Ch 11. Fellowships

Introduction

This chapter is a beginner’s guide to International Emergency Medicine Fellowship (can also be referred to as Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship, but we will refer to them as IEM fellowships here, as this is still the name associated with most fellowship programs) in the United States. We interviewed 16 fellowship directors either on the phone or in person and asked them a similar set of questions. The responses were as varied as the programs, however there was also a large amount of consensus. We share with you their answers on whether or not a fellowship is right for you, how to select the one that is right for you, and what fellowship directors are looking for. You will also learn about application and interview process from those that just went through it. Before we get to that, however, let’s talk some facts.

Some Starting Information

IEM fellowships have grown substantially over the past 15 years. Originally there was no consensus about what constituted an appropriate fellowship, and much work has been done to try and structure these fellowships to maximize the benefit to the fellows. Today, there are around 30 nationally recognized fellowships in the United States. Not every fellowship takes a fellow every year, but the majority takes 1 each year and many take two. Most fellowships are 2 years, and most offer an advanced degree such as an MPH, DTMH (Degree in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene), MSGH (Masters of Science in Global Health), or MBA. If you have already completed an advanced degree, some programs will allow you to complete just 1 year. The majority of applicants come straight out of residency, and all applicants must be EM board eligible by the time that they will start their fellowship. Each fellowship program is different, both in its concentration and the personality with which it approaches that concentration(s). Broadly, most fellowships focus primarily on one of the following.

- Emergency medicine development (Residency building, EM skills training)

- Acute Care in Resource Limited Settings/Capacity Building

- Disaster Relief/Humanitarian Aid

The Core Elements

Fellowship training is further broken down into the “7 Core Curricular Elements” that are believed to constitute adequate fellowship training in GEM. These were laid out in a paper published in 2008 by Bayram et al1. It is considered by most directors that a fellowship incorporate as many of these as possible, and most fellowships will normally include several of these core elements.

- EM systems development

- Humanitarian Relief

- Disaster Management

- Public Health

- Travel and Field Medicine

- Program Administration

- Academic skills

Do I need to do a Fellowship?

Well it all depends on what your interests are. Most basically, you do NOT have to do a fellowship to work internationally. For those interested in international clinical work, an IEM fellowship is most likely not necessary. The purpose of IEM fellowship is to train leaders in international/global emergency medicine, policy makers, systems builders, researchers, and those people who wish to dedicate a large portion of their life to the specialty. If clinical or mission work is what you seek, there are other ways to accomplish this that will not require you to give up as much as $500,000 over two years to complete a fellowship (assuming a high-paying community job instead of the fellowship). These other options are discussed in Chapter 13.

When deciding whether to do a fellowship, ask yourself WHY you want a fellowship: what do you wish to gain from it? Our interviewees offered two different decision-making paradigms, both of which agree that the more time you wish to dedicate to GEM, the more likely you are to benefit from a fellowship.

Paradigm #1 – Utilitarian

- As one director put it, there are three things that fellowship offers: experience, mentorship, and skills development. If you need these then fellowship may be the place for you. Think of it as a one stop shop for GEM goodness. However, if you have 2 of these 3 then fellowship may not be beneficial enough for you and there are probably easier ways to gain whichever attribute is lacking.

- Experience/Exposure: Fellowship places you into the world of GEM, and to the people and organizations that are shaping the international health world. It puts you face-to-face with the processes, challenges, and hardships inherent in the world of GEM: international research, program development, and education. For those not doing fellowship, it takes years to gain enough experience to reach a place where they will be surrounded by the world of GEM in a way that they can learn from it. In a fellowship you can learn these things in much less time. In addition, fellowship can offer you a larger breadth of exposure. This is a good option if you’re not sure which part of GEM interests you the most.

- Mentorship/Networking: Experience can only take you so far. Mentorship allows you to gain experience in GEM while being in an environment that allows you to benefit maximally from those experiences. By placing yourself around people that are more experienced, you benefit from the knowledge generated before you got there. In addition, mentors can put you into contact with people that you would have never had access to without them, and lend you credibility that you cannot get from a CV. Finally, the people that you meet and have contact with during your fellowship will become your network of people to reach out to for projects, advice, and collaboration.

- Skills Development: Did you learn everything you needed to know in residency? Of course not. The types of skills that are required in GEM are as varied as those that are in it. Only you can determine which skills you want to have, however here are some things to think about:

- Public Health Skills/Epidemiology: An MPH degree teaches you about health on a large scale. This skill can be invaluable on the global sphere where it is often public health interventions rather than brilliant diagnostic skills that make the largest impact.

- Research Skills: How do you create a focused needs assessment? How do you ensure a quality homogenous chart review? How do you talk to an IRB in India? These are skills that will benefit you.

- Education Skills: How do you teach a physician in Kenya about ATLS? How do you educate residents in Cambodia? Learn from those that do.

- Program development skills/Health systems: What does it take to set up an EMS system in Panama? Can you design a program for combating maternal mortality in Slovakia? What do you do to help out with an earthquake in Nepal?

- Clinical Skills: How do you treat typhoid? What do you do about sepsis when you have only limited antibiotics and no IV fluids?

Paradigm #2 – Career based

So maybe you have 2 of the 3 qualifications, but you want to build a “sustainable” career in GEM? Think of fellowship as a jumpstart to that career: putting in the time at the outset to reap rewards at the end (much like medical school). By completing a fellowship, you are telling those that you work with that you have both the expertise and desire to be successful in this field. This can sometimes be difficult to communicate to people who don’t know you or who are selecting between many qualified candidates for a position. In addition, the advanced degree that you gain from fellowship will lend you another layer of legitimacy. Some examples of careers that will benefit you by doing a fellowship are:

- Academic Careers in Emergency Medicine: Do you want to become faculty in an emergency department that actually earns part of his or her living from creating international opportunities? Fellowship directors, international directors, jobs with protected time for international projects; these jobs are few and far between, and are almost exclusively offered to individuals that have completed fellowship.

- International Organizations: If you want to become a medical director, research director, or be part of the leadership in an international organization, NGO, or the UN, a fellowship can take you a long way.

- Niche/Expert: If you are looking for a niche in this large field of emergency medicine and you want to be able to speak with authority on your topic of choice, then a fellowship gives you the skills and credentials to do so.

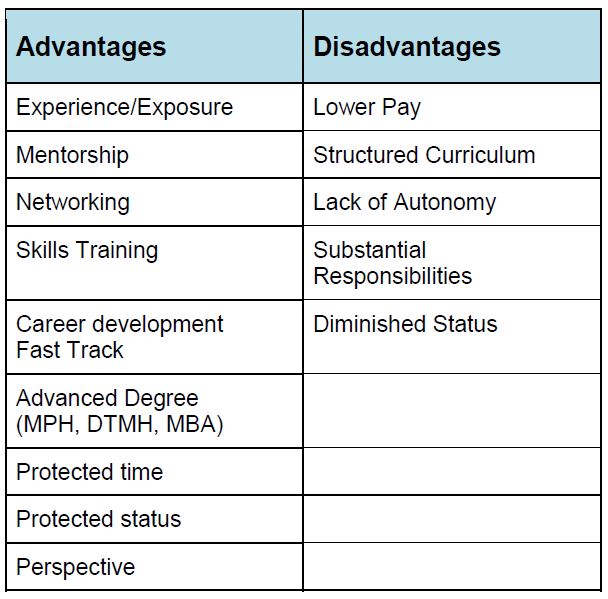

What other advantages does a Fellowship give me?

According to over half of the fellowship directors in the country, the most common advantages are the ones addressed in the above paradigms – experience, mentorship, training, and career development. However, there were other ones that were often mentioned.

- Protected time: In fellowship you have the time to go to conferences, time to complete research, to meet people, and to gain further education.

- Protected status: Many of the leaders in the field remember what it was like to be without experience, and many times will go out of their way to help you with projects, land interviews, and score grants. They want to see you succeed so that you can advance the field.

- Perspective: Fellowship also provides you with a different perspective on healthcare. Normally you approach health care from an individual place. However fellowship allows you to care for populations rather than just individuals.

Are there any disadvantages?

According to the directors, there are also disadvantages of doing a fellowship.

- Less Money: Firstly and most obviously, as a fellow you don’t make an attending’s salary, much less the same salary that you would make as a community doc. In fact it could be up to 1/3 of what some faculty make.

- Expertise Limitations: In addition, a program may not have expertise in every aspect of GEM, and they may not be able to offer you training in all of the aspects of GEM.

- Lack of Autonomy: If you have a structured fellowship curriculum, you may not have the autonomy to become exposed to all aspects of GEM that you are interested in. More on this later.

- Program Responsibilities: You will also have substantial program responsibilities while in fellowship, which can at times be difficult to balance.

- Decreased Status: Some directors also cited the fact that as a fellow, some attendings may still see you as something other than a peer. This perception of decreased status can be frustrating as well as possibly hinder you when trying to work alongside certain people.

Should I go straight in from residency?

This is a very common question that is asked of fellowship directors. When is the best time to do a fellowship? Is it right out of residency when you are still in learning mode, or is it after a couple of years when you have more experience? From those that we interviewed, there were many different opinions on this. To illustrate this take a look at this conversation between “Straight Through” and “Wait a Couple of Years”.

- Wait - Do I really have to go straight through? I want to gain more experience and come into fellowship with much more to offer and a better idea of what I want to focus on in fellowship.

- Straight - I see what you’re saying. However the truth is, the longer you wait the harder it is to go back. For a number of reasons (salary, responsibilities, autonomy) once you are in the “real world”, it is much harder to go back to being a fellow. In addition, life gets in the way sometimes – you get married, have children, and gain more responsibilities as you get older and this can place fellowship lower on your list of priorities. Why not get the training while you are still primed for it?

- Wait - Yes but I’m not sure what I want to do yet! I can’t just go into fellowship if I don’t know what I want to do yet!

- Straight - Fellowship can help you to design your career path going forward and give you a better idea of what is available once you graduate. In addition, you will have access to already established, large-scale projects headed by potentially great mentors that have your interests at heart.

- Wait - Yes, but what if my interests don’t line up with the fellowship’s plans? I don’t want to get roped into a project that I can’t get behind.

- Straight - Hopefully you have done your homework on which fellowships have the same goals as you do, and these are the ones that you are applying to.

- Wait - But I have this great interest in setting up a residency program in Peru. I have contacts there that are on board, and I think that I want to explore this first before going into fellowship.

- Straight - There are lots of different types of fellowship programs out there (you will see in the next section.) There are many that will support whatever you are passionate about. In addition, you will likely make more progress and impact with experienced people backing you. That being said, if you have an amazing goal that you want to do on your own, then you may want to complete that before you start fellowship. The last thing fellowships want is someone who isn’t committed. The problem with taking years off is that it can be perceived as non-committal. If you are going to wait for fellowship, make sure that you can articulate why you waited – both for yourself and for the fellowship program. One last thought: If you already know exactly what you want to do and don’t need a fellowship for it, do you need to do a fellowship at all?

- Wait - Okay, I understand. So what I give up in autonomy, I gain in experience and mentorship? Okay this is something that I will have to think about, but I am much more comfortable with knowing more about it.

Remember that each of the decisions that we have talked about are very personal decisions, and no one can tell you what you want. All we can do is try and guide you into the best possible informed decisions. Remember to keep this in mind as you continue to read.

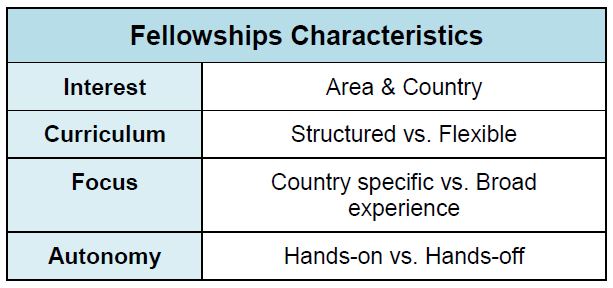

What do I look for in a fellowship?

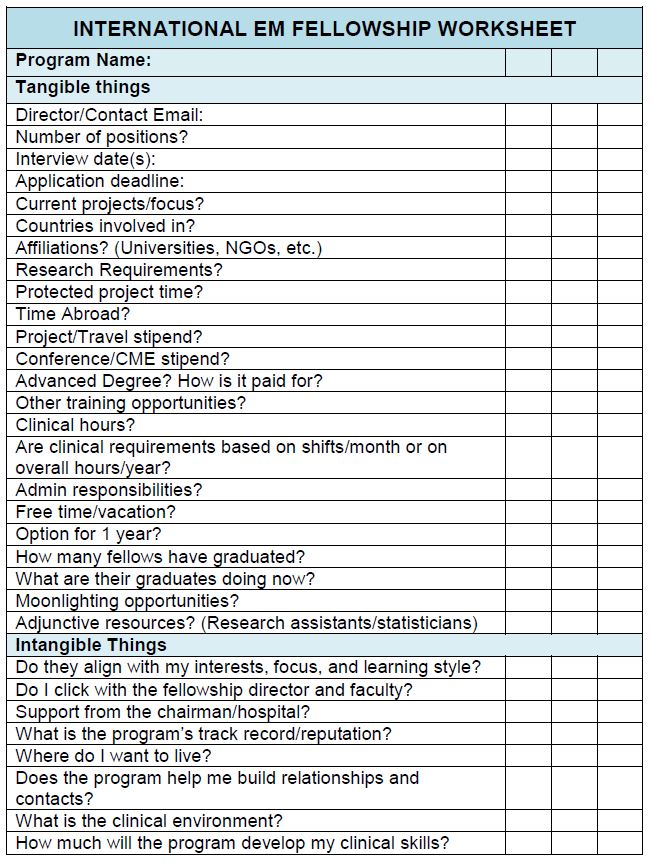

This is very important. Fellowships will impart on you the training and perspective that you will carry with you for the rest of your career. Because this is a non-boarded fellowship, programs are very heterogeneous and lack standardization. This can be a strength or weakness depending on who you talk to (more on that later). Given that there is no board exam at the end, you need to find a fellowship that gives you the tools to make your career successful. Applicants are as different as the fellowship programs, and career success will be measured differently for each person. Seek to find the best fit for you and don’t concentrate on things that, in the end, don’t mean as much.

The most unanimously agreed-upon attribute of a good program was support. You want a program that supports you and your goals, and it should offer the keys to making this a reality. Support comes from many different levels in the hierarchy of a fellowship program: from the hospital administration towards the department, the chair towards the fellowship, the core fellowship faculty for the fellows, and the fellows for the residents. However the most important person to have support from is the fellowship director. Your director should be able to take time to mentor you and work with you, instead of leaving you to fend for yourself. He or she should encourage you and hold you accountable to your goals. A director that is too busy to dedicate time to you will be detrimental

That being said, every program has different internal interests and strengths. It isn’t fair to try and change a program’s entire structure just because they aren’t interested in what you are. This is a big field, and you should find out what YOU need before trying to decide on the fellowship that is right for you. A program with the best fit will likely be much better than a program with a big name or lots of credentials.

Look at what the people in the fellowship are doing and talk to current and former fellows - will it give you opportunities that you want? To explore this, we will break down the differences in programs into interests, curriculum, focus, and autonomy. We will also talk about other considerations that you will need to make.

Interests (Areas of Interest)

The first and likely the second most important aspect to consider after support is whether your interests and the program’s match. What do they focus on? What are they good at? In general, programs tend to focus on one or more of the 3 areas of interest (AOIs) mentioned earlier – EM development, public health/capacity building, or humanitarian/disaster relief. In addition different programs have different regions/countries of interest. You don’t want to be working on humanitarian relief if you’re interested in EM program development. You don’t want to be in India if your heart lies in Myanmar. One of these may be more important than the other, but your interests should align with at least one, and this should shape how you consider the rest of these attributes.

Curriculum (Structured vs. Flexible)

Another important aspect to consider is the type of curriculum it offers. Programs tend towards being either structured or flexible, however most are somewhere in the middle of this continuum. Structured programs have a set curriculum that all fellows follow, because it is believed that there are core concepts that all fellows need to learn despite what their interest is. Some structured programs tend to glean this curriculum from some form of the “7 Core Competencies” referred to earlier, but this is not universal. Other programs believe that they should allow the fellow to determine what they want to learn and focus on. Most programs fall somewhere on the spectrum between these two ideas. Different applicants will gravitate towards different types of programs. Some applicants appreciate the structure, and others find this structure stifling. You need to match your style of learning to the program’s style of teaching.

Focus (Broad vs. Narrow)

Some programs will have one area of focus, and others have many. This applies to both the program’s areas of interest and the countries that they are involved in. You will have to decide which you prefer, by deciding if your goals match up to the program’s focus. Are you interested in a specific AOI or country or are you open to new opportunities? Maybe your AOI is specific but your country is flexible, or vice versa. For those without specific goals, then it may be better to be at a program that has a wide focus. Keep in mind that a program can be structured but still have a broad focus in both their countries and areas of interest.

Autonomy (Hands-on vs. Hands-off)

Some programs are very involved in every aspect of their fellows’ journey. This ensures that the fellow remains engaged and on task. While most directors agreed that being hands-on is much preferable to hands-off, some fellows value a large degree of autonomy when working and can feel stifled by hands-on programs. These fellows tend to be proactive, self-starting, and independent, however they are also at risk of getting side-tracked and off task if left alone too much. Remember that 2 years can pass quickly and you want to have something to show for it.

Other Considerations

These are other things that were consistently mentioned during our conversations with the fellowship directors.

Personality: To directors, this was more important than any of the characteristics listed above. You will be working very closely with your program for up to 2 years, and possibly longer. How do you approach problems? How do you resolve conflict? How do you interact with those of differing opinions? Although no one personality is right or wrong, differences in personality between the program and the fellow can make working together more difficult. Fellowship interviews are good for this. If you don’t mesh well with the people you interview with, then likely that program isn’t the best place for you.

Research: While “research” has different meanings to different people, most programs place at least some emphasis on publishing your work. That being said, there are differences in the amount of emphasis. In addition, different programs will have different types of projects. Take a look at the amount and type of projects that former and current fellows/faculty are involved in and this will give you a better idea of how you will fit in.

Time Abroad: How much do you want to be out of the country? Will the program allow you to stay abroad long enough to make your project/research worthwhile? This will be answered on an individual and project basis, however if you are only allowed very limited time abroad this could be a drawback. On the other side, what if you have a family that you can’t leave? Are you expected to be abroad 6 months of the year? How flexible is the program on this?

Advanced degrees: The vast majority of fellowships today have the option of obtaining an advanced degree, most commonly an MPH. Given the lack of a standardized board exam, this is the one of the unifying factors of fellowship training. It is almost universally agreed upon that each program offers some form of advanced degree, be it MPH or other degree, and that this degree be global health focused.

Other Training: Many programs offer other types of training in addition to a full advanced degree. These are universally agreed to be helpful, but the importance of these differ among directors. Courses such as the H.E.L.P. course, DTMH, and other training mentioned earlier in this book can be great additions to your training and should be considered.

Length of program: Most directors surveyed believed that most programs should be 2 years, unless the fellow already has an advanced degree. One year is a very short amount of time to get anything done. If the fellow already has a degree, the consensus was that exceptions can be made.

Experience: There were differing opinions on this. On the one hand, some directors thought that older, more established programs are better. The idea is that they have a better idea about the day-to-day operations of a fellowship, more contacts, more available funds, and more field/research experience. However others felt that older programs could be rigid and less open to the fellow’s individual needs or to new ideas. These latter directors felt that newer programs can be more accommodating and innovative because they are not set in their ways. Again, the applicant will have to make their own decisions about what they prefer.

Contacts: In the words of one director “the point of fellowship is to make contacts, and to have someone that will prevent you from making the same mistakes that they made. Unfortunately (for the first point) people are not interchangeable, the important people are the important people, and certain people and organizations are keys to doing what you want in life”. Does the program help you build the relationships and contacts that will help you achieve your goals?

Affiliations: It was noted that many programs have affiliations with universities and medical schools overseas, international NGOs (MSF, IMC, ICRC, WHO), and governments that can help you achieve your goals. With few exceptions these can be immensely valuable, especially if you hope to work with one of these entities in the future.

Other skillsets: Many programs or individual faculty members may have expertise in a subject that can prove invaluable depending on your interests. These will vary according to program, however a few of the skillsets that were mentioned were: tropical medicine, ultrasound, pediatrics, EMS, medical informatics, statistics/epidemiology, public policy, or education. This should be taken into consideration as well.

Questions to ask

Some of these questions may seem like minutia, but we were assured by many directors that these can greatly affect your fellowship experience and these are things that are often overlooked by many applicants.

How is the fellowship paid for? Between your salary, travel funding, stipends, and advanced degree expenses someone has to pay for it. It is important to make sure that the funding stream for your fellowship will be secure. Most have at least some combination of the following.

- Clinical shifts - This is the way that the majority of the fellowships are funded. You aren’t making a full working wage, so the money that comes in as a result of your clinical work will go towards keeping the fellowship open. The proportion of the fellowship that is funded in this manner will be based on many different local factors.

- Endowment/grant - Some fellowships are partially paid for through an endowment or from a grant to the program. While this can mean that you will be taking home more of your hard-earned cash, these endowments are only as good as long as the money stays in place. This is almost never a problem, but is something to keep in mind.

How is my advanced degree paid for?

- Fellow - The money is taken out of your salary. This isn’t as bad as it sounds, because it is all pre-tax money so the degree will still be much cheaper than if you went out and tried to pay for it yourself.

- Program - This takes no money out from your salary to pay for it. This is obviously preferable, but may or may not be a deal-breaker for you and should also be weighed against how much your base salary is.

How many clinical hours am I working?

- This is measured in “full time equivalents” (FTEs) which is normally calculated based on a 40-hour work week, so 0.5 FTE would be 20 hours/week. As one director said: “Don’t let them turn you into a workhorse for cheap labor. This still happens and is a problem”. How are you supposed to conduct meaningful projects or earn your degree if you are always in the ED?

- In addition to this, it is important to know whether your hours will be averaged over the entirety of the fellowship or month-to-month? This will determine how flexible your schedule is to adapt to your needs.

Where will I be working? This is your day-to-day life, so make sure it is something that you can live with.

- What is the clinical environment like?

- Is it a clinically-strong ED?

- Is it academic or community?

- What kind of support do I have?

- Will I get to (or have to) work with residents?

What about my time?

- How much administrative work will I be doing?

- How much free time/vacation will I have?

- How much time will I have abroad?

What about money?

- What is the starting salary?

- Keep in mind that the starting salary isn’t always the most important factor in determining how much you are getting “paid”. Consider stipends, hours worked, and how your advanced degree is paid for.

- Do you get travel stipends?

- Do you get project stipends? What can they be used for?

- Remember that the fellowship may only provide funding for “already established projects” which means that it may not be applicable to the project that you are planning.

What are your people doing?

- What percentage of the faculty still work in global health?

- Are you going to be mentored by someone who last left the country in 1983?

- Are the former fellows in positions that allowed them to pursue their passions?

Am I allowed to do 1 year if I already have a degree?

- This will differ from program to program.

What other resources are available? This can make your fellowship much more productive if you don’t have to spend your time doing things that detract from your learning.

- Do I have access to a statistician that can help with number crunching?

- Can I get a research assistant to help me with data collection?

- Do I have the support from a division of global health?

- This goes back to the “support” that we spoke about earlier.

Pearls from individual directors

- “When trying to gauge programs look at how prolific a program is. Do they regularly contribute to the body of literature? Are they involved with national or international conferences? Are they helping make decisions? Do they have a presence overseas? Are they helping to shape the world, or sitting in the background?”

- “You have to take into account where you want to live as well. No one operates in a bubble, and the happiness of your family and those around you is just as important as the program’s individual attributes.”

- “Ask yourself how much is this program going to develop my skills as an emergency physician and clinician? Global Emergency Medicine is not just about research and program development, you are still learning how to be a doctor and that has to be taken into account.”

- “Be weary of programmatic dogma in their approach to global health. Are they open to new ideas? Your training will dictate to some extent the way you approach global health and those that work within it.”

- "It is important to find a fellowship that can expose you to at least four of the seven core competencies, but also allow and support you to focus a bit more if you need to. For example, some fellows want to develop skills in humanitarian assistance, disaster response or direct clinical service delivery; while others might be looking for a longer term exposure...applicable public health methods, or acute care health systems strengthening. If you have prior international experience and are more monomaniacal in your focus, your fellowship should have the capacity to help you hone that specific area of interest."

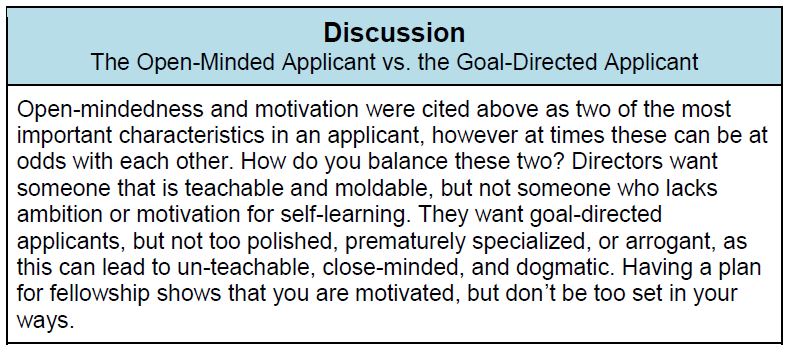

What do fellowships look for in the applicant?

Bottom line: There is no perfect candidate. Every program is different and is looking for different things. The only universal response that we received was that every program is looking for the “best fit” for their program. However what this meant was always different. These are the other characteristics that our fellowship directors found important. For the most part they are listed from most commonly to least commonly mentioned.

Core Characteristics

These were universally agreed upon by our group of directors.

Passionate: The second most important characteristic mentioned, after being the “best fit”, was that they wanted applicants with a passion for GEM. They wanted what some described as “lifers”: applicants who were committed to the specialty and wanted to improve it and make it

grow. Programs want to see that you are already involved in GEM. What are you doing to show that? Are you working on international/global health projects? Are you up to date on current issues? Do you understand the contexts that are involved and where you will likely fit within the world of GEM? Do you have an idea of what your interests are? You don’t have to have answers to all of these questions, but you do need to be able to show that you have thought about them. The directors often talked about those applicants that don’t know what they want to do but they felt like “travelling may be fun”. Don’t be this applicant.

Motivated: The next most common response was that they wanted an applicant that was motivated and internally driven. While many programs go to great lengths to support and guide their fellows, directors pointed out that fellowship will likely be the most free time that you have in your life and you need to use it wisely to make an impact. In short, they want leaders. Do you create opportunities for yourself? Do you get yourself involved, or do you wait to have someone involve you? It was mentioned that this is often a characteristic found in applicants coming from residencies that lack a strong international infrastructure.

Open Minded/Adaptable: Programs are looking for people that are adaptable, enthusiastic, and open-minded. There will be many situations during fellowship and life that are unpredictable and don’t work out as planned, and a successful fellow needs to be flexible enough to adapt to these situations and move on. A high-maintenance fellow was one of the most commonly cited negative traits from the directors. This is where the interview is really important – this tells them a lot about who you are and is very hard to demonstrate on a paper application.

Specific topics

International Experience: Previous international experience in residency can go a long way to showing interest in the field, but it isn’t absolutely necessary. Passion is much more important to fellowship directors than experience. Fellowship directors understand that international experiences are hard to obtain in residency, especially if your residency program is not involved internationally. “Experience” can be obtained in fellowship; passion is not teachable. Directors want to see a wide variety of experiences rather than many international trips. That being said, if you have limited international experience, it is important to have other ways to show your commitment to GEM. Examples of these are:

- Away rotations – doesn’t necessarily have to be international. These show that you can operate in environments that aren’t your own.

- Participation in projects – especially those that show that you have been preparing for GEM. Such as those in public health, resource-poor settings, or tropical medicine (see chapter 9).

- Residency tracks or interest groups - not all residencies have these, but if yours doesn’t then consider starting your own.

- Local interest groups – there are lots of interest groups centered on global health all over the country. They don’t necessarily have to be within the residency.

Publications/Research: Publications can be one of the best ways to show innovation, research skills, and commitment to the specialty. That being said, experience and passion are more important to directors than publications. Much more important is to get involved in some type of project, whether that be research or not.

Educational Experience: Remember that a large part of GEM is teaching others how to do something. This can be as simple as giving lectures to students and junior residents, or as complex as helping to develop a residency curriculum in Kazakhstan. If you have given lectures, please place them somewhere on your CV. This is one of the best ways to show that you have this skill. That being said, directors noted it as important but not paramount to an application.

Foreign languages: Again, shows passion (especially if it is the language of your country of interest that you didn’t learn growing up) but this is not essential.

Will this ever be a boarded specialty?

This was the last topic that we discussed with each of the directors and has been a topic of discussion since fellowships first started. There are several ACGME accredited specialties in Emergency Medicine, and with accreditation came greater standardization and board examinations. It was almost universally agreed upon by those we spoke with that GEM will not be a boarded specialty in the near future. While some directors lamented the lack of perceived legitimacy inherent in this fact, the majority saw this as a point of pride. The reasons cited were varied, but there were some consistencies. Many felt that this is simply just too broad of a specialty to confine within parameters that can be tested with a board exam. It was thought that trying to do this would detract from the original reasons for starting fellowships in the first place: to give the fellows the tools to achieve their goals. Many also thought that the advanced degree offered by fellowships was a surrogate way of standardizing fellowships. As discussed earlier, however, keep in mind that due to the lack of formal standardization, just because you completed a fellowship doesn’t mean that you will be offered THE job or THE position that you desire. You should focus on learning as much as you can in fellowship and take advantage of the opportunities given to you by virtue of you being in one of these fellowships. This makes it that much more important to pick the right one for you.

Of note, the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine has a program to “approve” fellowships that meet a list of standards. The process is designed to create quality control for EM fellowships that are unlikely to become ACGME-approved. International EM fellowships were recently allowed to apply for this process. It is optional for fellowships to apply to this process, but the document describing the requirements to achieve approval is comprehensive and is a good starting place for candidates who are interested in comparing the features of different programs.

- Approved IEM fellowships: http://www.saem.org/membership/services/fellowship-directory?Fellowship_Type=Global+International+Emergency+Medicine

- Approval Criteria: http://www.saem.org/docs/default-source/fellowship-approval/global-em-fellowships/saem-fellowship-approval-process--application-and-program-description-for-global-em-fellowship-programs-final-version-for-board-of-directors-1dec14.doc?sfvrsn=6

How do I apply?

You still with us? If you decide that IEM Fellowship is right for you, you can find information and the application requirements for each program on the International Emergency Medicine Fellowship Consortium (IEMFC) website www.iemfellowships.com. The IEMFC is a new organization of fellowship directors and former directors that help to unite all of the fellowships under one roof. This website was launched in 2013 and has been a wonderful resource not only for applying, but also for finding “stats” on specific programs. All of your application materials will be uploaded via this site, with a few exceptions that are clearly marked on the site. For the most part, application materials include a cover letter, CV, three letters of recommendations, a personal statement, and your USMLE scores (and sometimes a transcript.) If you are selected, you will be invited for an

interview. As for competitiveness of programs, this can vary widely. The bottom line for applications is this: there are normally more fellowship spots than there are applicants, so if you absolutely want to go to fellowship, there will be a spot for you somewhere. That being said, some of the more established programs can be VERY competitive as most of the applicants in the country have likely applied to them. In addition just because you can get a spot, doesn’t mean that it will coincide with your interests. Keep this in mind.

Timeline (subject to change year-to-year, but this is a good overview)

- Spring/Summer before senior year: spend time researching programs on both their own websites and the consortium website, and narrow down your list of programs that you are interested in.

- September: most of the application deadlines are in mid-September. This will require you to get ALL of your materials in by that time. Leave yourself plenty of time for that last LOR to be sent.

- October: Interviews are usually clustered around ACEP, as this is the most convenient time to get everyone in the same place. It may help to schedule an easy elective at this time to prevent scheduling problems.

- November: This is not a match. The “no offer date” is the 2nd Monday of November, after all of the interviews have been completed. On this date you will be called and offered a spot. You have 24 hours to accept or reject your position before it goes to another candidate. All of the programs have agreed not to extend any offers before this time, and most recently there were no reports of any program violating this. PLEASE RESPOND PROMPTLY SO THAT THE PROGRAMS CAN CONTACT THE NEXT PERSON ON THEIR LIST. Think about how nervous you were on “match” day and imagine what that next applicant will be feeling like waiting on an offer.

The Application

- Cover Letter: Some of you may have never written a cover letter before, and it is pretty straightforward. However, don’t overlook this. As one author puts it: “the cover letter is the trailer, and your CV is the movie”. There is a great short introduction on how to write these written by Dr. Bill Sullivan for post-doc applications but it is just as applicable to fellowship applications2. The only deviation we have is that this should probably be kept to 1 page, not 1½.

- Curriculum Vitae: This is how you show directors that you have the qualities that they are looking for. There are so many different ways to do this that we won’t try and tell you which format to use. However, keep in mind that fellowship directors have to read tons of these so the ease of reading and how it looks on paper is almost as important as the content. PLEASE HAVE SOMEONE PROOFREAD IT!

- Letters of Recommendation: These are important because they can demonstrate that you have the qualities discussed in this section. Most programs want you to have three, and many programs would like to see each of the following mentioned in at least one of your letters: clinical skills, research experience, teaching experience, and service experience.

- Personal Statement: This is less important than the CV and the LORs, however this is also much less tangible. This is how the program gets to know you before they meet you and is also your way to explain any deficiencies in your CV or things that you don’t get to mention in your CV that make you the excellent applicant that you are.

What about the interview day?

Most interviews happen around the time of ACEP during your final year of residency. This interview is much like all interviews; the program wants a chance to meet you and see what makes you tick. The interview dates tend to be more flexible than residency interviews. Interviews may happen at the location of the fellowship, or at another location that is convenient for both the interviewer and interviewee (some of them happen at ACEP!) This is a great opportunity to find out more about the program’s personality. You will almost definitely meet with the fellowship director, but other than that it will depend on where you are interviewing. If interviewing at the hospital, you may also interview with the chairman (who actually has to sign off on your “hiring”), and other high-level faculty. Other activities may include touring the school of public health, ED, and other support facilities.

Tips from the interview trail (From those that just did it)

- When making your final year schedule remember that you will need time to interview. Requesting an elective, vacation, or less time-intensive rotation during the time of ACEP will make scheduling interviews much easier and less stressful.

- Get to know the other applicants that you are interviewing with. These will be colleagues for the rest of your life. It goes without saying that you should be collegial with them. Don’t be a gunner - that’s not what this specialty is about.

- Remember that the most important thing to a program is a good “fit.” Just because a program has a big name doesn’t mean that they will be able to give you what you need, and vice versa.

What should I be doing in the meantime?

Find out what you’re interested in! Your fellowship will frame the rest of your life. Determining your interests will help you narrow down the programs that you want to apply to, the projects that you will become involved with, and what you will focus on. Begin to cultivate the skills and traits talked about above. It is never too early to start, plus the longer you have been involved with the specialty, the more it will show in your application. Put yourself in a position to meet people involved in GEM. Go to conferences, read the literature, and get involved as a resident or medical student.

Are there other places to get information on a program?

Websites for programs are notoriously out of date and often reflect what is currently happening at a program. If you want to know what the program is up to, look at what the fellows are doing. They may be the most active parts of the program and can be a great barometer of what is happening there. Look where they are working and what they are doing. Look on PubMed to see publications from the faculty. Current and former fellows also tend to me much more available than the fellowship director for questions or inquiries, and will be much more likely to give you unfiltered answers to your questions. Another helpful avenue is to look at what the core international faculty are involved in – you don’t want to apply to a fellowship hoping to do EM specialty development only to find out that they only work in humanitarian relief!

References

- Bayram J, Rosborough S, Bartels S, Lis J, VanRooyen MJ, Kapur GB, Anderson PD. Core curricular elements for fellowship training in international emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2010 Jul;17(7):748-57.

- Sullivan, Bill. How to Write a Killer Cover Letter for a Postdoctoral Application. ASBMB Today. Oct 2013. http://www.asbmb.org/asbmbtoday/asbmbtoday_article.aspx?id=48927