe” water not only for your hands, but also for any foods that you might prepare yourself.

Other Considerations:

- Consider the cultural diet of the region of travel. There may be food customs that are unfamiliar or off-putting. Some diets may not be compatible with certain personal dietary practices. In cases like these, it is best to be honest and politely decline.

- Vegetarians have no issue if the staple diet is predominantly vegetable based. However, vegetarians can still live and work in rural villages where meat is a main staple. It typically requires advanced planning and an ability or means to communicate your dietary restriction so as not offend the local community especially if they cook a meal.

- Comfort foods and protein bars or other non-perishable snacks are good supplements to pack in places where nutrient rich foods or the variety of foods is limited. In addition, they can be something to share with local colleagues as a cultural exchange.

Drugs and Alcohol Use

Depending on the country and setting in which you are working, drugs or alcohol use may be inappropriate. In some regions of the world, drinking may be illegal, religiously offensive, or considered provocative or suggestive behavior. Check with your host or host institution of practices and any illegality of certain substances. Some countries carry stiff penalties for possession or use of drugs that can include imprisonment, hard labor or even the penalty of death.

Clothing and Protection From the Elements

While vaccinations can protect from certain vector-borne diseases, efficacy can depend on multiple factors and there are other vector-borne diseases for which there are no effective vaccines. Therefore, in areas where arthropod bites are of concern, other measures need to be used to prevent exposure. Ideally, clothing that covers exposed skin is preferable. However, where not possible or oppressive, the use of repellents and avoidance of peak times of day when the insects are most active is recommended.

General recommendations:

- Wear long-sleeved shirts, long pants, and socks.

- Treat clothing with permethrin or purchase pretreated clothing.

- Apply lotion, liquid, or spray repellent to exposed skin.

- For mosquitoes:

- Dengue, yellow fever, and chikungunya vector mosquitoes bite mainly from dawn to dusk.

- Malaria, West Nile, and Japanese encephalitis vector mosquitoes bite mainly from dusk to dawn.

- Use common sense. Reapply repellents as protection wanes and mosquitoes start to bite.

- For ticks:

- Check yourself daily (your entire body) and remove attached ticks promptly.

Also, be sure to use sunscreen or some form of protection from sun exposure. For weather extremes, be sure to bring multiple layers and clothing that either cleans or dries readily.

Wellness

Well-being and psychosocial health during travel is just as important as any physical illness. Loneliness and homesickness especially for extended trips are not unusual. Establishing a plan and a system to stay in contact with friends and family back home prior to leaving is feasible even in difficult environments. Many modes of communication are now available in most countries: email, prepaid phone cards, cell phones, and communication via wireless apps. Even planned sporadic or intermittent contact can help alleviate feelings of being alone.

Homesickness is a natural feeling in foreign environments. The best way to alleviate homesickness is often to dive into the experience. The more you are having fun and involved in your experience, the less time you spend feeling homesick. Establishing a trusted contact person either in the host country and/or back home that you can confide in is also important. This is someone who you should feel comfortable sharing your feelings and issues. Often, just knowing that there is someone you can contact can help alleviate loneliness or homesickness.

Not having privacy, personal space, or time to yourself can both exacerbate feeling alone and lead to the sensation of suffocation or being trapped. Most people in your group will probably feel the same way at some point during the trip. Establishing some boundaries explicitly or virtually is useful. Making plans with fellow colleagues to explore the area and to specifically spend time with each other outside of your living environment can be a way to establish some boundaries. Be sure to take time for yourself. Bring a leisure book or something else that is small and that you enjoy doing (a sketch pad to draw, a journal, etc.).

Easing into new environments can be overwhelming also. Bringing mementos that remind you of home can help ease this. Pictures of family and friends are good reminders of home, but also ways to allow people who you meet or are staying with to get to know you. Comfort foods, like a jar of peanut butter, or your favorite non-perishable snacks from home can help ease any culture shock with new foods.

Post trip

International trips can be stressful. Reverse “culture shock” is not uncommon. Transitioning back to civilian life and the environment that you live and work in at home may be difficult. If possible, schedule a layover stay of at least 1-2 days in a location that is a departure from the environment in which you were working and is a break from your “normal” life. International trips are often harder work and associated with different types of stress. Some rest and relaxation is warranted.

If possible, do not schedule a clinical work shift on the day or the day after you return. Travel, due to time change, and travel itself is draining. Medical equipment and luggage should be unpacked promptly. Disinfection of luggage, clothing, and equipment may be necessary to prevent contamination and/or to minimize risk of accidently transported vectors.

In addition, when you travel you may get sick after arrival back home. Incorporating recovery time is ideal. Remember that many chemoprophylactic medications for malaria require you to take medications several days and weeks after return to be effective.

References (Medications)

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC - Vaccines - Immunization Schedules main page. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Destinations | Travelers' Health | CDC. Retrieved from http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/list

- Gershman, M., et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Travel Vaccines & Malaria Information, by Country - Chapter 3 - 2014 Yellow Book | Travelers' Health | CDC. Retrieved from http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2014/chapter-3-infectious-diseases-related-to-travel/travel-vaccines-and-malaria-information-by-country

- Guerrant, R.L., Walker, D.H., & Weller, P.F. (2006). Tropical Infectious Diseases: Principles, Pathogens, & Practices. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingston.

- Update: Prevention of Hepatitis A After Exposure to Hepatitis A Virus and in International Travelers. Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). (2007, October 19). Retrieved May 15, 2015, from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5641a3.htm

- A Comprehensive Immunization Strategy to Eliminate Transmission of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in the United States Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Part II: Immunization of Adults. (2006, December 8). Retrieved May 15, 2015, from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5516a1.htm

- Updated Recommendations for the Use of Typhoid Vaccine — Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, United States, 2015. (2015, March 27) Retrieved May 15, 2015, from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6411a4.htm

- Phanuphak P. et al. Should travelers in rabies endemic areas receive pre-exposure rabies immunization? (1994). Ann Med Interne (Paris), 145(6), 409-11. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Ann Med Interne (Paris) 145:409

- Human rabies prevention United States, 2008: recommendations of the ACIP. (2008, May 23) MMWR Recomm. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18496505

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014, January 24). Retrieved May 15, 2015, from http://www.cdc.gov/japaneseencephalitis/vaccine/index.html

- Meningococcal Meningitis. (n.d.). Retrieved May 15, 2015, from https://www.iamat.org/risks/meningococcal-meningitis

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014, April 1). Retrieved May 15, 2015, from http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd-vac/mening/who-vaccinate.htm

- Yellow Fever Vaccine: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). (2010, July 30). Retrieved May 15, 2015, from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5907a1.htm

- Yellow fever vaccination booster not needed. Retrieved May 15, 2015, from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2013/yellow_fever_20130517/en/